Threshold of Light and Shade

Formal Dilemmas, from Stockholnm to New York.

At the threshold of another year, light and shade blend uncertainly. Several implacable centenaries will reel off revisions and nostalgias, mixing up Empire and Disaster in the simultaneous commemoration of Philip II and the Generation of 98, and reconciling fire and snow in the parallel tributes to Federico García Lorca and Alvar Aalto. The patriotic celebrations will revive a Spanish melancholy which is already rearing its head in the skirmishes of history or language, and the artistic homages will engage south and north in a dialogue during a year that is also to feature the Lisbon Expo and Stockholm’s turn as European culture capital. But the great currents that shape the world flow in the economic subsoil, and this colossal arena will in the next few months see a confrontation between euro hopes and Asian unknowns: the challenge and risks of planetary integration. The global economy is a physical reality and an intellectual construction. Architecture is too both material and symbolic, its formal oscillations expressing the ambiguity of a time when a tendency toward the universal meets with the resistance of the singular, and when the splendor of spectacle coexists with the dark tenacity of memory.

In Stockholm, Rafael Moneo has opted for serenity: the pyramidal skylights of the Museum of Modern Art draw a picturesque and friendly figure in the horizontal panorama of the island of Skeppsholmen.

Last year closed festively with the titanic pyrotechnics of Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, to a critical and public acclaim that exceeded the most optimistic predictions of the Basques, whereas this year began with the sound serenity of Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art, its inauguration on St. Valentine’s Day putting a start to the activities lined up for the Scandinavian city’s shift as cultural capital. The chasm between the explosive forms of the Californian Frank Gehry and the sober volumes of the Navarrese Rafael Moneo is more than a matter of sensibility or language; these art museums are exemplary and extreme expressions of two opposed attitudes which each simultaneously invoke a collective spirit and the individuality of the architect: on one hand the effort to form part of the global culture of spectacle, and on the other the temptation to seek shelter in the familiar landscapes of memory. Institutions and cities must choose between din and silence, and architects try to adjust the volume of their works to the sound of the times and the echo of places, alternating screams and whispers, as Moneo himself does: here the dazzling and hermetic Kursaal of San Sebastián, two colossal, translucent and slanted prisms whose frame has already been erected on the edge of the Urumea River, and there the murmur in halflight of the Stockholm museum, whose pyramidal skylights cut a picturesque and friendly figure in the horizontal panorama of Skeppsholmen Island.

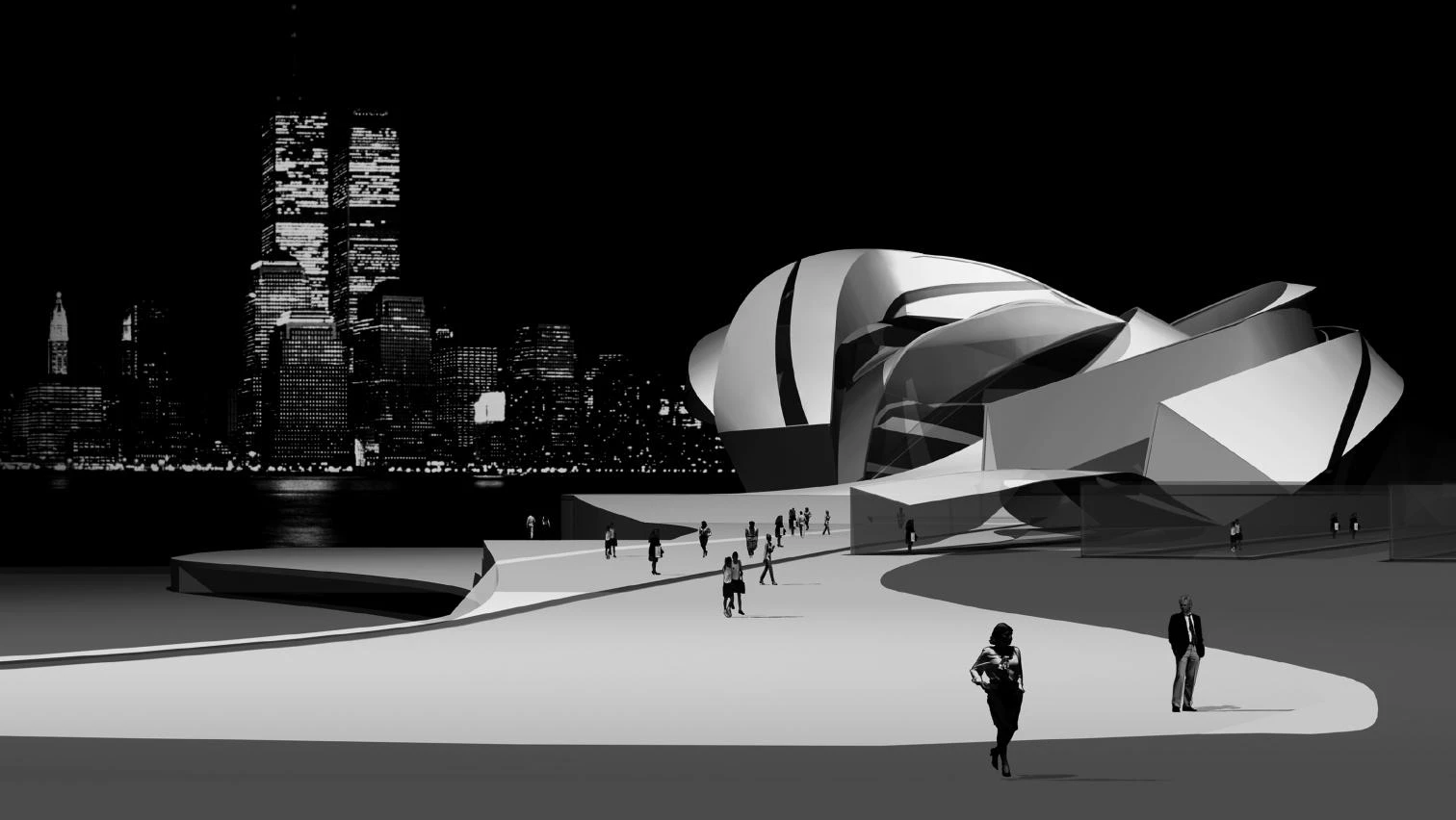

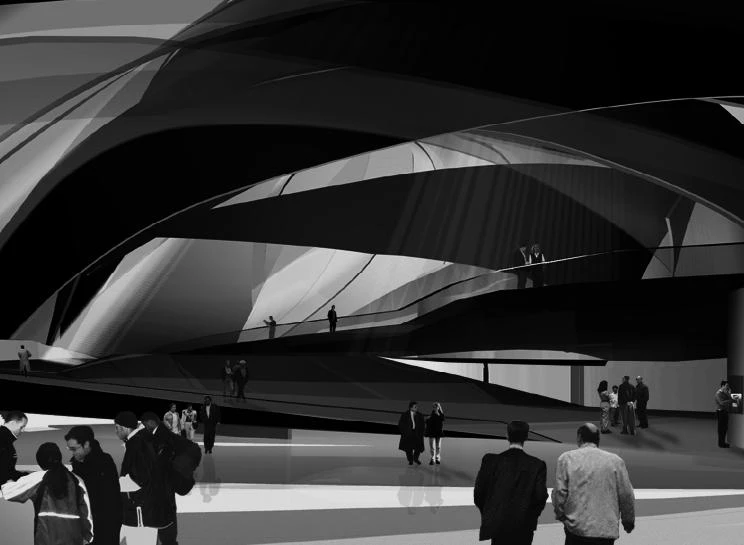

In New York, the dazzling glitter of the arts and science museum project by Peter Eisenman for the ferry terminal at Staten Island, and the subdued elegance of the Japanese Yoshio Taniguchi’s proposal for the extension to the emblematic Museum of Modern Art , also mark the two extremes of a cultural and architectural polemic between spectacle and memory.

The silence of Stockholm is not attributable to the architect, who knew how to raise his voice in the same Basque Country that is resounding with the media clamor of the Guggenheim. Neither is it a specifically Scandinavian thing. Moneo’s own master Jørn Utzon built the Australian continent’s most eloquent building, the Sydney opera house, and it was another Dane, Johan Otto von Spreckelsen, who gave Paris the great arch of La Défense. As for art museums, both the one that served Copenhagen during its own shot as culture capital in 1996 and the one that the American Steven Holl is finishing in Helsinki are closer to noise than they are to a hush. The placidness of the Stockholm museum comes, rather, from a syntony between Moneo’s capacity to interpret the requirements of place and the temperate symbolic demands of an egalitarian and satisfied society like Sweden’s, which has no need for too much architecture. Here, the serene skylights previously used at the Thyssen crown compact clusters of rectangular and square rooms strung together by a long luminous gallery, and the complex forms a peaceful and agreeable landscape against the neighboring church’s dome.

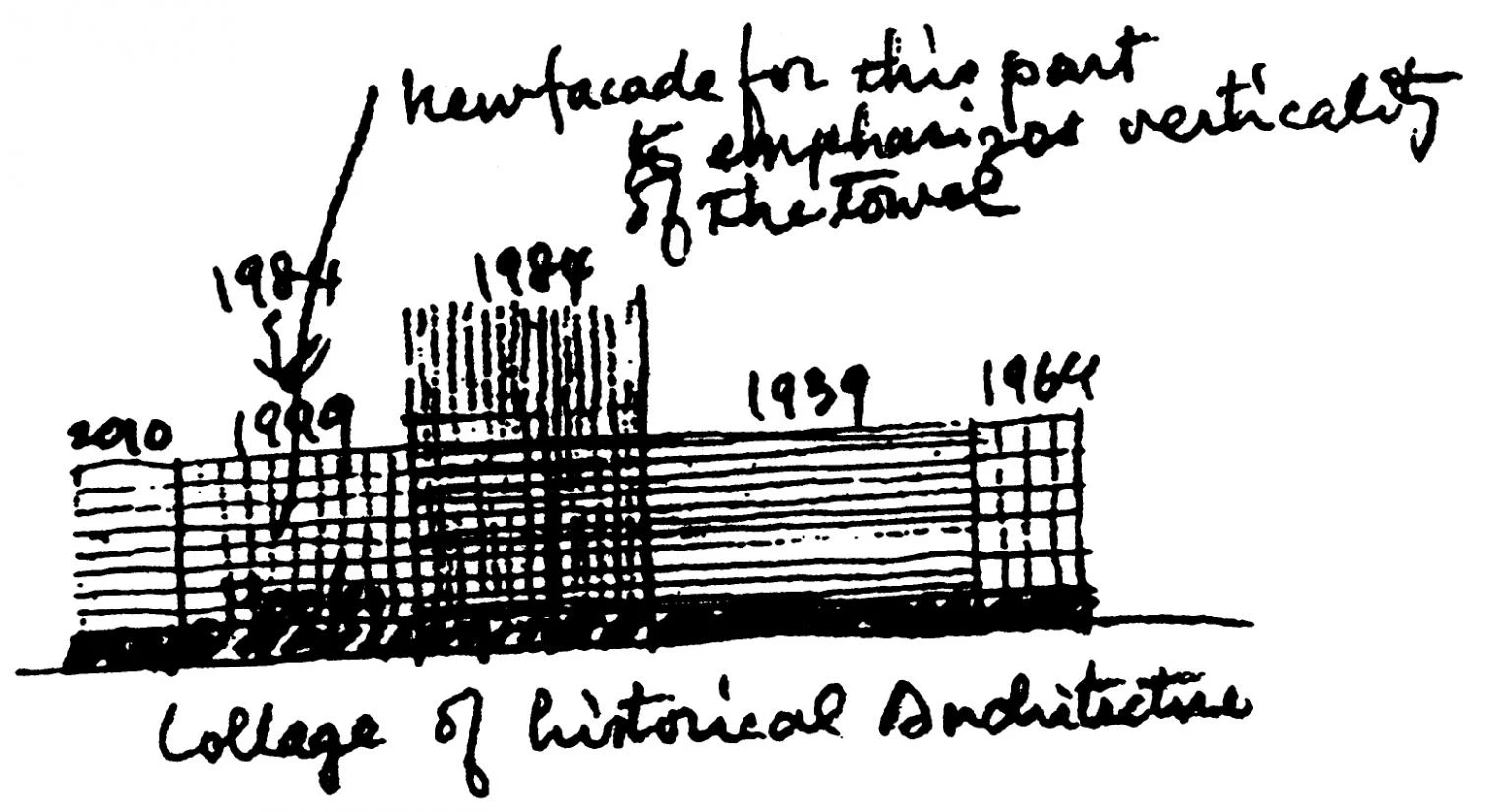

Bilbao and Stockholm illustrate perfectly the poles of the contemporary cultural debate, and significantly the two new grand projects of New York’s fermenting renaissance are situated in an identical rhetorical opposition. The ferry terminal on Staten Island, crowned by a museum of arts and sciences, will face Manhattan with a spectacular warped volume designed by the New Yorker Peter Eisenman; and the enlarged Museum of Modern Art will remodel this mythical institution with a series of austere glass and slate constructions by the Japanese Yoshio Taniguchi. Eisenman’s building, the architect’s first major commission in his city, connects the train, car and bus lines to the ferry docks, and extends the traffic flows to form the volumes of the museum, in a sweeping gesture of frozen movement. Its figurative ambition is comparable only with the TWA terminal built by Eero Saarinen almost four decades ago. As for Taniguchi’s project, it enlarges and reorganizes the MoMA with an extraordinary minimalist sensibility, articulating the different pieces of the museum and adding others with a degree of historical and urban precision that makes it both a tribute to the institution’s modern tradition and an exquisite, anonymous intervention in the dense fabric of midtown Manhattan.

Asian Courtesy

Taniguchi’s triumph in the competition for the extension of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the most coveted commission of recent times, is only the most visible expression of a tide of Asian fervor. The Tokyo Stock Market may suffer a crash in the coming year, but this will not affect the demand for Japanese architects. A 60-year-old Harvard alumnus who is as yet little known outside his country, Yoshio Taniguchi won over formidable adversaries like the Swiss Herzog & De Meuron, authors of the project for London’s new Tate Gallery, and Bernard Tschumi, dean of the architecture school of Columbia University. His proposal for the MoMA displays the detailed exactitude, conventional elegance and urban courtesy that have characterized the work of other transpacific Japanese, such as Arata Isozaki at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and Fumihiko Maki at the Center of Visual Arts in San Francisco, and was selected only months after his compatriot Tadao Ando capped first prize in the year’s other great American competition, for the Museum of Modern Art of Fort Worth in Texas, right next to Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Museum. If the Japanese Kazuyo Sejima managed to beat Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Helmut Jahn and Rem Koolhaas in the competition for Chicago’s IIT, a building in front of Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall which aspires to be an emblem of the city’s architectural rebirth, the Japanese would have accomplished a hat trick in three sacred places of modern American culture. Surely, if investors had as much confidence in Japan’s banks as American institutions have in its architects, the brokers at Tokyo would have nothing to worry about.

In New York, the dazzling glitter of Staten Island and the subdued elegance of MoMA mark the extremes of a polemic between spectacle and memory. Between the expressionist bonfires and crystallographic ice floes echo the screams and whispers of a year on the threshold of light and shade.