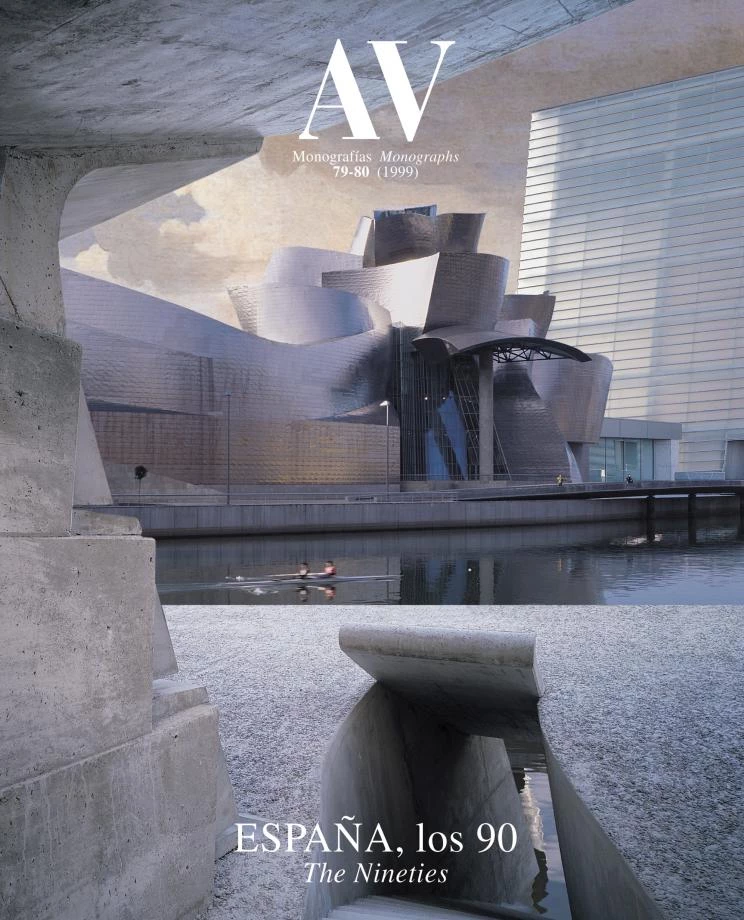

Europe, Year Zero

The convulsed forms of deconstructivism reflect changes in the map of world politics induced by the reunification of the two Germanies.

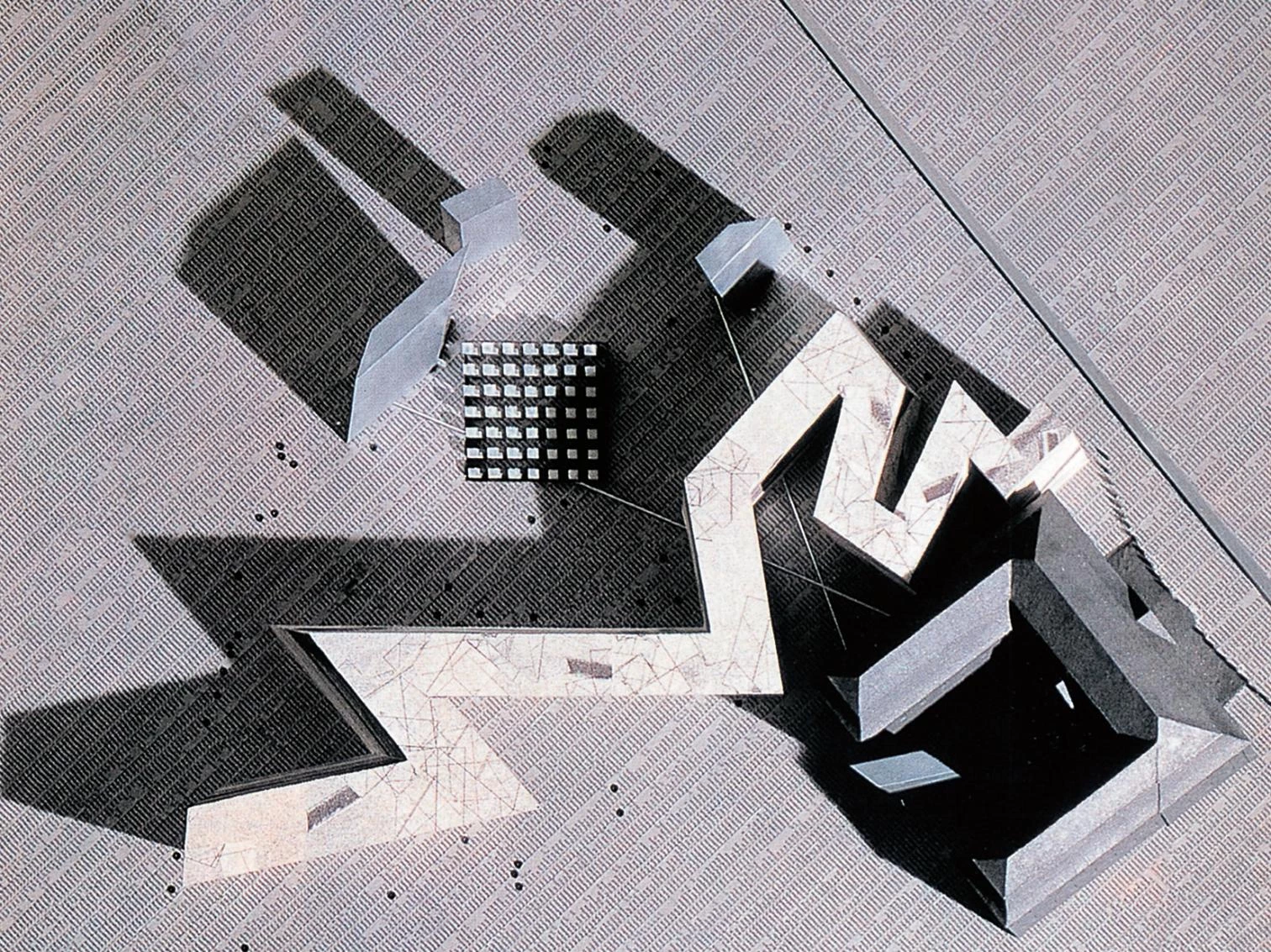

The century that began in Sarajevo ended in Berlin. In November 1989, the fall of the wall opened a new historical era of hopes and risks. If Roberto Rosellini’s film made war-torn Berlin the rubble-littered, famished scene of a year zero for a defeated Germany, the year zero of a Germany reunited in the wake of the collapse of Soviet power spoke of a Europe that welcomed the end of the Cold War, and Berlin was once again the crossroads linking history to the future. There, a Polish Jew with an American passport drew a museum in the shape of a bolt of lightning that zigzagged with luminous violence over the fabric of the city, one of the purest and most potent images of recent times. Conceived as an annex to the Museum of Berlin, to accommodate its Jewish section, Daniel Libeskind’s fortuitous scrawl symbolized the fractured and painful trajectory of Berlin Jews, but it also constituted the coming of age of deconstructivism.

The first winter of the decade brought about a consolidation of deconstructivism with a zigzagging Museum that Libeskind would build in Berlin, weaving the history of the city with that of the Jewish people.

In the summer of 1988, New York’s Museum of Modern Art had announced the rise of a new architectural language, inspired at once by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s ideas about deconstruction and by the unstable forms of the Soviet constructivist avant-gardes. Promoted at the same time that Gorbachov’s perestroika brought on a rapprochement between Russians and Americans, this fragmented language reflected the uncertainty of the contemporary world, while perhaps also auguring the end of the planet’s division into two politically and militarily opposed blocs. In 1990, the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Gorbachov and the MoMA’s exhibition on Russian constructivists coincided with the heyday of deconstructivism. Besides Libeskind with his brilliant Berlin project, spring 1990 saw two other Americans who had been featured in the 1988 exhibition completing important buildings. In Columbus, the New Yorker Peter Eisenman - who, incidentally, had built on Berlin’s mythical Checkpoint Charlie early in the eighties - finished the Wexner Center, his first really far-reaching work: and in the Vitra complex at Weil am Rhein, the Californian Frank Gehry built the chair museum, his first European building, a small but great expressionist and sculptural piece that opened new roads.

Commissioned by the Vitra chair factory, Frank Gehry erupts with his expressive forms onto the European scene, culminating a series of museums built by Meier, Stirling and Hollein in the Rhine River basin.

And while the future could be seen outlined in these turbulent forms, architecture’s institutions paid tribute to consummated careers: the Italian Aldo Rossi received the American Pritzker Prize, an honor long merited by his intellectual influence and by the poetic charge of his graphic work; the British James Stirling earned the Japanese Praemium Imperiale, yet another trophy for a master who was both modern and postmodern; the Dutch Aldo van Eyck was given the gold medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, a particularly late-coming acknowledgment of an oeuvre that had had its finest moment in the sixties; and the gold medal of Spain’s architectural institute also went to two veterans, Madrid’s Francisco Cabrero and Barcelona’s Oriol Bohigas. In May the International Union of Architects held its triennial congress in Montreal, and the event served as a context through which to present the Canadian Centre of Architecture (driven by Phyllis Lambert’s financial muscle and cultural ambition), while drawing attention to architecture in the Third World, with India’s Charles Correa winning the organism’s gold medal. All this in the course of a year that saw the death of Hassan Fathy, an apostle of self-build who had also once been a UIA medalist; of Gordon Bunshaft, who had won the Pritzker in his capacity as propagator, through SOM, of the Miesian credo; of Berthold Lubetkin, he who introduced modernity in Great Britain; of Alvin Boyarski, the pedagogue who through Frente al calor estival, Renzo Piano propuso una membrana de teflón tensada sobre los pétalos de hormigón del estadio de Bari, construido para el mundial de fútbol e inspirado en el perfil de las colinas de Puglia. To protect spectators from the summer heat, Renzo Piano proposed a Teflon membrane tightened over the concrete petals of Bari Stadium, built for the football World Cup and inspired by the profile of the hills in Puglia. the Architectural Association renewed the entire London scene; of the New Yorker Lewis Mumford, the great historian and critic of culture; and the Spaniards Luis Moya, a geometric builder of archaic architectures, and José María García de Paredes, a modern master of musical sensibility.

To protect spectators from the summer heat, Renzo Piano proposed a Teflon membrane tightened over the concrete petals of Bari Stadium, built for the football World Cup and inspired by the profile of the hills in Puglia.

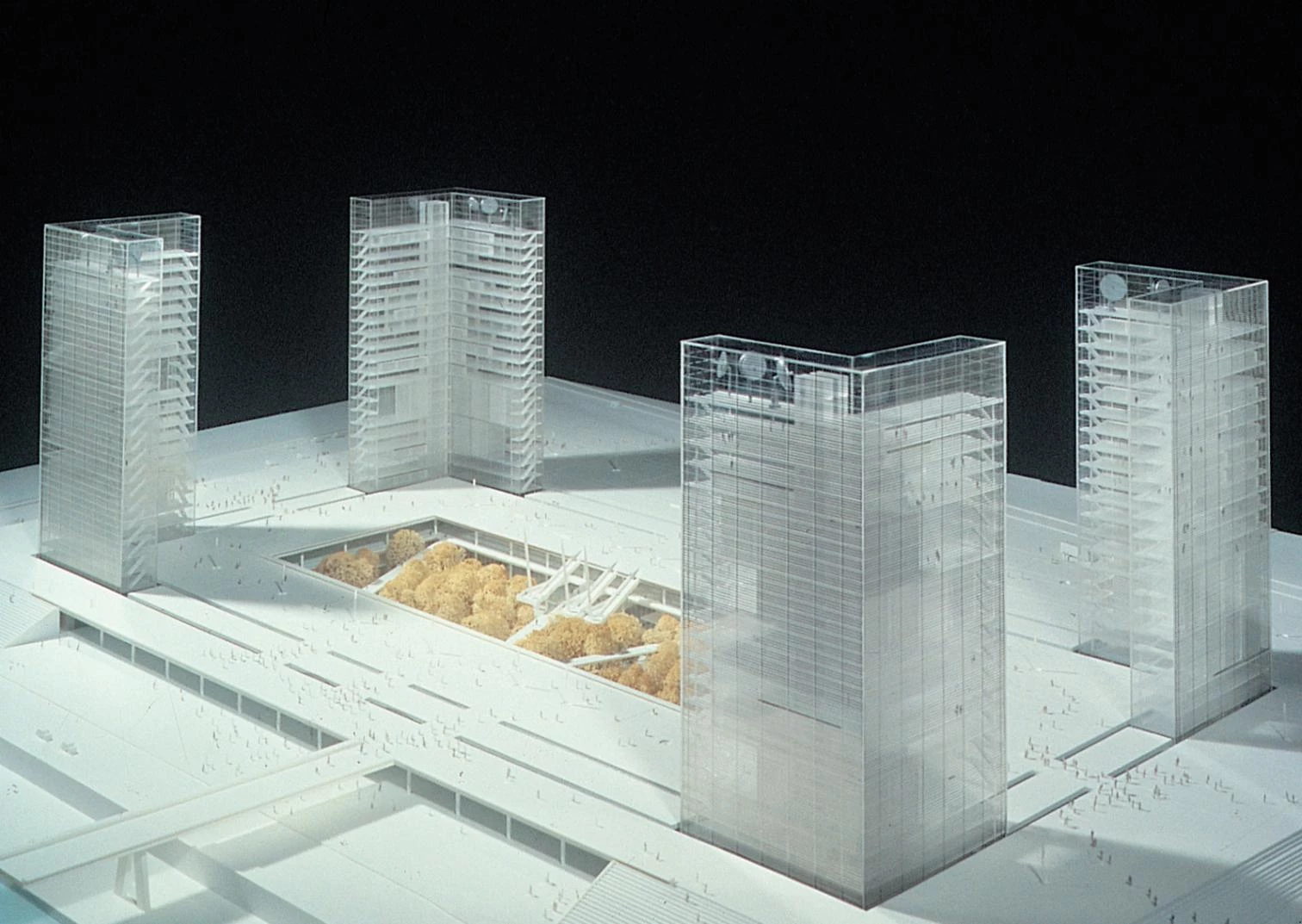

In summer the focus shifted to Italy, where football’s World Cup was disputed in renovated stadiums that offered more architectural than athletic satisfaction. Germany turned out the champion, as befitting the year of its reunification, but the true star was the new stadium of Bari, built by Renzo Piano as a lightweight flower of concrete petals. It was a great season for the Genoese architect, who in the bay of Osaka initiated the construction of Kansai Airport, an enormous terminal of tense geometries on a man-made island. Another colossal building, the Très Grande Bibliothèque in Paris - the last of François Mitterrand’s presidential projects - also began to go up, as designed by young Dominique Perrault, who had won the competition with four huge towers resembling open books delimiting a monumental urban esplanade. But football and titanic works aside, the hot news of the summer would come in August with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, a traumatic convulsion in the world’s oil hub that definitively put to the test whatever new order had emerged from the ruins of the Berlin wall.

Cuatro torres transparentes, abiertas como libros, delimitan el patio ajardinado al que abren las salas de lectura de la Gran Biblioteca de París, diseñada por Dominique Perrault como un icono junto al Sena.

In Spain, meanwhile, assessments of the socialist decade left a bittersweet aftertaste, with formidable political and economic achievements interspersed with not a few cultural deceptions and some incidents of corruption. The completed Senate extension and ongoing Congress enlargement reflected a general indifference to the architectural symbols of democracy, with the country mustering energy and concentrating attention on preparations for the two events of the Columbian centenary, the Expo of Seville and the Olympic Games of Barcelona, each of which was generating a cumulus of projects of variable quality. Perhaps nothing represented this prosperous and narcissistic moment of Spain as well as two interior spaces remodeled for entertainment and leisure: the Ávila towers in Barcelona, by Alfredo Arribas, and the Teatriz restaurant in Madrid, by Philippe Starck, perfectly expressed the demands of a smug and hedonist society. The return to the country of its best architect, after five years as chairman of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, promised a rise in the temperature of the debate. The renovation of Villahermosa Palace to house the Thyssen Collection was Rafael Moneo’s very cautious first intervention after the homecoming, but the leaning glass prisms that won him the competition for San Sebastian’s Kursaal augured more lively controversies: those fractured cubes bespoke the risks and uncertainties of Europe on its year zero.