The Four Seasons of the Year After

After the passions of 1992,1993 was a year of hangovers, low profiles and everyday dramas. The emblematic year of the 5th Centenary could have been summed up by four forceful silhouettes in four big Spanish cities: the steel octopus designed by Frank Gehryfor the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao; the giant harp of the bridge by Santiago Calatrava in Seville; the tense and elegant needle of the telecommunications tower by Norman Foster in Barcelona; and the leaning KIO towers, an illstarred work by Philip Johnson and John Burgee in Madrid. A project, two realizations and an unfinished work which shared a desire to inscribe themselves in Spain’s most representative urban profiles.

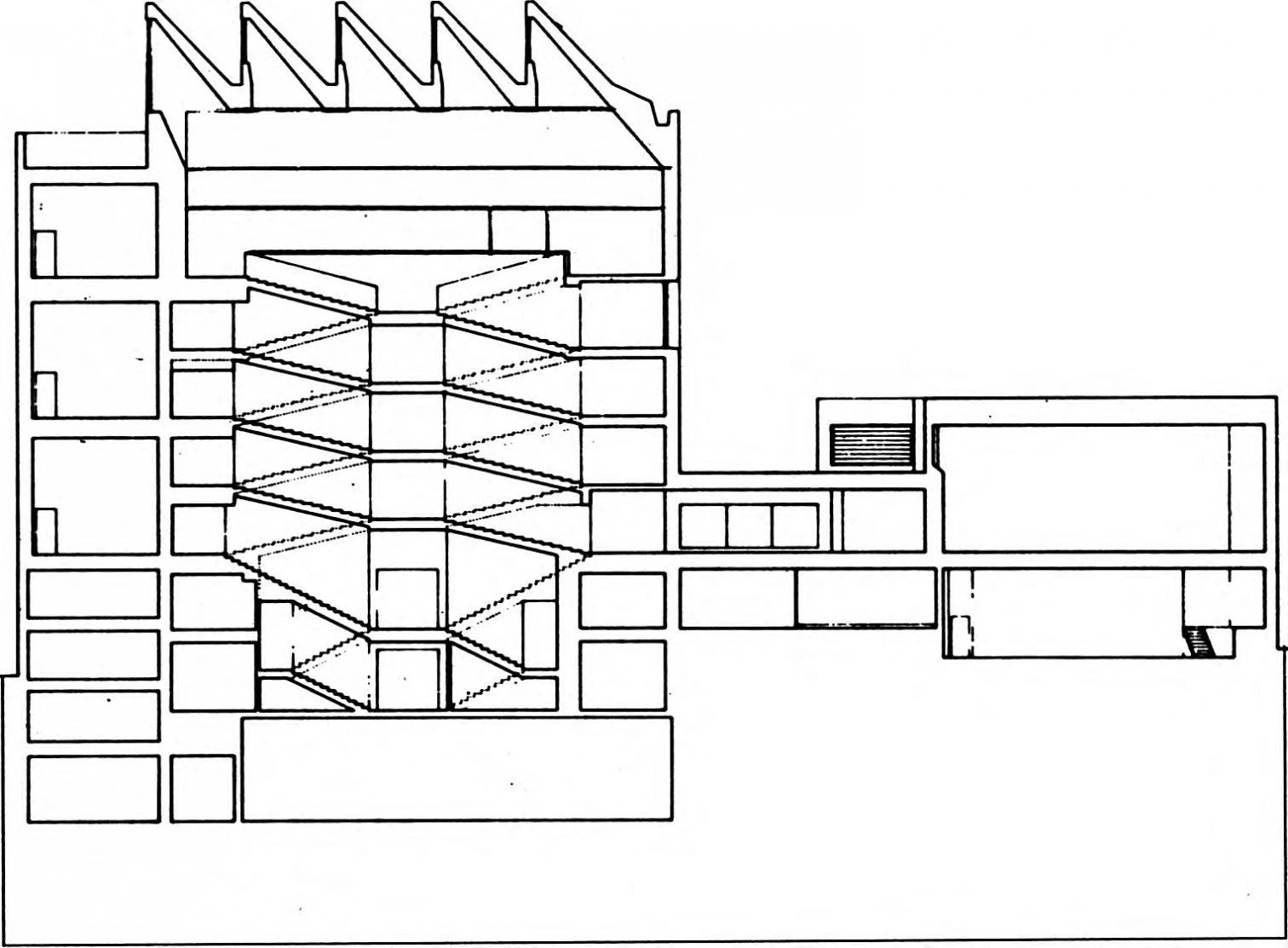

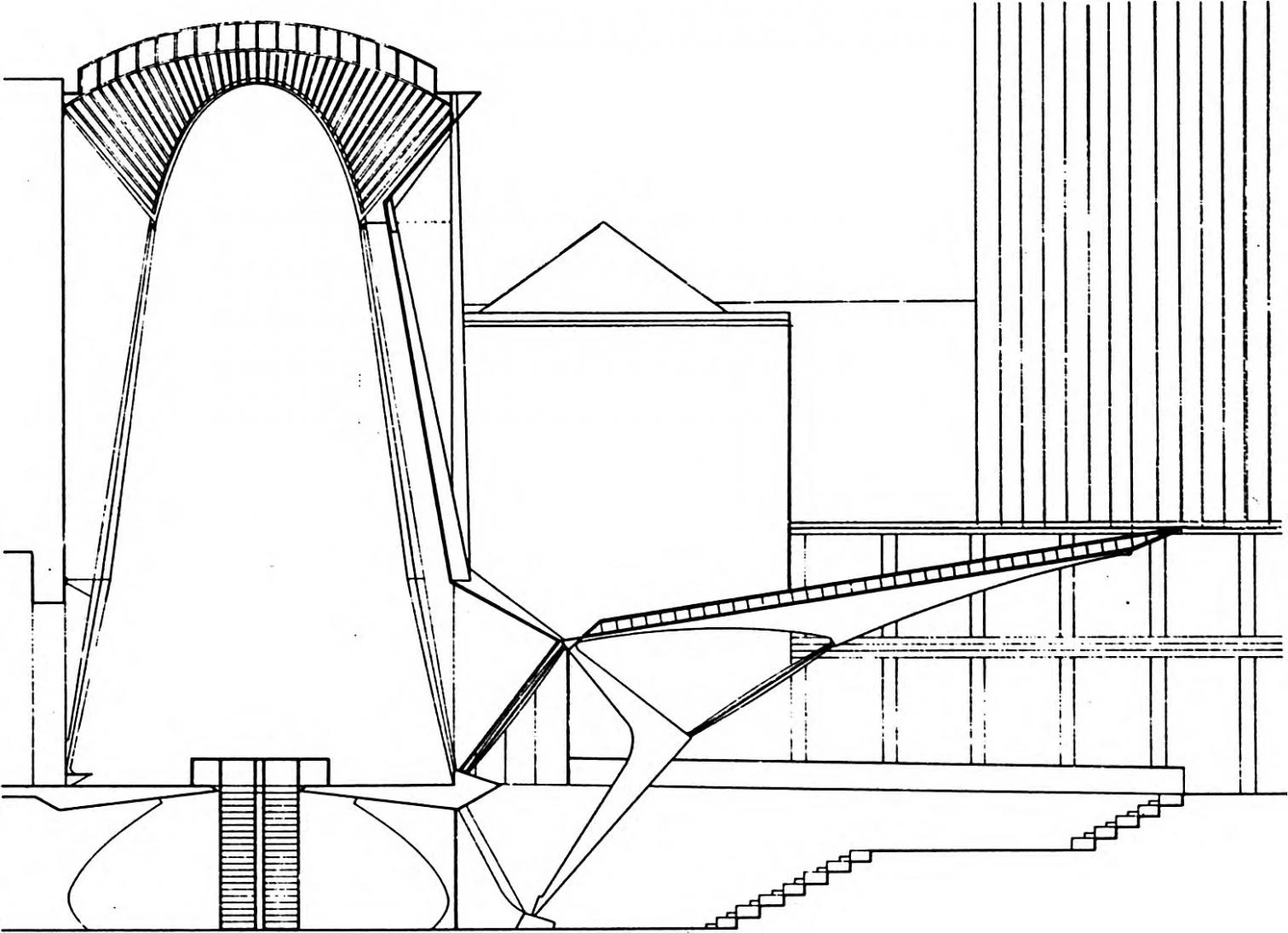

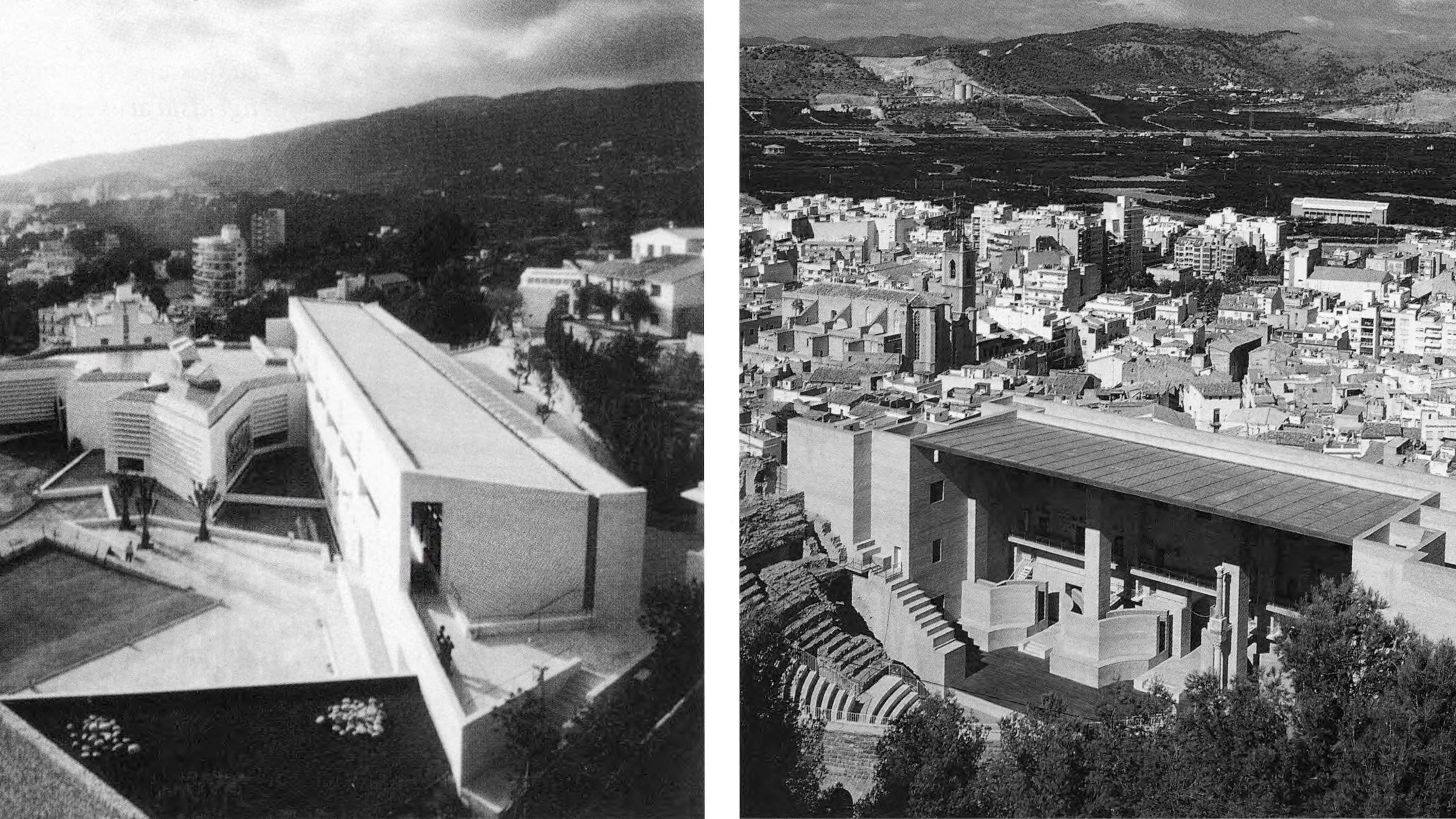

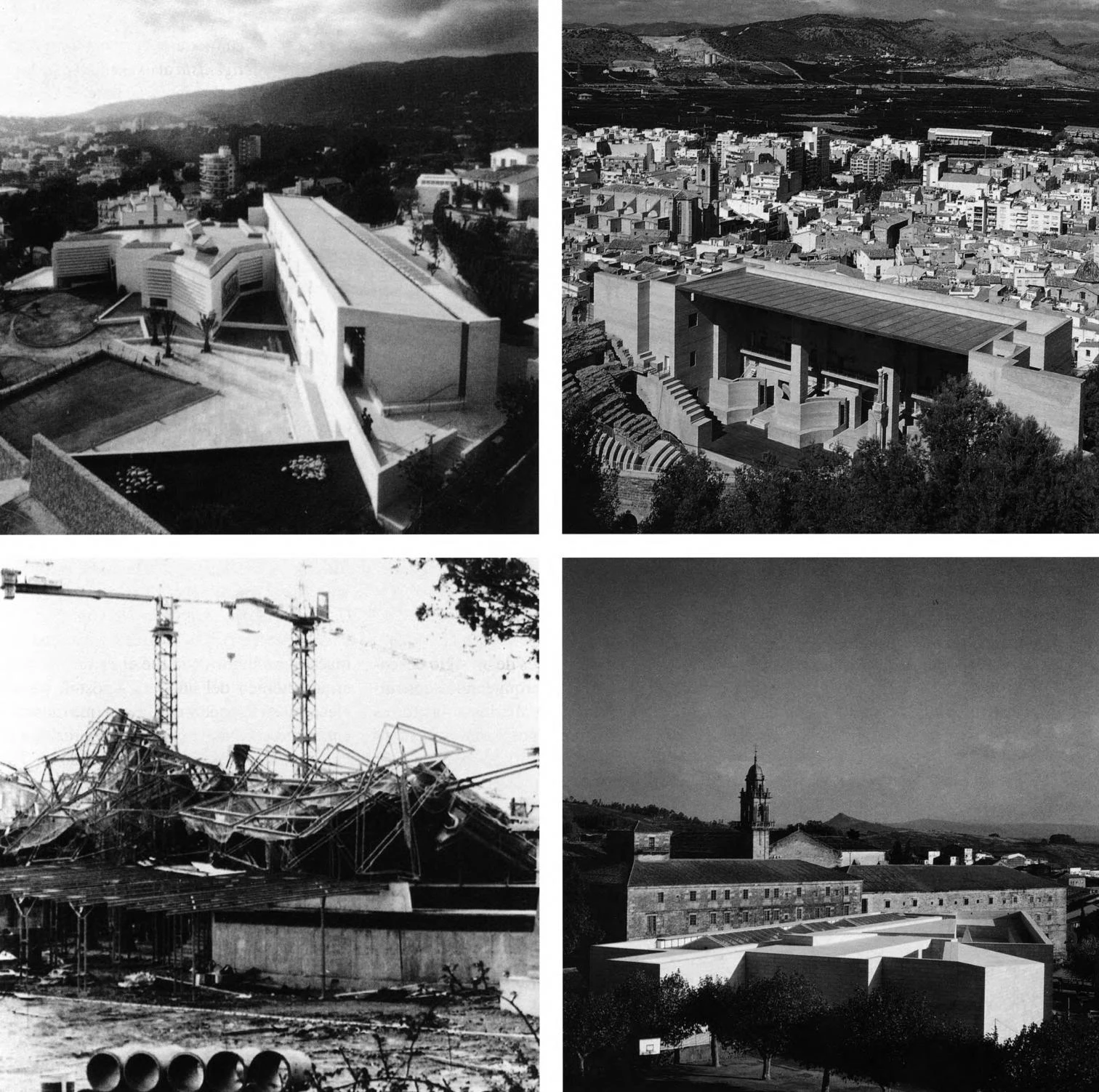

By way of contrast, the past year might be summarized through four sharp vignettes in four small cities: the Pilar & Joan Miró Foundation built by Rafael Moneo in Palma de Mallorca; the Multi-Sport Center by Enríe Mir alies in Huesca; the restored Roman Theater by Grassi and Portaceli in Sagunto, Valencia; and the new Galician Center for Contemporary Art designed by the Portuguese Alvaro Siza in Santiago de Compostela. Two museums, an accident and a controversy marked the four professional and aesthetic seasons of a year that shifted protagonism toward the brinks, splashing in a diffused malaise and disoriented uncertainty.

Moneo, Winter in Mallorca

Winter began on a lukewarm and literary island where Rafael Moneo finished a starshaped museum to house the work of Joan Miró, whose centenary was to be celebrated in the course of the year through successive exhibitions in Madrid, Barcelona and New York. For the architect it was to be an especially auspicious year, with the completion of his own house in Mallorca, the inauguration of his first American work, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, and the happy news of the definitive sale to Spain of the Thyssen Collection, whose 800 canvasses will stay for good in the peaceful peach atmosphere of the Villahermosa Palace, so beautifully renovated by Moneo in 1992.

Aside from Miró, the Museum of Modem Art in New York exhibited Santiago Calatrava, whose sculptoric engineering was thus consecrated internationally, making this native of Valencia with offices in Paris and Zurich, together with his victory in some competitions, the architect of the year.

The Dark Spring of Miralles

April was cruel to the most admired artistic talent of young Spanish architecture, who saw his more important commission collapse in the early hours o f a cold springtime morning. The anti-gravitational expressionism of the Huesca Sports Center pulled down with it the experimental innocence of a significant part of Spain’s recent architecture, which during the prosperous eighties received a wealth of confidence and freedom made patent by such daring and difficult buildings as the Center for Eurhythmies Sports in Alicante, completed in 1993 by Miralles himself.

The fall of Huesca was the Challenger of deconstruction, and an ironic metaphor o f a world fractured by something more important than merely stylistic earthquakes. The economic, political and military catastrophes of our torn century brought so much demolished architecture to the front pages of newspapers - New York's twin towers bombed by Islamic fundamentalists, London's City devastated by the IRA's violent nationalists, or the monuments of Florence and Rome damaged by the same disintegration forces that are ripping Italy and Europe apart-that the shaky provocations of deconstructed architecture seem like trifles when compared to this lunatic destructive violence which in the city of Sarajevo has attained the category of an ominous symbol.

The architectural year of 1993 might be summarized by means of two art museums, a debate and an accident: the Pilar & Joan Miró Foundation in Palma de Mallorca by Rafael Moneo; the controversial Roman Theater in Sagunto by Grassi and Portaceli; the hapless Multi-Sport Center in Huesca by Enric Miralles; and the Galician Center for Contemporary Art in Santiago by Alvaro Siza.

A Roman Summer for Grassi

The Milanese architect spent a hot summer in Sagunto amid court hearings and controversies. His audacious reconstruction of the Levantine town's Roman theater stirred endless debates, long-winded judicial claims, and a dramatic break between popular appreciation for the monumental ruin and the intelligentsia's unconditional support of Grassi's pedagogical extremism. The uncertain ownership of collective memory and the sentimental character of our built heritage were made evident in this emblematic conflict between invention and memory.

The social and political seizures of the socalled *new world disorder' have forced us to look back to old realities of an ethnic or spiritual nature. The symbolic and sacred dimension of architecture came to the fore during the year in the form of new religious buildings, from King Has san II's enormous mosque in Casablanca to the new cathedral of Managua, designed by the Mexican Ricardo Legorreta, not to mention the consecration of Madrid's finally finished cathedral by Pope John Paul II.

Siza and the Autumn of the Patriarch

Like a late and luminous fruit, the autumn of St. James brought with it the opening in Santiago de Compostela of the Galician Center of Contemporary Art, a fractured white building by the Portuguese master which was the finest architectural result of the Apostle's Holy Year, an electoral year in Spain and Galicia that sealed the continuity of two unbeatable patriarchal politicians, Felipe González and Manuel Fraga, hardened survivors of the loss of prestige of the public sphere, and of the corrosion of democratic conventions.

The year ended with the fast shapes of Zaha Hadid's first materialized building, the Vitra fire station at Weil-am-Rhein, or Jean Nouvel's latest, the Convention Center of Tours: swift and polished images of concrete or steel which transmit a meshed, rapid and crepuscular message, built figurations o f a mobile, inapprehensible and ever changing world, pulling us in its tangled and uncontrollable trail towards a neon twilight and a silent turbid winter.

In 1993, the Spaniards Rafael Moneo and Santiago Calatrava finished their first American works, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College; and the BCE Place shopping mall in Toronto.