Memory speaks in these ten interviews with masters. I borrow from Vladimir Nabokov’s autobiography the title for the presentation of these conversations, transcribed as monologues to place the focus on the protagonists, whose voices I hope to have reflected faithfully. The texts are arranged by the age of the speaker, from the most veteran – Frank Gehry, born in 1929 – to the youngest – Bjarke Ingels, in 1974, almost half a century later –, and in all cases except these two the dialogue was organized as a biographical itinerary, from family origins and school years to the latest projects. This effort to encompass the whole career of the architect permits illustrating the most characteristic works of each one, and this graphic structure is maintained even in the two interviews – the first and the last – where, as mentioned, the biographical scheme was not applied or is somehow blurred.

The interviews have been carried out in recent years, most in the context of the arquia/maestros program, with two exceptions: again Gehry, with whom I met in Bilbao in 1997, when the Guggenheim was about to be completed; and the dialogue with Luis Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón, which took place at the Barcelona Pavilion in 2007, coinciding with their Mies Award. Luis passed away five years later – his disappearance is the only one we have to lament when publishing these texts – and hearing his voice again causes piercing pain. Some of the conversations were recorded at a studio in Barcelona, but others took place in spaces related to the architects – Peter Eisenman at Santiago’s City of Culture, Norman Foster at his Madrid foundation, Renzo Piano at his Punta Nave studio –, and Jacques Herzog’s was the only public event, held at the Fundación March.

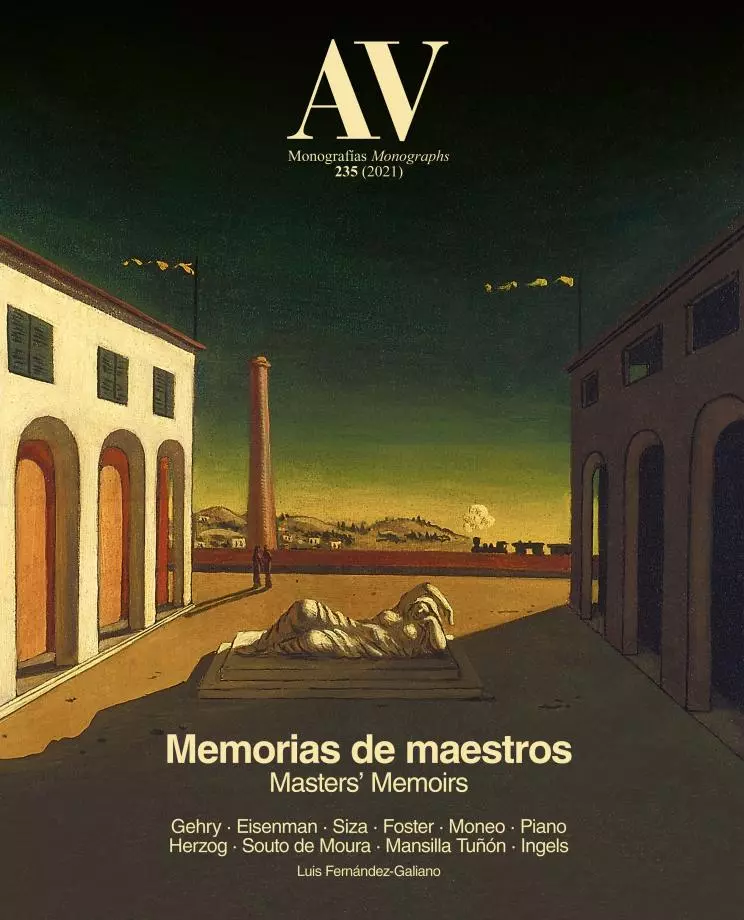

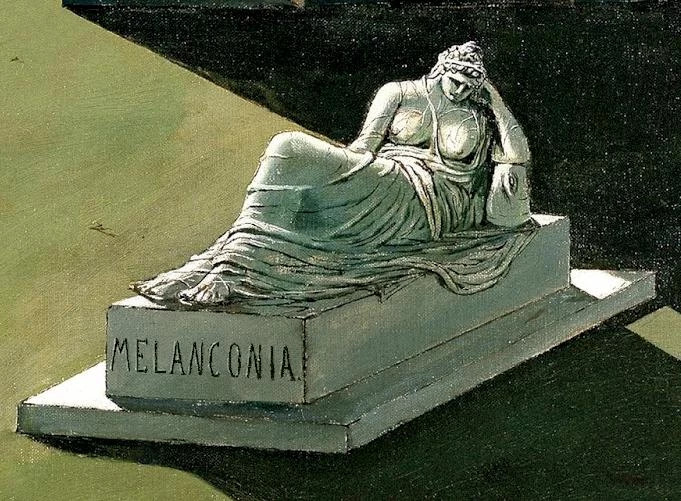

Besides the above-mentioned, which include two Americans and four Europeans (British, Italian, Swiss, and Danish), the list of interviewees features three Iberian masters – Álvaro Siza, Rafael Moneo, and Eduardo Souto de Moura – so the selection is reasonably representative, even though some key names are missed. The conversations were carried out indistinctly in either Spanish or English, and are featured here in the two languages. Making memory speak undoubtedly carries a melancholic component, and both the cover image – which uses a canvas dated by De Chirico in 1916 but painted in 1944 – and the mythical Dürer engraving opposite this page – Melencolia I of 1514 – share title, which can also be read on the base of the same reclining figure from another work by the metaphysical Italian painter. Melancholic, introspective, and analytical, memory speaks on these pages. Listen to it.