In Berlin, Zumthor is building a box of concrete bars which will house a center of documentation on Nazi crimes; and Eisenman has designed a forest of concrete prisms in memory of the murdered Jews of Europe.

Germany subjects memory to a plebiscite. The general elections are setting Helmut Kohl against Gerhard Schröder, but will also be a tug of war between two different ways of remembering the nation’s past. The Christian Democrat chancellor defends the construction in Berlin of a huge monument to keep alive the memory of the Holocaust, the extermination of six million Jews that is the greatest dishonor of German history; his Social Democrat rival, in whose cabinet Michael Naumann would be in charge of culture, has declared himself opposed to the memorial, insisting instead on the urgency of rebuilding Berlin’s Stadtschloss, the old Baroque palace of Prussian kaisers. In the difficult transition from ‘republic of Bonn’ to ‘republic of Berlin’, the memorial and the palace have triggered a formidable political and popular debate on history and its built images, a cultural and architectural controversy that is a sequel to the polemic sparked four years ago on the question of the reconstruction of the Reichstag.

The open wounds of an ominous past have made Berlin’s skin a symbolic seismograph. Long before the fall of the wall, the city held a competition for a monument in memory of the victims of national socialism, to be erected over the site of Prince Albert’s old palace, general headquarters of the SS during the Hitler regime. The monument was never carried out, but the vehement response to one of the contestants, Rafael Moneo, says much about the temperature of opinion at the time. With sober sensibility, the Spaniard proposed an imposing and hermetic cylindrical enclosure formed by concentric circumferences of brick, a forceful and archaic volume that resembled a Roman mausoleum and rounded off the perspective of one of the bordering streets. It was a solemn and elegiac proposal, but many Berliners saw it as a provocation because of its classical elements that could evoke the Nazi architecture of Albert Speer. Symmetry, urban axes and opacity were then considered ‘politically incorrect’ in Germany. (Rising on the site today is a large box of concrete bars designed by the Swiss Peter Zumthor to house a center for the documentation of Nazi crimes.)

At the two extremes of Unter den Linden, the Reichstag and the Stadtschloss constitute two symbols of power of extraordinary force. The restoration of the former and the replacement of its dome, according to the project of the British Norman Foster, as much as the still undecided reconstruction of the latter, have both been the object of wide political and popular debate about history and its built images.

Years later, with the wall gone under and Berlin decidedly the capital of a unified Germany, the matter of reconstructing the old parliament – burned down in 1933 and devastated by artillery fire in 1945 – once again began to awaken old demons. The Reichstag symbolized the empire, and one inevitably relates it to the Germanic expansionism that triggered two European wars: the photo of the Soviet soldier waving the flag of the hammer and sickle over its smoky ruins is the canonical representation of the fall of Berlin, a mythical image of Germany’s defeat and the end of World War II in Europe. When the architect Santiago Calatrava, in the design competition that was organized, proposed to reconstruct the building with a glass dome resembling the original, the censure was of the same tone as that previously expressed regarding his compatriot Moneo: the dome is more associated with absolute power than with democratic consensus, and the mere act of crowning the Reichstag connotes a historical and symbolical continuity of a politically undesirable nature.

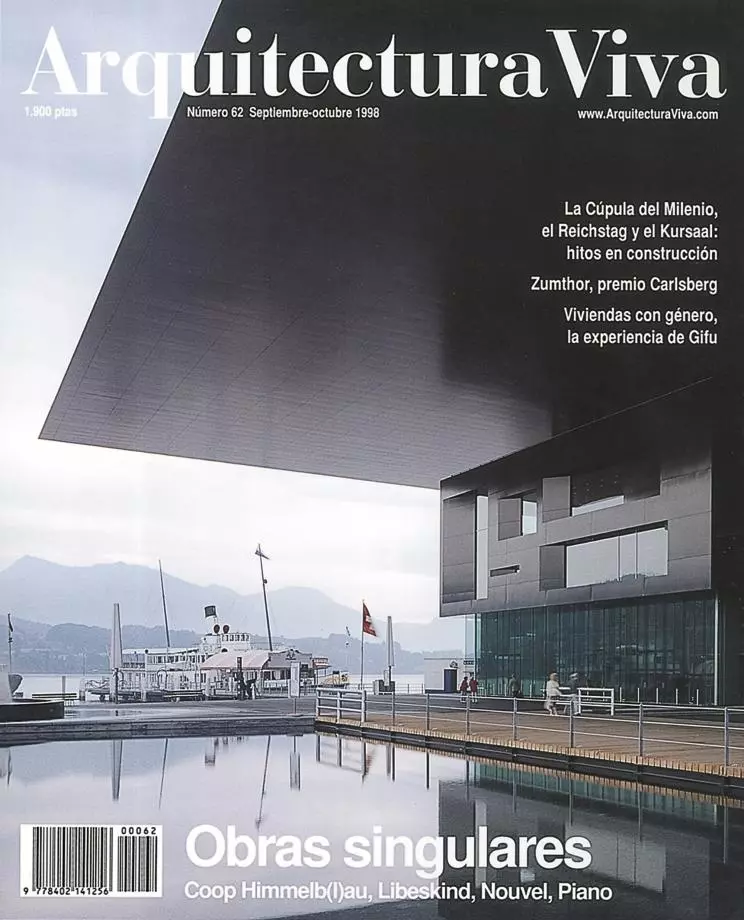

But architectures tend to be obstinate, and although the commission finally fell upon Norman Foster, who conceived a monumental futuristic canopy over the building, he had to rework his proposal in the long run, abandoning his baldachin for the same glass dome which Paul Wallot had crowned the Reichstag with a century before. The dome is currently at a very advanced stage, and though its external shape invokes ominous echoes, both its civic function and its technological statement work to distance it from the old Reichstag. On one hand, the dome is a public lookout over the city and into the parliamentary session hall, in the latter case symbolically placing the electorate above the elected; on the other hand, it incorporates an environmental control system that uses natural energy, stressing parliament’s dutiful leadership and ex-emplariness in the use of resources.

Many of these political and symbolical concerns have returned to the limelight of Berlin polemics with another memorial – to the victims of the Holocaust – and another reconstruction – of the Stadtschloss. In the case of the two reconstructions, there is an essential difference: whereas a substantial part of the Reichstag’s original masonry had been conserved, there was absolutely nothing left of the huge 17th-century imperial palace. Seriously damaged during the war, this was torn down altogether in the early fifties by the communist leaders of the Democratic Republic of Germany, who then used part of the site to erect a deplorable ‘Palace of the Republic’, but as asbestos was used for its construction, it cannot be easily recycled. Although some old Germans of the East are fond of their deteriorated socialist palace – one of their last lingering sings of identity – the real obstacle to building a replica of the Prussian palace on the site is the huge cost it would incur.

Situated at the two ends of Unter den Linden, the Reichstadt and the Stadtschloss are two symbols of an extraordinarily vigorous and menacingly efficient power which they seem to want to exorcise and invoke at the same time. Shortly before Christo wrapped the Reichstadt in canvas, making it disappear so that it could regenerate into something more benign, the people of Berlin spread painted canvases on scaffoldings to simulate the volume and facades of the old Stadtschloss on its original site, invoking its memory with deceivingly ephemeral architectures. Perhaps because such images stir up so much historical slime, or because such blanketed ghosts call up so many spirits long believed to have vanished, the inevitably compensatory memorial to the victims of the Holocaust takes on a necessary and urgent character.

Proposed a decade ago by the television commentator Lea Rosh, the monument in memory of Europe’s murdered Jews immediately received the support of the intelligentsia, and with a huge piece of land near the Brandenburg Gate obtained in 1993, a competition held in 1995 was won by the painter Christine Jackob-Marks, who conceived a sloping flagstone as vast as two football fields on which the names of the 4.2 million exterminated Jews who it has been possible to identify would be inscribed. The popular and political rejection of the project’s funerary character made it necessary to organize a second competition two years later, and four finalists were selected: Jochen Gerz, a Paris-based artist who proposed to erect 39 luminous masts with the question ‘why?’ asked in different languages; Gesine Weinmiller, who made a series of diagonal walls merge visually to form a star of David; Daniel Libeskind, author of Berlin’s Jewish Museum, who conceived large screens riddled with arbitrary voids; and finally Peter Eisenman in conjuntion with Richard Serra, whose idea of a neat labyrinthian grid is the project most likely to be carried out.

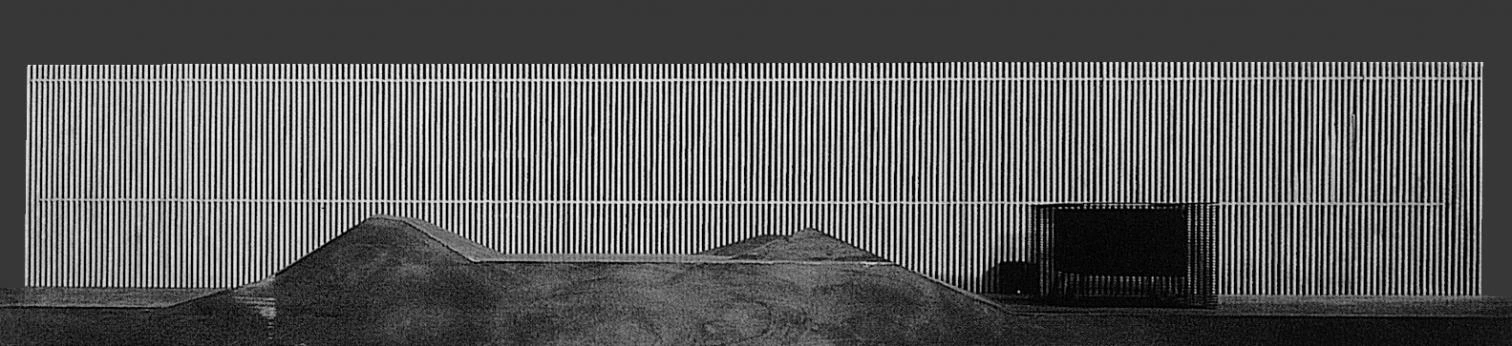

The proposal of the New York architect (the sculptor Serra decided to withdraw from the project) creates an at once geometric and random landscape with 2,700 concrete prisms of different heights, arranging these in a regular grid with gaps of less than a meter along which visitors can circulate. Both the ground of these corridors and the tops of the blocks form warped surfaces, and the entire thing waves as if blown by a soft breeze, evoking a wheat field, or an infinite and peaceful cemetery where gravestones stretch on in the horizon the way the repeated crosses of a World War I necropolis disappear into the gentle slopes of northern France. This placidly melancholic character of the monument’s full view contrasts with the predictable experience of one finding his way between the concrete prisms, subjected as he will be to the undefinable claustrophobic anguish of regular and narrow passageways: a Cartesian maze that disorients with its extreme order, and that laconically but eloquently exposes how reason breaks down when method takes priority over purpose, when the grid governs one’s route and destiny.

Günter Grass, who was among the first promoters of the memorial, recently called for the abandonment of the project. The writer believes that the horror of the Holocaust cannot be expressed by an abstract monument of oppressive dimensions. Some argue that perhaps the best memorial is continued discussion about it, since in this way the issue stays alive, without any ‘final solution’ out there serving to seal the past. Others, with a lucidness not lacking irony, have suggested that the true memorial to the victims of the Holocaust is the city of Bonn, and that moving the capital back to Berlin can only be interpreted as a collective amnesia. Perhaps for this very reason, and also because Eisenman’s project is so charged with emotion and poetry, Germany should not transfer its institutions to Berlin without marking the now bustling face of the old Prussian and Nazi capital with the ash of repentance. If Günter Grass had consulted the leading characters of his long story, I am convinced that, “without consideration for the dead or for the gravestones,” Theo Wuttke and Ludwig Hoftaller would have agreed.