The week the newspaper El País was born, the last of the modern masters died. Alvar Aalto passed away on 11May 1976, closing for architecture an era of heroes and certainties. The old pioneer Frank Lloyd Wright had gone in 1959; Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, the two great coeval founders of the modern canon, died in 1965 and 1969 respectively; and the severe Louis Kahn disappeared in 1974. Architecture thus began the final quarter of the 20th century orphaned of masters and abundant in perplexities.

Two books, both of them published in 1966, had called into question modern orthodoxy: Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, challenging the minimalist and disornamented discipline of the modern, put forward the linguistic variety and formal contrasts befitting a plural society, and made its author, Robert Venturi, the leading architectural exponent of America’s liberal populism; while The Architecture of the City, questioning the tabula rasa of modern invention, defended the grounding of buildings on the logic of urban fabrics, turning the Milanese Aldo Rossi into the most notorious representative of Europe’s leftist rationalism.

Each on one side of the Atlantic, the two architects and professors had planted a time bomb in the conceptual foundations of modernity, and the controlled demolition of that edifice of convictions would be heard through the decades to come, which witnessed the continued conflict between the heirs of the modern creed and a pleiad of heretics inclined to replace their dogmas with other intellectual and artistic fidelities.

The convulsed and fragmented landscape of the past twenty five years is summed up here through five images that try to tighten the threads of the debate in knots of meaning, and which in all cases reproduce museum projects; that is, not only the most characteristic buildings of recent architecture, but also those best expressing the at once exhibitionistic and reflective nature of a time that simultaneously promotes spectacle and memory.

1977: A Happy Machine

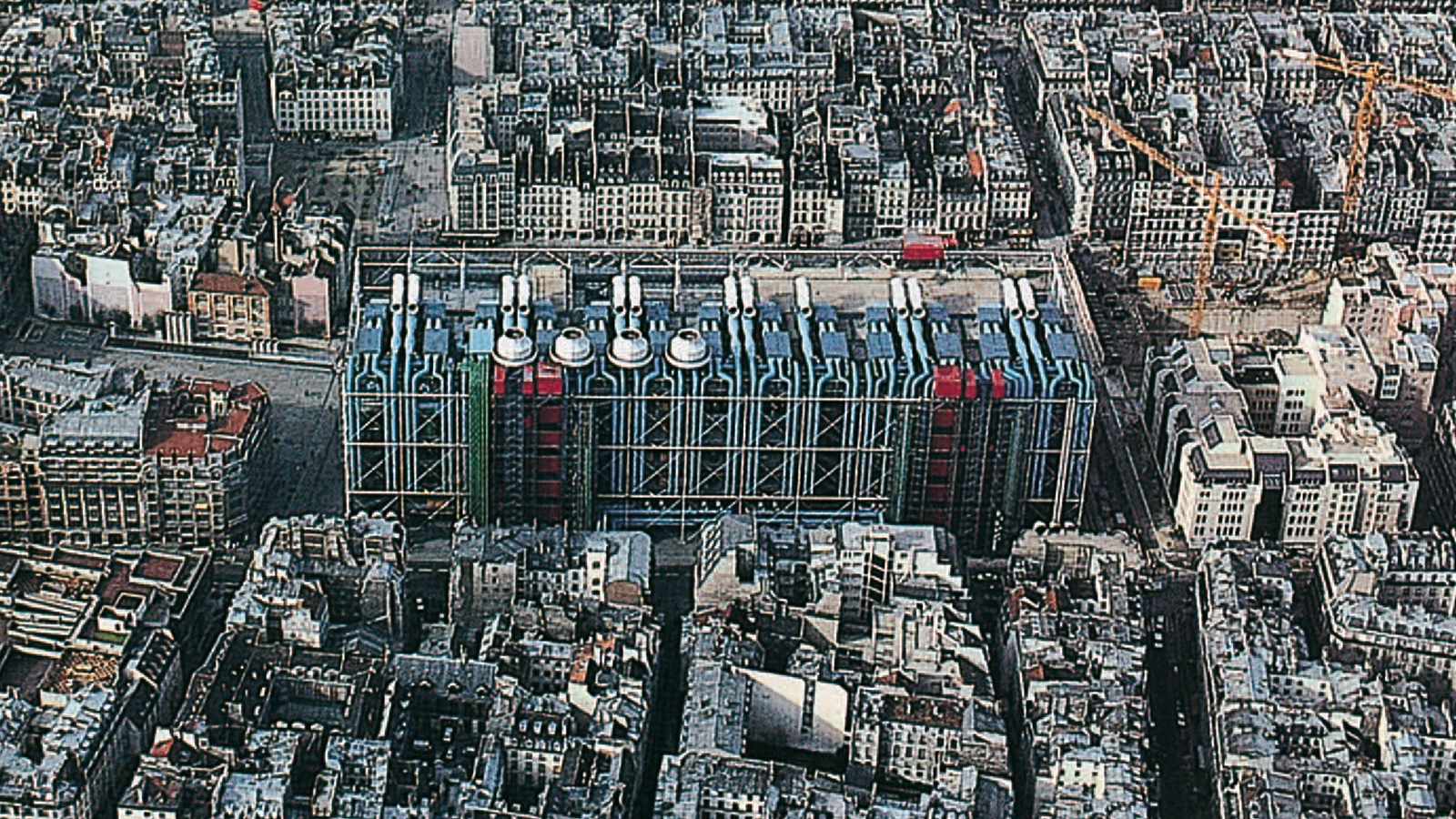

The first illustration is of the Pompidou Center raising its coloristic industrial structure in the dense tapestry of the Parisian Marais quarter. It remains a modern building in its devotion to technology and indifference to context, but its playful, accessible look flirts with the most amiable variant of pop, and its determined demystification of art manifests the counterculture sensibilities of ‘68. This ideological crucible was the work of two long-haired, casually dressed architects who won the 1971 competition to their own surprise, and finished their defiant, happy machine in 1977 to general scandal. The Italian Renzo Piano and the British Richard Rogers, later champions of hightech, were then populist apostles of a ludic and interactive brand of engineering that was to reap huge success among critics and the public, but whose carefreewaste of material and energy would be censured by the oil crises of 1974 and 1979.

The Centre Pompidou of Paris, finished in 1977 by Piano and Rogers, is still modern in its technical optimism and ignorance of urban context, but its playful attitude reflects the countercultural spirit of the year ’68.

Economic cooling gave these years theright climate for the laconic return to order advocated by Rossi, whose programmatic Gallaratese housing development was completed in Milan in 1976, and for the ironic traditionalism preached by Venturi, consecrated as a unanimous fashion when the same Philip Johnson who had introduced modernity into the United States in 1932 decreed the eclosion of postmodernity in 1979, holding up the model of his classicist skyscraper for ATT from the cover of Time. The eighties would hence be postmodern, and in contrast to the critical overtones of this term in the realm of social sciences, in architecture it would be dressed with the loquacious forms of a decidedly conservative classicism, often in tune with the political mutations introduced from the Anglosaxon word by Thatcher and Reagan – despite architects’attempts to nuance the hierarchical nature of the classical order through the cultural filter of skeptical distortion expressed by the ephemeral facades of the Strada Nuova in the 1980 Venice Biennale.

1983: Ironic Classicism

Such is the context of the second image, which shows the Staatsgalerie of Stuttgart, a project initiated when the Pompidou first opened its doors and completed in 1983, with the postmodern decade in full swing. Its author, the British James Stirling, had been trained in the modern discipline, attaining extraordinary notoriety in the sixties through buildings of functionalist expressivity, but a stint in his studio of the Luxembourg architect Leon Krier converted him to classicism in 1970, and his subsequent works display a smiling historicism that deforms conventions with unexpected humor, culminating in the Stuttgart museum: a festive amalgam of Schinkel and Le Corbusier where half-buried columns, arches and stone cornices are juxtaposed with grotesquely oversized rails and canopies painted pink, sky blue and apple green, the result a mannerist complex sprinkled with citations that reconciles the ironic with the picturesque.

Landmark of postmodern counterrevolution, finished by James Stirling in 1983, the Stuttgart Staatsgalerie is a festive mix of Schinkel and Le Corbusier that distorts historic traditions and conventions with irony and humor.

The postmodern counter-revolution would find a particularly fertile humus in American commercial developments, for which classicist figuration provided an at once socially efficient and culturally legitimate language with architects like Charles Moore or Michael Graves. It was to entrench itself in this niche for a long time, and be exported to Europe, where it would come in tune with the most rhetorical versions of traditionalist monumentalism, grandiloquently represented by the French urban developments of the Catalan Ricardo Bofill. Nevertheless, under the deluge of postmodern historicism, the old technological modernity would stubbornly survive, even if sometimes by exchanging its abstract roughness for the expressive baroque of exposed structures such as that of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, an Asian skyscraper by the British Norman Foster that was finished in 1985, shortly after the Stuttgart museum.

1986: A Timeless Work

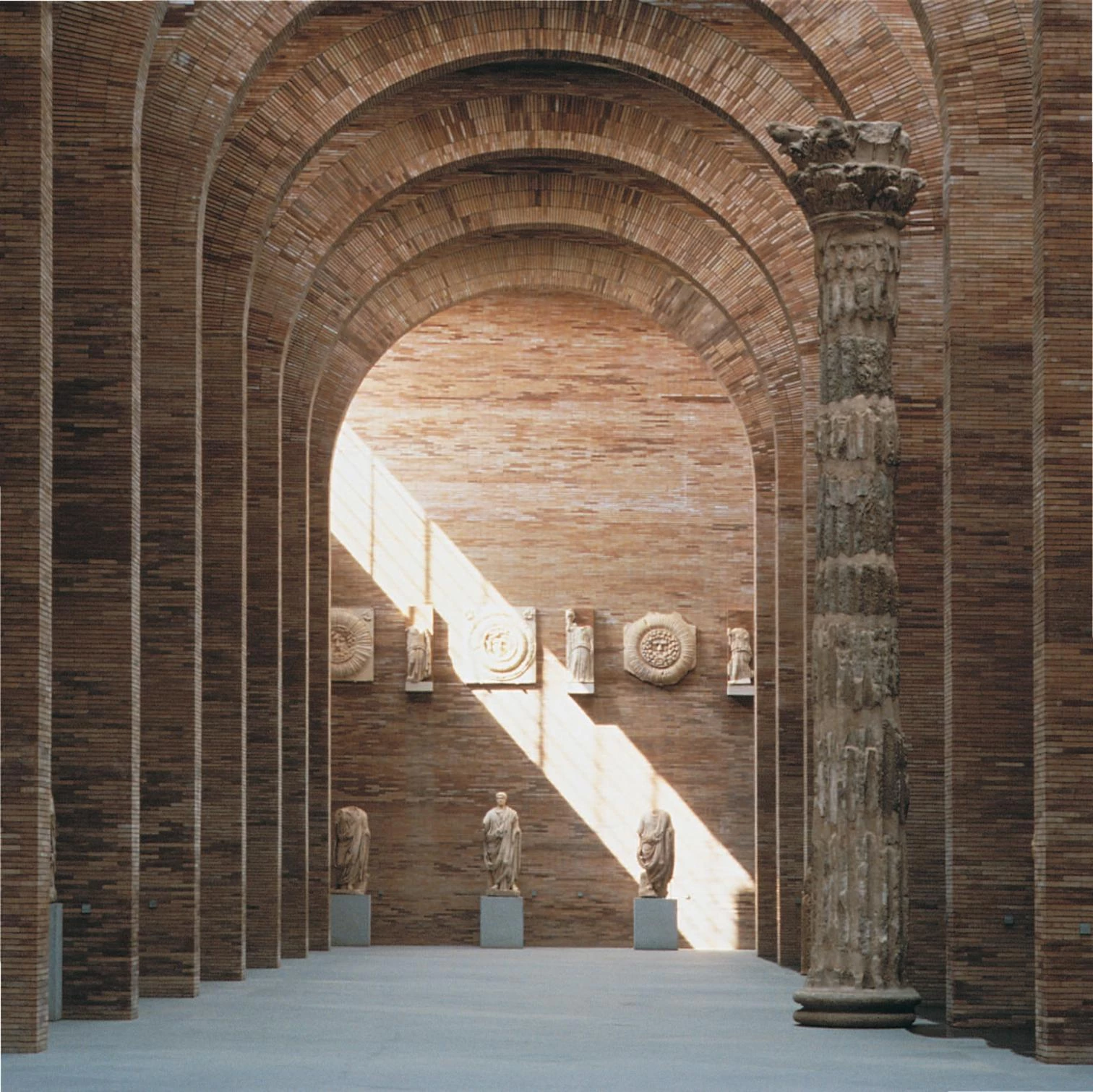

The next year saw the opening of the building shown in the third illustration, the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida by Rafael Moneo, who reconciled Rossi’s urban lessons with Venturi’s figurative disinhibition to erect a work of rare perfection: effortlessly implanted in the site, rigorous in its geometric precision and loquacious in its perspective frontality, the museum is at once succinct and imposing, vernacular and Roman, modern and postmodern. The tactile gravity of the brick masonry combines with the violent light of the clerestories to mold interiors that are both severe and weightless, monumental in their formidable scale and familiar in their predictable textures. It was not the swansong of contemporary classicism, but from then on, playful traditionalism would have to measure up its smiling ironies to the lyrical syncretism of Mérida.

The Roman Art Museum of Mérida, completed by Rafael Moneo in 1986, joins Rossi’s urban ideas and Venturi’s figurative proposals, but distances itself from the most literal and mannered versions of the classical revival.

In Paris, the grands projets endeavored to marry modern abstraction with classical monumentality through geometry. From Ieoh Ming Pei’s pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre to Johann Otto von Spreckelsen’s perforated cube at La Défense, the French presidential rhetoric derived from Rome the same lesson as Le Corbusier: the monumental city is built with elemental shapes. And in London,Venturi himself used his skeptical allusive language to extend the National Gallery: in a metropolis subjected to the esthetic dictatorship of a traditionalist prince, the reticent classicism of theAmerican made it possible to reach a compromise between abrasive modernity and thematic facsimile. But none of these syntheses would be attained with the same happy, timeless naturalness of Moneo’s Mérida museum.

1989: Fractures of History

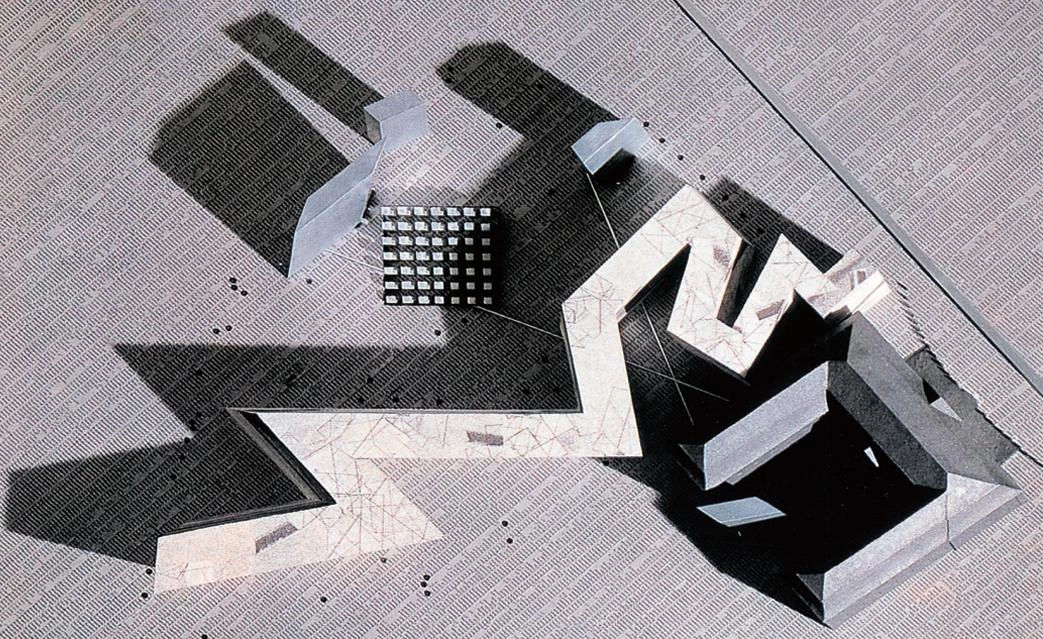

The nineties would bring other preoccupations, and our fourth image sums up with vigorous eloquence the fractured spirit of the period that followed the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. A New York exhibit organized by the ineffable Philip Johnson in 1988 had premonitorily promoted the unstable, catastrophic forms coined deconstructivist as the best expression of shaken times, and the Polish-American Daniel Libeskind’s project for Berlin’s Jewish Museum the following year admirably crystallized those ruptures of history in the emblematic city of the transition. Completion would take a decade, but unlike the other constructions cited here, the actual building would not match the dazzling impact of the model that zigzags with the abrupt and discontinuous energy of a convulsed century.

Immediately after its completion in 1997, the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum by Frank Gehry joined the collection of contemporary icons, and its agitated, warped forms replaced fractured ones to symbolize uncertain times.

Prosperous and perplexing, the nineties saw the heyday of Asia’s Pacific Rim expressed in a colossal flowering of skyscrapers and airports, the latter including those built on manmade islands in Osaka and Hong Kong; the economic dynamism of America materialized in a unanimous sprawl of manicured urban developments and thematic commercial centers; and the propitious moment of a Europe committed to its political integration made manifest in a rejuvenation of old urban cultures, a movement best exemplified by Barcelona, which managed to blend the geometric laconicism of modernity with the tenacious layers of history, reconciling memory and spectacle in a seamless combination.

1997: Time of Storms

By happy chance, this spectacular architecture would erect its most celebrated milestone in another Spanish city, Bilbao, whose Guggenheim Museum appears in the fifth and last illustration. The Californian Frank Gehry’s titanium building, finished in 1997, instantly joined the collection of icons of the contemporary world, and its stormy forms became the symbol of times shaken by technological and social change. The last five years of the 20th century thus saw edges giving way to warps, in a shifting from fractures to the formless that has inevitably served as metaphor for a historical period of uncertainty.

Immediately after its completion in 1997, the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum by Frank Gehry joined the collection of contemporary icons, and its agitated, warped forms replaced fractured ones to symbolize uncertain times.

These material and esthetic mutations found their most disturbing interpreters in the young Dutch architects gathered around the provocative, surreal projects of Rem Koolhaas, and their most stubbornly resistant trenches in those Swiss professionals faithful to the demanding artistic discipline of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. The result is a fertile dialogue between Rotterdam and Basel that nourishes with ideas and forms the most stimulating debates of the day. Maybe as a sheer consequence of contemporary globalization, but also perhaps as a sign of the Iberian Peninsula’s receptive permeability, both Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron begin the 21st century with major works in Portugal and Spain, becoming part of an architectural scene that has taken in all the currents of the moment, from the cracked topographies of the New Yorker Peter Eisenman to the immaterial futurism of the French Jean Nouvel: plural voices added to a landscape already in possession of a broad gamut of languages, from the Portuguese Álvaro Siza’s poetic abstraction to the Valencian Santiago Calatrava’s sculptural engineering, which makes this soil a generous laboratory of experiments at the threshold of a century orphaned of certainties.