Annus mirabilis, Annus horribilis

While the year of grand celebrations in Seville, Barcelona and Madrid began under the sign of spectacle, it ended in the shadow of economic crisis.

From euforia to despondency: rarely has the collective state of mind experienced such an extraordinary mutation in a single year. What began as an annus mirabilis for a nation that confidently readied itself for the fifth centenary of the discovery of America (or of the encounter or cultures, to use terms more in keeping with these times of political correctness) ended as an annus horribilis, and not only for England’s royal family, which put the term in circulation (after the fire of Windsor Castle and the separation of the Prince of Wales, who also then abandoned his classicist crusade), but for Europe as a whole, and certainly for our country.

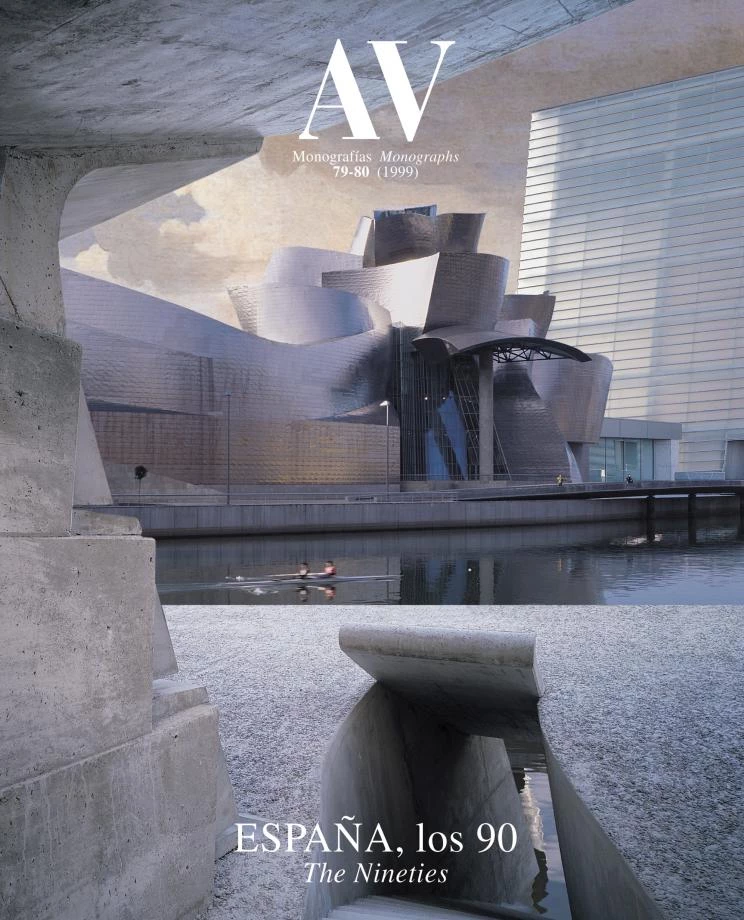

Surrounded on all sides by controversy, the pact signed by the Basque government to open a Bilbao branch of the Guggenheim Museum provides the opportunity to reuse abandoned industrial areas.

The year of Spain had arrived full of hope. During this period the Seville Expo and Barcelona Olympics would successfully take their course, and Spanish architecture was to relish a high moment of realizations and world projection, initiating a process of internationalization that would be reinforced by the large number of works being carried out here by foreign architects. But soon after the closing of the Games, Europe’s economic, political and military crisis combined with our own hardships to trace a landscape of discouragement, which was further aggravated by the serious ecological, demographic and sanitary menaces that are threatening our planet: a global village that technological advance has interconnected formidably, but where the resultant diffusion of knowledge has trivialized the media and commercialized culture.

Along with redefining the course of the River Guadalquivir and permanently transforming the relationship between the city and river, the Seville Expo drew in vital means for activating regional development.

Under the sign of spectacle, the year opened with a polemic agreement between the Guggenheim Foundation and the Basque Government for the construction in Bilbao of a franchise of the New York museum, following a project by the Californian Frank Gehry that gives sculptural expressivity to the geographic expansion of a foundation responsible for introducing the financial criteria of corporations to the world of art. Dazzling in its forms but deplorable in its aims, Bilbao’s Guggenheim promises to be the most brilliant end-of-century symbol of the Macdonaldization of culture, and this, paradoxically, in a Basque Country raided by a radical nationalism that waves the banner of differential identity.

In spring, and just a week apart, Paris and Seville inaugurated precincts subjected to the same logic of spectacle as the Bilbao museum: Eurodisney, the Mickey Mouse company’s first European theme park; and a Universal Exhibition that raised a hundred or so buildings on the isle of La Cartuja, linked to the city by a half-dozen new bridges over the river, the most visible one a gigantic harp designed by Santiago Calatrava. At once an organizational feat, a colossal fair and a formidable national propaganda campaign, the Seville Expo was also a costly regional development effort that renewed the communication and transport infrastructures of the depressed south.

Honoring the Badalona Sports Arena by Bonell and Rius (above), the Mies Prize paid homage to the quality of the new buildings of the Olympic Games, broadcast from the Collserola Tower by Norman Foster (below).

Summer was marked by the intensification of war in old Yugoslavia, to the horror of a continent that had not seen land battle in half a century and now helplessly contemplated the devastation of cities like Split, Dubrovnik or Sarajevo, with a systematic destruction of urban heritage that led to the coining of the term urbicide. Such degree of political and human catastrophe paled the good intentions of the world’s governments, gathered in Rio de Janeiro for the largest international meeting ever to be held, convoked for the sole purpose of protecting the planet from the ecological dangers that jeopardize its survival; or the pacifist Olympic spirit of athletes assembled in Barcelona to dispute a sport competition that failed to work out a ceasefire in the Balkans, but spelled resounding success for the host city and constituted the peak of collective euphoria and national self-esteem in the recent history of Spain, star of a show that was broadcast on TV, from the immaterial needle of Collserola Tower, to half of humanity.

Admiration for the urban transformation effected by Barcelona with the Games as pretext was materialized in numerous acts of recognition, the most significant of which was perhaps the awarding of the Mies van der Rohe Prize to a building that served as Olympic basketball court, from whence the United States ‘Dream Team’ amazed the world: the sport complex of Badalona, designed with contextual sensibility and geometric aplomb by Esteve Bonell and Francesc Rius. But the most prestigious tribute to an entire career, the Pritzker, also went Iberian this year, namely to Álvaro Siza, the master of Oporto whom Spaniards almost consider one of their own, to the point that he is the only foreigner ever to have won the gold medal of Spanish Architecture, a distinction which in 1992 fell upon the veterans José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún, while Japan’s Tadao Ando received the Carlsberg Prize and the Californian Frank Gehry added the Praemium Imperiale to his shelf of trophies. All this in the course of a year that saw the premature disappearance of a great master, the British James Stirling, shortly after completion in the German city of Melsungen of a building in which he returned to his origins, as a fake premonition of death; as well as the passing away of the Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi, the Canarian artist César Manrique, the Italian historian Giulio Carlo Argan and the British engineer Peter Rice, all of whom expressed the plural nature of architecture.

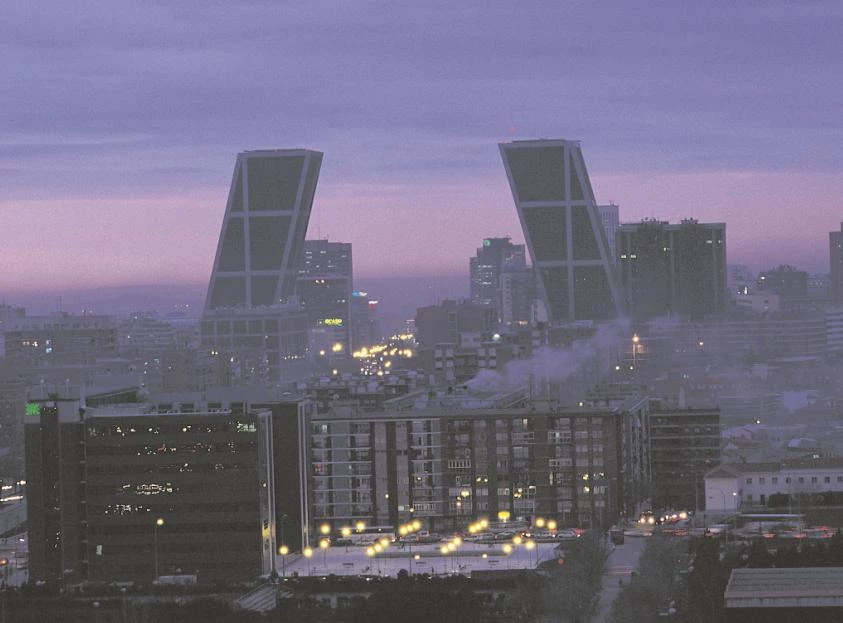

The crisis of the KIO group left unfinished the leaning towers with which Johnson and Burgee marked the end of the Castellana avenue, initiating an era of uncertainty after the excesses of the year.

With the Barcelona Olympics still fresh in the minds of all, autumn brought on an enormous hangover: Europe immersed in an identity crisis provoked by xenophobic reactions to economic decline, episodes of political corruption and the incapacity to stop war in Bosnia and Croatia; and the world shaken by the monetary turbulence produced by flows of frontierless capital, weighed down by the spread of the AIDS epidemic, and faced with planetary processes as potentially disastrous as the overheating of the earth or the uncontrollable increase of migratory currents. Such a climate dampened Madrid’s turn as European culture capital, which revolved around the October opening of the Thyssen Museum in Villahermosa Palace, intelligently remodeled by Rafael Moneo to house the world’s most important private art collection. The symbol of this low moment would end up being a pair of leaning towers built by the Americans Philip Johnson and John Burgee for the Kuwait Investment Office on Madrid’s Plaza de Castilla, which bankruptcy of the Arab group would leave unfinished. Their slant became an omen of Spanish instability, and a disturbing reminder of the fragility of the military, political and economic balances of power that sustain our convulsive world.