The third millenium began in Seattle on the 4th of December 1999. Many awaited it at Greenwich, under the huge tent that Richard Rogers built on the Meridian, in uneven competition with the Pacific atolls where the time zones situate the change of date, and in disdainful indifference to the computer chaos augured by the somber omens of the millennium bug. Nevertheless Y2K overtook the calendar, and first laid bare its political countenance and fractured social landscape in the incubator of the approaching future: the city that is home to Boeing, Microsoft and Amazon, where a coalition of poor countries, trade unionists and NGOs questioned before the world the inexorable trend toward globalization. In the cradle of grunge, Starbucks and Frazier, a popular revolt of a kind unheard of since the sixties brought on the failure of the World Trade Organization’s Millennium Round, cracking the armor plating of single market, single society and single thought. Convoked by the Internet and coordinated by mobile phones, Seattle demonstrators confronted Robocop policemen in an at once archaic and futuristic conflict that portends the coming century’s political debate between globalization and its discontents.

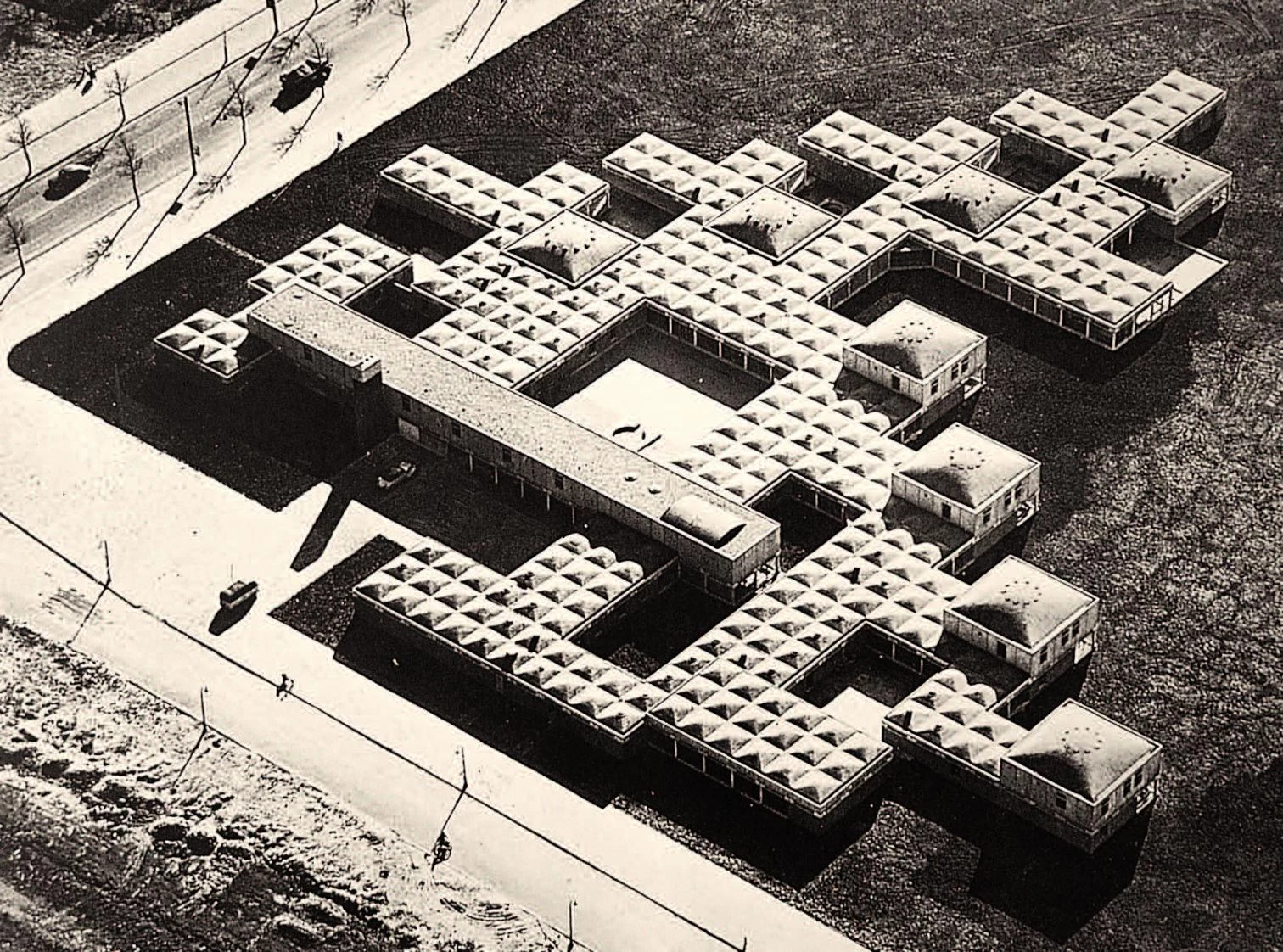

Winter brought the passing away of Aldo van Eyck, architect of the Amsterdam Orphanage (above), and instigator of the modification of the CIAM postulates, with concepts such as that of labyrinthine clarity.

While being honored with the Pritzker Prize, Norman Foster saw the inauguration of the Reichstag, the work that has shifted the center of gravity of a nation in search of visible symbols for its new geography.

Under the sign of globalization, 1999 saw the energetic boom of the American economy dampening the debut of Europe’s single currency, the timid recovery of Japan and the vigorous breakthrough of China, while the decomposition of Russia and the old socialist bloc was sprinkled with Balkan and Caucasian wars, Latin America swayed to the populist temptations of Chiapas or Chávez, and sub-Saharan Africa continued to fall in a black hole of misery and AIDS. And in this torn world (where, ten years after the disappearance of the Berlin wall, military, economic and cultural leadership is entirely in the hands of a single power, which even serves as a reticent venue for challenges to its hegemony such as that staged in Seattle), architecture still had its most stimulating experimental laboratory in Europe. Nourished by the polarization between Swiss and Dutch, European architecture wrote the year’s most brilliant chapters. American architects with a greater cultural and artistic vocation continued to come to the old continent for the receptive environment they do not always find in the United States, and the most relevant debates of American universities revolved around European episodes such as situationism or Team X: exercises on historical memory to which Weimar’s turn as culture capital contributed the inevitable revision of the legacy of the Bauhaus, that fountainhead of modernity we still feed on.

If we were to group the issues in seasons, winter would rightfully go to the Dutch, for whom Aldo van Eyck’s death in January was an incentive to look back on a career that had its heyday in the iconoclastic decade of the sixties, and whose rupture with the modern sclerosis of the CIAM inspired a hedonistic subversion that has stretched on to today’s epigones of Koolhaas, van Berkel or MVRDV, that form the pragmatic and surreal Rotterdam school, one of the poles of the European debate. The other pole is still in Basel, the city of Herzog & de Meuron, who wrapped up the year with an impressive handful of new buildings, and hometown of Peter Zumthor, who in March received the Mies van der Rohe Prize.

In August, Rafael Moneo inaugurated the Kursaal, two opalescent, glass dice stranded on the beach and rising from the mouth of the Urumea River, arriving in time for the forthcoming Film Festival of San Sebastián.

Spring would be Britain’s, with Norman Foster obtaining his long merited Pritzker, and perhaps also a bit Berlin’s, because the completion of the Reichstag and the German Parliament’s transfer to its new seat in April coincided with the announcement of the Pritzker winner, who would later receive the trophy in this same emblematic venue. May saw the Spaniard Santiago Calatrava, who had competed with Foster for the Reichstag project, obtaining the Prince of Asturias Prize. But the contest for honors would finally culminate during this season in favor of the Brit, who in June was bestowed the title of Lord by Queen Elizabeth II.

The star of the summer would be a masterwork of Rafael Moneo, San Sebastian’s Kursaal, which opened in time for municipal elections and was officially inaugurated in the hectic posh summer of the Guipúzcoan resort city, where its unstable volumes are a reminder of the still unresolved tribulations of the Basques. But in July alarms rang as well in Madrid, thanks to the demolition of Miguel Fisac’s Jorba laboratories, a concrete tower whose playful volumes had symbolized the optimistic spirit of the sixties, sparking a polemic about the preservation of the modern heritage - a particularly pressing issue in a city that neglects the conservation of the canopies of its horse racetrack, the best remaining work of the engineer Eduardo Torroja, a master of concrete whose centenary was celebrated in August.

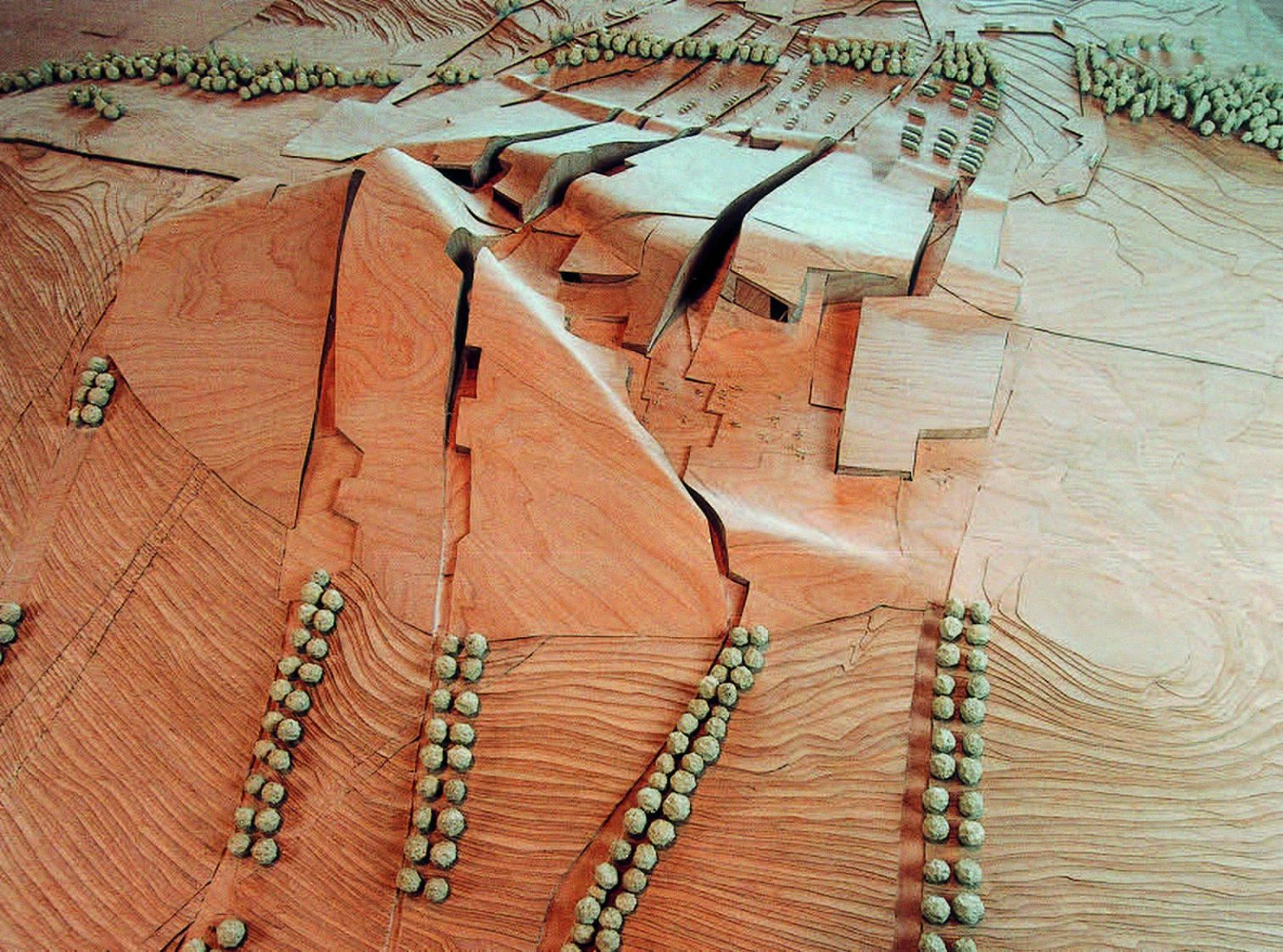

Another one of the summer’s cast of characters would be the New Yorker Peter Eisenman, who with a topographic proposal won the competition to build the Galician City of Culture in Santiago.

That same month announced the results of the competition for the Galician City of Culture in Santiago de Compostela. The New Yorker Peter Eisenman carried the day with an extraordinary topographic project that resounded through all of autumn, its impact totally drowning the three major Madrid contests of the season, won by Lamela (Telefónica), Cano (Royal Collections) and Nouvel (Reina Sofía Museum). Eisenman - whose master, the British Colin Rowe, passed away in November in Washington, D.C. - thus follows the European footsteps of his compatriot Gehry, who gave Bilbao his finest work and in 1999 finished a colossal office complex in the German city of Düsseldorf. And while the Galicians celebrated the Xacobeo with an avant-garde project, the Catalans held fiercely disputed regional elections in October, in time for which came a reconstructed Liceo, a new auditorium by Moneo, and a RIBA Gold Medal for Barcelona’s complacent torso.

But in Spain not all was good news, and December closed with the end of the ETA truce, after a fourteen-month impasse in terrorist actions, resituating the Basque Country in a convulsive landscape unworthy of the Guggenheim and the Kursaal. While the wounds of Ireland healed up, and the progress of peace-making in Palestine allowed Aznar to spend Christmas Eve with Arafat in Bethlehem, the sores of Kosovo and the splintered fracture of Chechnya remained open, undermining the perpetual peace of the global market with the demagogy of facts. A placid peace broken in Seattle by a Woodstock of solidarity determined to remind the world that the greater part of humanity is marginalized by the economic market, the political market and the symbolic market; marginalized by liberal capitalism, representative democracy and the media; and marginalized, too, by that phenomenon of culture and spectacle we are used to call architecture.