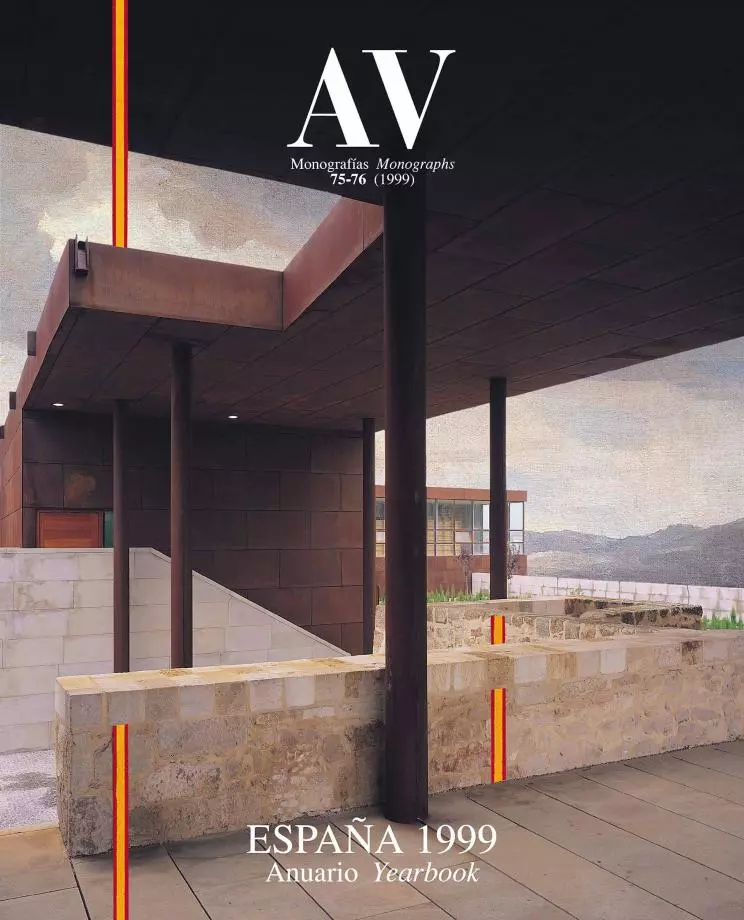

Montehermoso Civic Center, Vitoria

Roberto Ercilla Miguel Ángel Campo Juan Adrián Bueno- Type Culture / Leisure Civic center Refurbishment

- Material Wood Stone

- Date 1993 - 1997

- City Vitoria

- Country Spain

- Photograph César San Millán

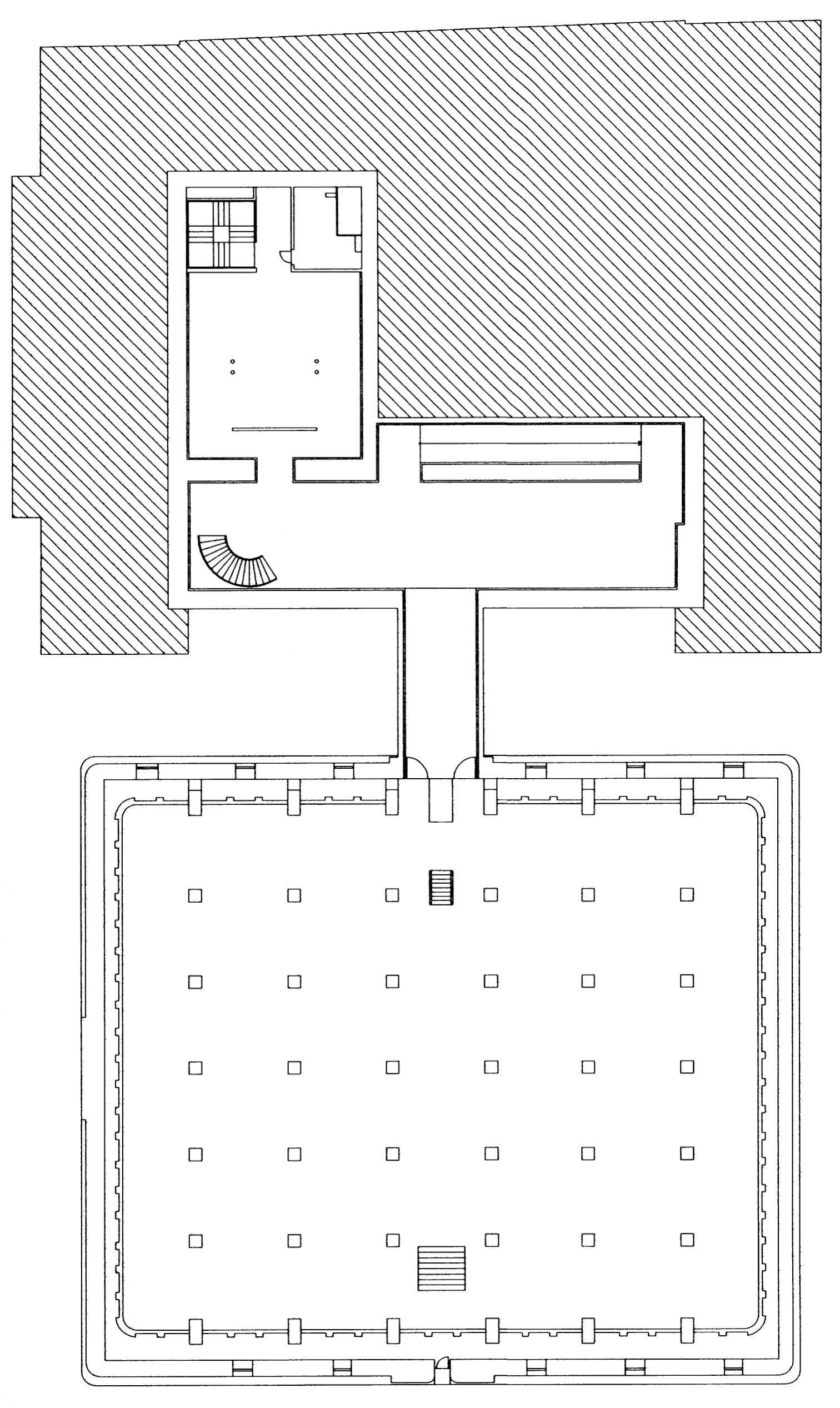

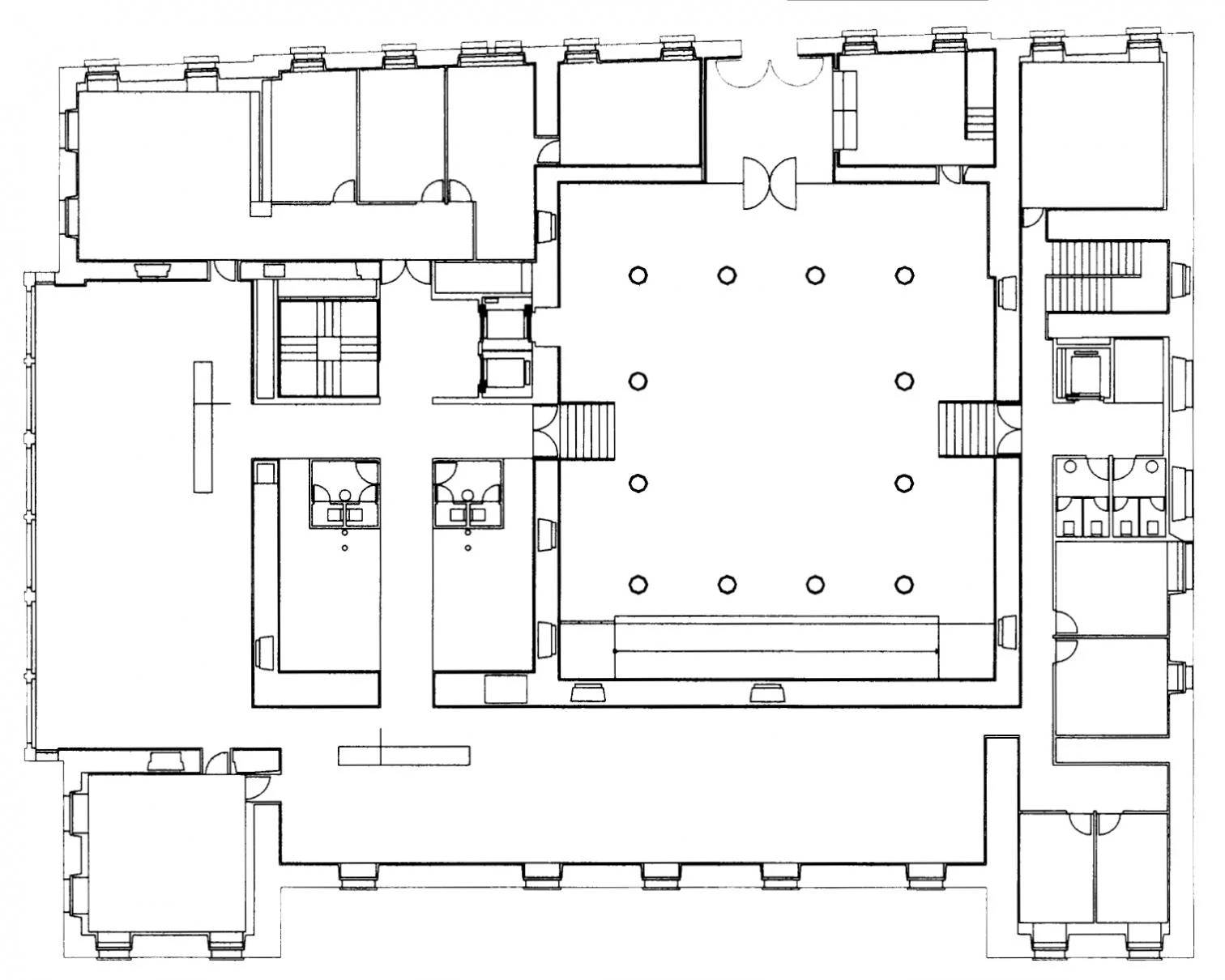

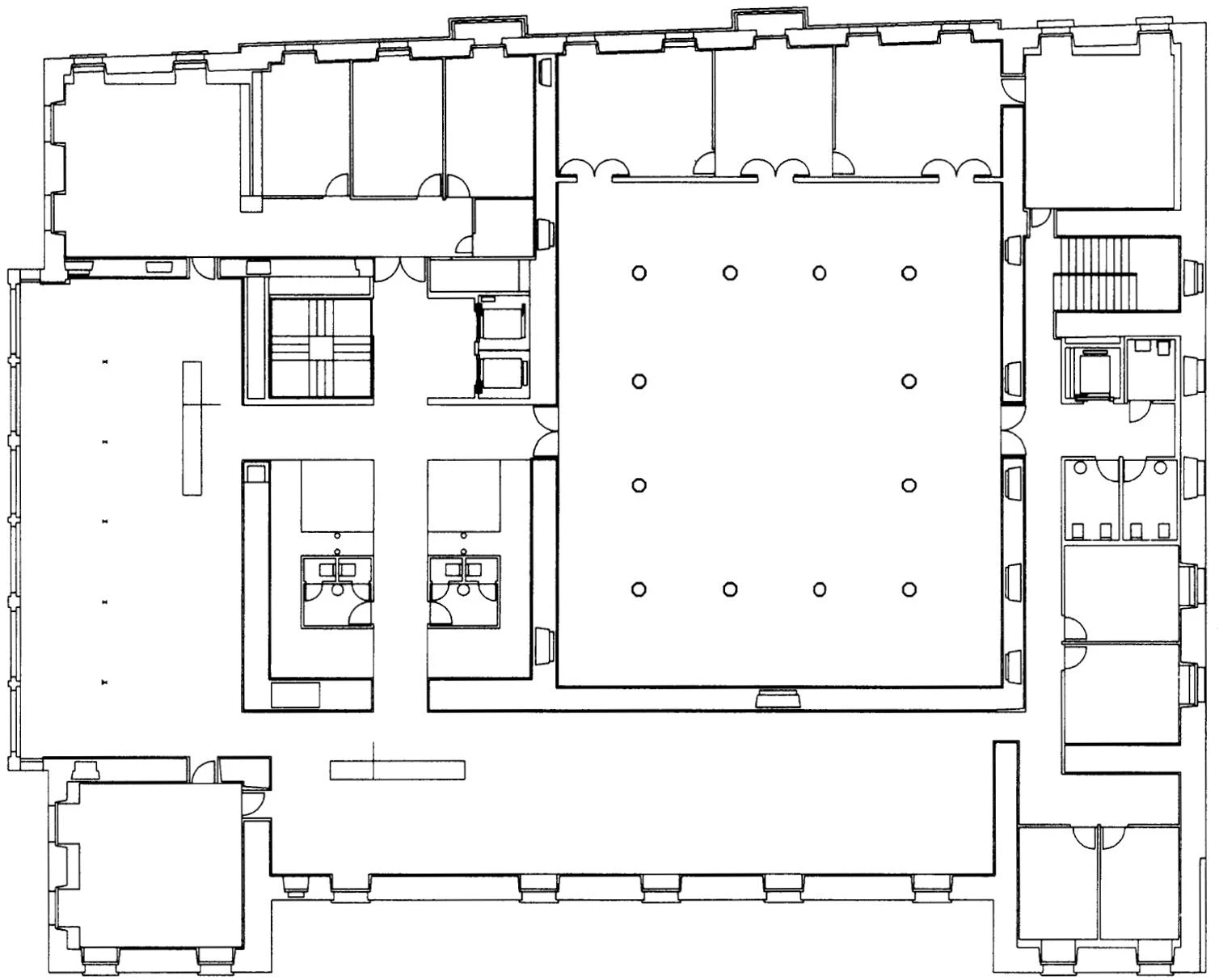

The intervention rehabilitates the old palace of Montehermoso for use as a cultural center, recuperates an adjacent old water tank, connects this subterraneously to the rest of the premises, and renovates an adjoining garden. The building dates back to the 16th century, and has undergone numerous transformations in the past. In 1877 it became an episcopal residence, and this was when its most valuable elements were destroyed. The original construction was organized around a cloister whose perimetral spaces formed a nearperfect square, but such a balanced distribution was upset when an extension was carried out toward the south, shifting the gravitational center in that direction, away from the vertical void that generated the old perimetral routes.

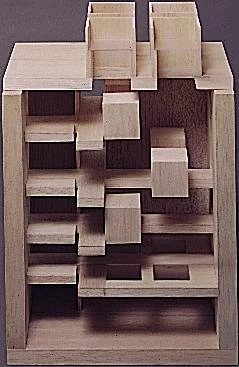

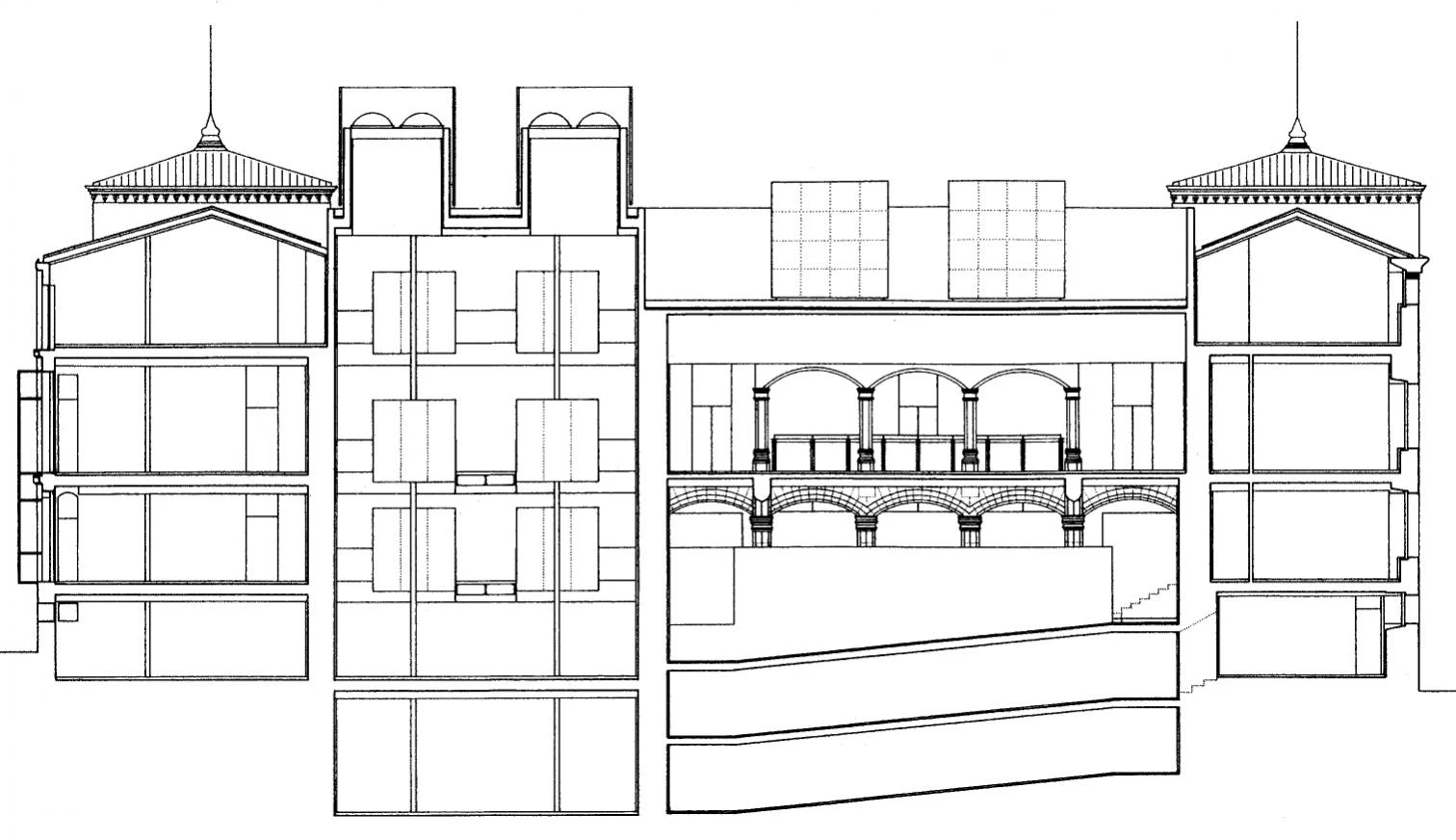

On the southern side of the cloister a covered courtyard has been created at the full height of the palace, where wooden cubes floating in space, hold the lavatories for the center or create skylights in the roof.

The cultural center is conceived as a place for civic action, one where the visitor is not a mere observer but a part of the activities housed within. Out of respect for the collective memory of the city, the solution adopted does not ignore the preexisting. The typological scheme of the cloister is recovered, and repeated in the form of a contiguous courtyard that rises the entire height of the building. It is here that new architecture is introduced. Besides the vertical communication system and the building services, a series of wooden cubes float in this void, attached to two vertical guides which appear dislocated on plan. The cloister and this new court are each lit by eight cubic skylights. In the case of the intervention, these are roof projections of the lavatory cubicles.

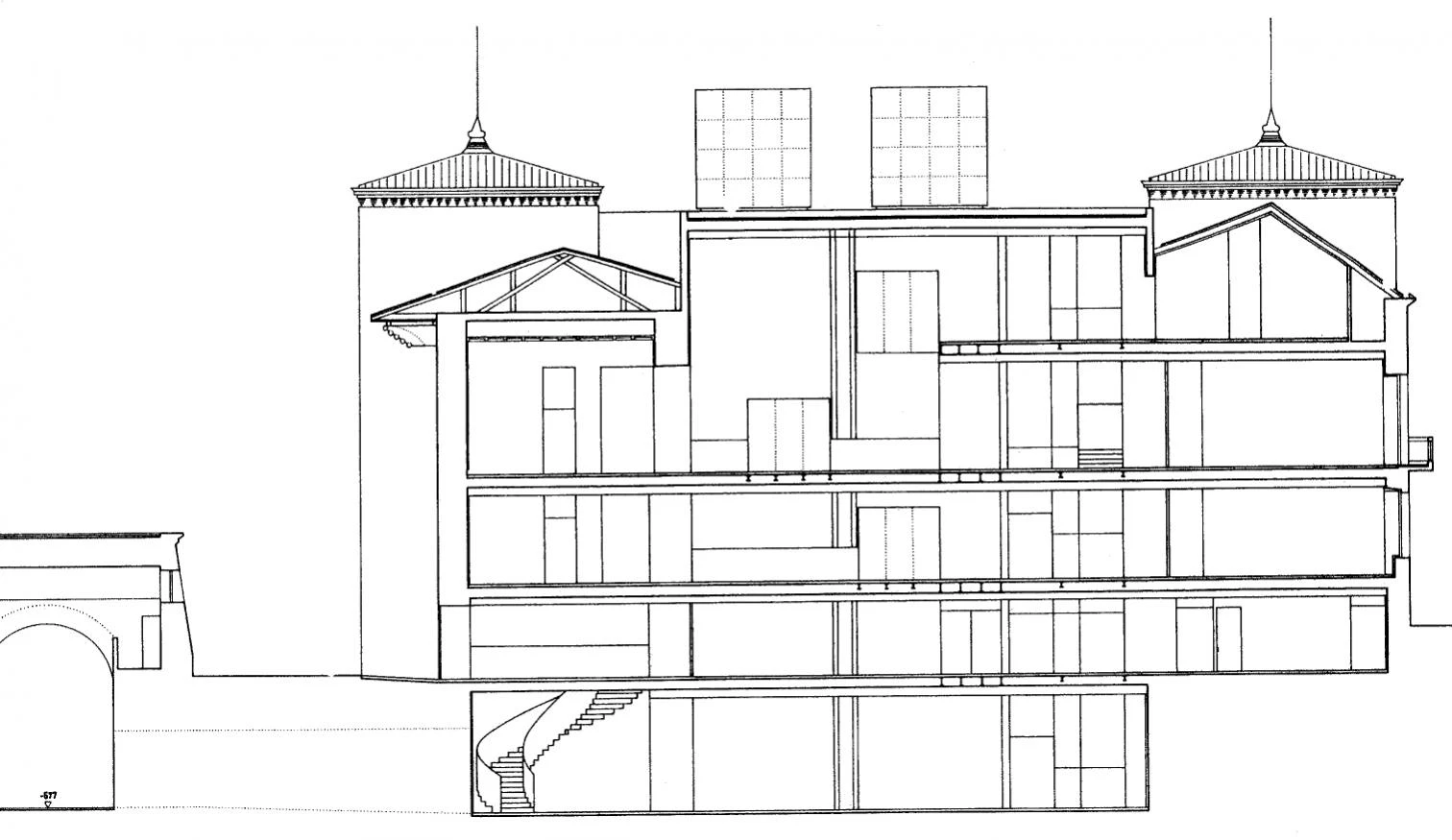

The water tank becomes an exhibition hall, connected with the main building under the road. In the network of pillars, the differing tones of the stone demonstrate the tide marks, where the water has reached in the past.

Inside the building, the walls of the rooms are finished stuccowork and stone, and the resulting clean, brightness is enhanced by a careful handling of light. On the outside, the intervention can be appreciated in the latticework that shields the southern facade, in the deliberately intricate eloboration of the window frames, and in the skylights, which are clearly cut out in the building’s profile. The disused water tank has been converted into a temporary exhibition gallery. To arrive at the gallery, one has to follow a path under the Calle Mayor. The visitor descends either a curving staircase or a doublespan ramp supported by the wall, after traversing a small, low opening. This is the threshold through which one crosses into an underground world of penumbra, where changes in the tonality of the stone of the columns show the tide marks where the water has risen to in times gone by, and silently exude the changes of the passage of time.

The old episcopal palace, built with stone materials, contrasts sharply with the steel, wood and glass employed in this new intervention, in the form of inserted pieces of furniture.

Cliente Client

Ayuntamiento de Vitoria

Arquitectos Architects

Roberto Ercilla, Miguel Ángel Campo, Juan Adrián Bueno

Colaboradores Collaborators

Eduardo Tabuenca (arquitecto architect); Javier Valdivieso, Javier García, Íñigo Hierro (aparejador quantity surveyor)

Consultor Consultant

Eduardo Martín (estructura structure)

Contratista Contractor

Lain

Fotos Photos

César San Millán