Synopses

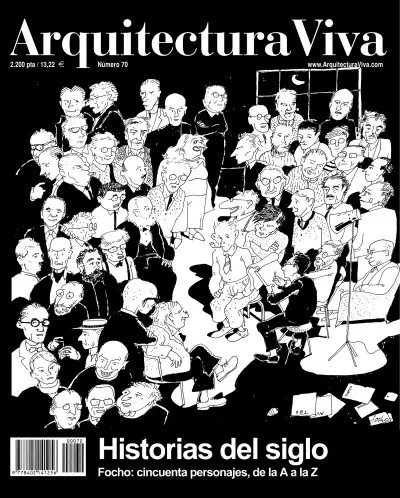

Strips of Our Times. The turn of the century and millennium tempts us to look back, and we have succumbed here through a sure hand and a conspiratorial glance. Justo Isasi was a comics fan and an amateur cartoonist before he became an architect, a design teacher at the Madrid school, or a founding member and regular feature writer of AV and Arquitectura Viva. Like Louis Hellman alias Hellman or Gustav Peichl alias Ironimus, Justo Isasi alias Focho is an architect who draws architectural cartoons. In 1991 the magazine started up a section in which Focho associates a well-known architect with a famous cartoon character. The first strips had Norman Foster and Tintin racing in a jeep toward a launching pad in the shape of the Hong Kong Bank, which would send to the moon a rocket resembling the Collserola Tower; or Peter Eisenman and Little Nemo lost inside an inverted Wexner Center; or James Stirling and Alice in Wonderland taking a scolding by the Queen.

Many other consecrated figures have since then appeared with fictitious paper heroes: by chronological coincidence, such as in 1995 – the year that celebrated the centenary of the movies – when old Frank Lloyd Wright of FaIlingwater fame played opposite Walt Disney’s beautiful Snow White, history’s first animated feature film which was premiered, like the house, in 1937; by expressive affinity, such as that which paired the Galician master Alejandro de la Sota to the Rumanian Saul Steinberg, thanks to a shared ironic and distanced vision, refined sensibility and constant search for expressive intensity with minimal means; or even by ideological proximity, such as that which brought on the love affair of a melancholic Italian, Aldo Rossi, with the liberated leftist Valentina of Guido Crepax in Venice’s Lido.

More than a half-hundred Focho strips have seen print since the birth of the section, some dedicated to historic personages whose stature as masters is unquestionable, and others to contemporary figures who have been or are in the current limelight. The result of the selection here is a fresco in which fifty big names of architecture meet fifty cartoon heroes, in a game that replaces built realities and persons of flesh and blood with drawn fictions and imaginary personalities. Notwithstanding attempts to come up with a balanced cast of architects through a few eliminations and additions, we have maintained the original tendency to give more attention to Spanish and Latin American architects. Hence the likes of Antoni Gaudí Eduardo Torroja, José Luis Sert; José Antonio Coderch, Miguel Fisac and Alejandro de la Sota appear with Carlos Raúl Villanueva, Luis Barragán or Óscar Niemeyer, not to mention Rafael Moneo, Ricardo Bofill, Santiago Calatrava, Enric Miralles and the Portuguese Alvaro Siza, whom Spain a] most considers one of its own.

For a better understanding and enjoyment of the strip cartoons, these come with explanations of their genesis, where Focho mixes personal recollections and opinions with references that will enable one to situate the cartoonists and their creatures in their own contexts. And in counterpoint to fantasy is a selection of works by the fifty real-life architects, as well as fifty relevant quotes from like number of historians and critics. As much as possible, with few exceptions, the buildings that appear in the strips reappear in the complementary true-life graphic summary. Finally, our choice of authors for the extracts (Bruno Zevi on Mendelsohn, Stanislaus von Moos on Le Corbusier or Vincent Scully on Kahn) followed a single criterion: expertise on the period or figure concerned. As in the case of the architects, all those selected deserve to be here, although the selection could not include all those deserving.

Contents

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976)

Tadao Ando (1941)

Erik Gunnar Asplund (1885-1940)

Luis Barragán (1902-1998)

Ricardo Bofill (1939)

Santiago Calatrava, (1951)

José Aantonio Coderch (1913-1984)

Peter Eisenman (1932)

Miguel Fisac (1913)

Norman Foster (1935)

Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983)

Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926)

Frank Gehry (1929)

Walter Gropius (1883-1969)

Zaha Hadid (1950)

Herzog y de Meuron, (1950)

Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971)

Philip Johnson (1906)

Louis Kahn (1901-1974)

Rem Koolhaas (1944)

Le Corbusier (1887-1965)

Adolf Loos (1870-1933)

Richard Meier (1934)

Konstantín Mélnikov (1890-1974)

Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953)

Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969)

Enric Miralles (1955)

Rafael Moneo (1937)

Richard Neutra (1892-1970)

Óscar Niemeyer (1907)

Jean Nouvel (1945)

Renzo Piano (1937)

Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964)

Richard Rogers (1933)

Aldo Rossi (1931-1997)

Eero Saarinen (1910-1961)

José Luis Sert (1902-1983)

Álvaro Siza (1933)

Alejandro de la Sota (1913-1996)

James Stirling (1926-1992)

Kenzo Tange (1913)

Vladímir Tatlin (1885-1953)

Giuseppe Terragni (1904-1941)

Eduardo Torroja (1899-1961)

Jørn Utzon (1918)

Aldo van Eyck (1918-1999)

Robert Venturi (1925)

Carlos Raúl Villanueva (1900-1975)

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959)

Peter Zumthor (1943)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Strips of our times

This terrible century clamors for amnesty, more than homage. Amnesty means amnesia, because only anesthetic oblivion can heal the open wounds in the body of a humankind that has seen atrocious catastrophes. And what homage can we give to a century that has put scientific progress at the service of industrialized extermination, and where the fragile fruits of prosperity and liberty nourish an evergrowing gap between the opulence of the free and the misery of the subjected? The advance of knowledge and the spread of freedom have had their dark reverse in the multitude of victims left behind by a shaken century, the close of which now calls for penitence, more than jubilation.

Hebrew tradition marked the sabbatical year with a remission of offences and dues, and the Christian orb took from this to institute its own jubilees. But besides the forgiving of sins and debts, the land was allowed to rest so that it might renew itself. As Jacques Le Goff suggests, the turn of the century and millennium may present an opportunity for pardon, as well as for the beginning of “a new youth for the world”: a time of rebirth for a humanity that has multiplied its numbers and divided its certainties, urbanized the planet and thrown its fragile living crust off balance, effected the modern revolution and partaken of its happy and sour fruits.

With the century coming to an end, our jubilee pause evades both contrition and assessment, and tries instead to brighten up its glum countenance through a hundred friendly figures; fifty architects and fifty cartoon heroes linking up their biographies and works to sketch a smiling portrait of a hundred harsh years. Humor is sometimes more caustic than condemnation, but Focho’s pencil saves his characters from abrasive criticism. Rejuvenated by his generous gaze, the protagonists of the century inhabit these pages with a mischievous irreverence that does not exclude the occasional irruption of skepticism or melancholy: irony protects us from the fake bubbles and sharp edges of the world without hiding the scars of knowledge.

There is no choral canon to be found in this kaleidoscopic rejoicing. The alphabetical criterion leads from Aalto to Zumthor and chronology engenders a Catalan string that stretches from Gaud( to Miralles, while geographic dispersion has made Hispanics take priority over the European nations that spearheaded the Modern Movement, as well as over those who made the 20th an American century. Many will miss Wagner Sullivan or Berlage; others might demand the presence of Van de Velde, Behrens or Perret; and some will search in vain for Taut, Oud or Scharoun. But this rowdy gathering has been more charitable to recent figures than to old masters, forgetting perhaps that the youth of architecture that the jubilee claims often feeds on the past.