A glass pleat and an aluminum sphere have shaken off Manhattan’s lethargy. The faceted facade belongs to the new American headquarters of Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH), designed by the French Christian de Portzamparc, and the sphere enclosed in a glass cube is part of the Rose Center, the new planetarium of the Museum of Natural History, built by the New Yorker James Stewart Polshek. The former is a small, 23-floor skyscraper on 57th Street, with shops and offices for a firm that sells luxury and sophistication, and the latter an exhibition space fronting Central Park, for an institution that combines science, pedagogy and entertainment. Both are works of uncertain quality, linked by the exhibitionism that the spectacle of fashion and the spectacle of science demand. Yet New York critics have received them with an enthusiasm that has to be attributed to the architectural drought the city has been suffering for several decades now, and which has made the Big Apple an at once coveted and forbidden fruit.

The sphere enclosed in a cube by Polshek for the planetarium of the Museum of Natural History, and the faceted tower of Portzamparc for the French group LVMH are two of Manhattan’s architectural novelties.

Opened in December with the expected parade of stars, models and other famous – not to be missed of course by Hillary Clinton, First Lady and senate candidate for the state of New York – the LVMH building has been appraised by Herbert Muschamp in The New York Times, Ada Louise Huxtable in The Wall Street Journal and Paul Goldberger in The New Yorker with hyperbolic adjectives, and Architecture has put it on its cover, calling it “Manhattan’s best skyscraper in twenty years.” The fascination aroused by the building, which has cost $40 million, is of course not removed from its occupant, the world’s leading fashion emporium, owner of trademarks like Christian Dior, Givenchy, Christian Lacroix, Guerlain, Kenzo and Loewe. Surely it was natural to draw a parallelism between the haute couture of Bernard Arnault’s empire (which has rejuvenated old dames like Dior or Givenchy by putting such abrasive designers as John Galliano or Alexander McQueen on the front line) and the chic apparel with which Portzamparc has dressed the worn and vulgar body of a conventional skyscraper. In fact the leading American journals – the enthusiastic Architecture and the more skeptical Architectural Record (which prefers the Fox & Fowle tower on Times Square or SOM’s project for Pennsylvania Station) – both refer to the theses of Gottfried Semper (the 19th-century German architect and theorist who insisted on the importance of cladding) to give intellectual validity to a mask of folded glass that gives its inexpressive countenance the ambiguous seductiveness of the half-hidden.

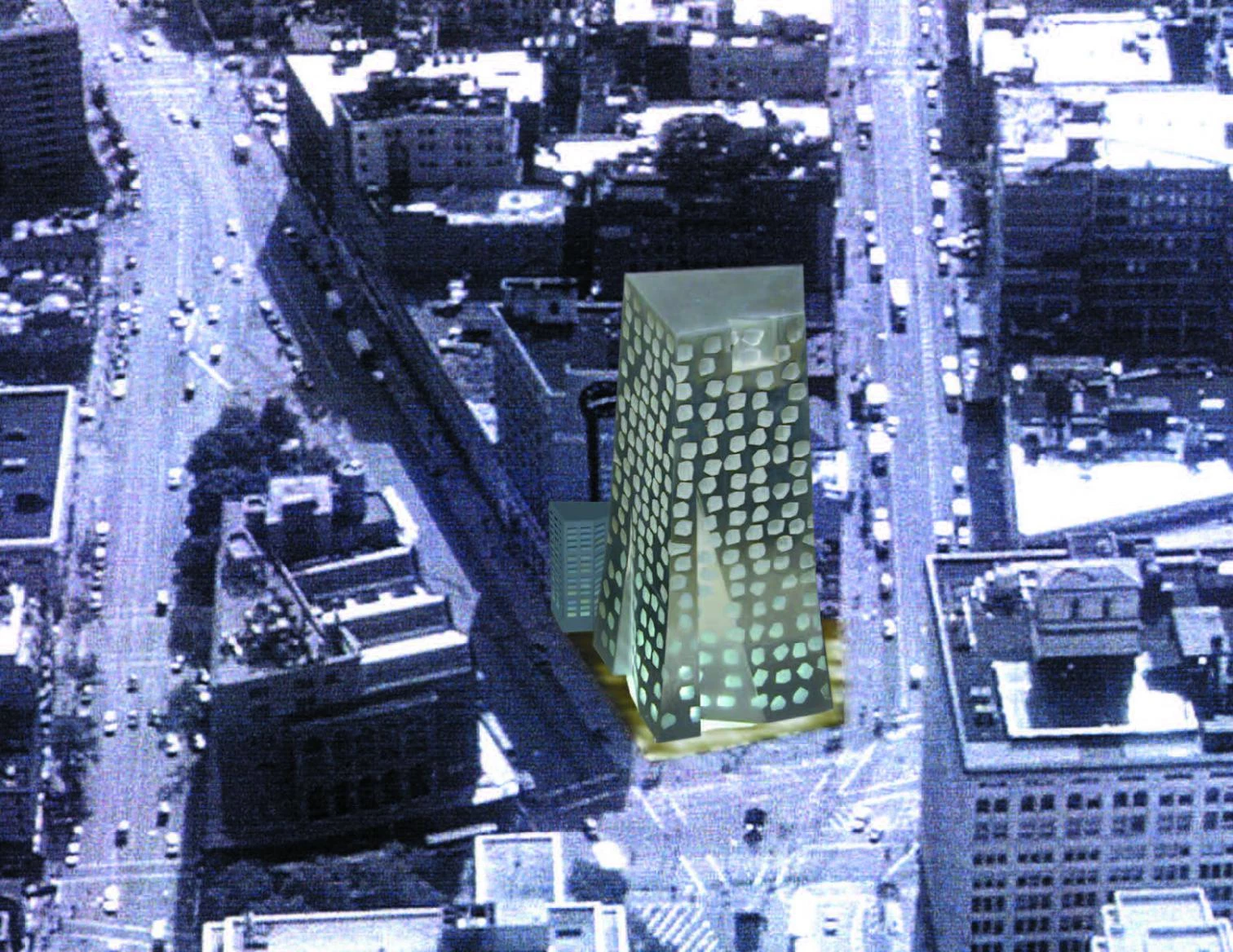

For the facade of this skyscraper boxed in be-tween party walls, Portzamparc, an amiable archi-tect of capricious forms – awarded with the Pritzker Prize in 1994, to general surprise – tried out different combinations of postmodern cylinders, pyramids and cubes before deciding on a glazed origami that intelligently capitalizes on the urban guidelines responsible for generating the staggered setbacks so characteristic of New York City, and whose folds of dyed and etched glass panels give the house of Dior a deconstructivist air, contrasting with the ironed severity of its granite neighbor, which Platt, Byard Dwell built in 1995 for Chanel. The trendy edges (which the building’s most vehement admirers interpret as the pleats of a skirt on a pair of crossed female legs) cover an otherwise trivial building, one where the only unique space is the Magic Room on top, a panoramic reception room which guests accede to from a mezzanine level, through a cinematographic curved staircase that reconciles the client’s scenographic needs with the architect’s figurative instincts.

Gehry has designed a larger-scale replica of his Guggenheim in Bilbao (above) for a new venue on the southern end of Manhattan; and Eisenman suggests remodeling its West Side with a wavy topography.

The planetarium of the Museum of Natural History was inaugurated in February, and also to generous critique, although only the architect has come to describe the colossal sphere as a “cosmic cathedral” whose platonic shape represents the universe, in the tradition of Boullée’s visionary 1784 project for Newton’s cenotaph or Wallace K. Harrison’s perisphere in New York’s 1939 World’s Fair. Built with a cost of $200 million, the 27 meter diamater sphere that has replaced the old planetarium is held in place by three pairs of tapering supports that make it seem weightless, and is inscribed in a formidable glass prism designed by the same specialists who worked with I.M. Pei at the Louvre pyramid a decade ago, charged with the same architectural mission: to give transparency to a venerated institution, pursue monumentality through elemental geometry, and hit upon the emblematic spectacularity without which contemporary museums look drowsy and insensitive to the demands of mass culture. Polshek, an architecture who specializes in cultural buildings and will be doing the Clinton presidential library in Arkansas, has decided to make the throngs of schoolchildren visiting this futuristic amusement park enter through an arch, and this postmodern gesture, more historicist than spatial, is perhaps the only element in the building he has been reproached for.

In any case, as a candidate for venue of the 2012 Olympics, NewYork City takes advantage of the current economic boom to gestate grand urban projects that will reinforce its financial and cultural lead in the world. The most important of these are situated on Manhattan’s West Side, a huge area of run-down docks, obsolete factories and railway tracks south of 42nd Street, for which the arts patron Phyllis Lambert organized, through the Canadian Centre for Architecture, a competition won by Peter Eisenman’s proposal of an undulating park and a stadium on the water’s edge. But the Olympic Committee, backed by Governor George Pataki and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, seems to have ideas of its own that will not necessarily tally with the New Yorker’s project.

Among the projects carried out by foreign firms in New York are the extension of the MoMA by Taniguchi (above), and the hotel for Ian Schrager in Astor Place by Herzog & de Meuron with Rem Koolhaas.

The other protagonists of this optimistic moment of New York architecture are its museums. The Museum of Modern Art will within months be initiating its extension works, following the project of the Japanese Yoshio Taniguchi, and the Guggenheim counterattacks with a big brother for Bilbao, designed by Frank Gehry for the southern tip of Manhattan, with a calculated cost of $750 million and the explicit purpose of competing with the MoMA in capturing corporate sponsors and private philanthropists. But the project that has aroused the most expectations is the hotel that – fronting the Cooper Union and for the owner of the Paramount and Royalton, Philippe Starck’s two New York hotels – will be jointly built by the Dutch Rem Koolhaas (recent Pritzker winner and designer of a Prada outlet in New York) and the Swiss Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (architects of London’s new Tate Gallery): two electrical poles promising current or sparks.

Meanwhile, both the LVMH tower and the Rose Center already reside in the mythic imagery of New York architects like set jewels: a cut diamond and an iridescent pearl at the service of glamour and leisure. In view of the fact that the city’s last icons – Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram, Wright’s Guggenheim or Saarinen’s TWA – were all built within the period between 1958 and 1962, one can understand the hungry impatience of critics to consecrate new idols and make the roads of architectural fashion traverse the Big Apple once again. The enlightened Ferdinando Galiani used to say that fashion is a dis-ease of the human soul; but between the Londoner Galliano of Dior and the Neapolitan Galiani of Diderot, all this Aragonese Galiano knows for sure is that, spectacle or disease, fashion and its geome-tries build today our landscapes and our visions.