It was to be a year of commemorations, but ended up as one of commotions. Hurricane Mitch in Central America and economic catastrophe in Russia mark the dramatic profile of a year that had its comedy of manners in the White House and a summer jolt in the stock exchange roller coaster, while the sentence of British lords against Pinochet raised hopes for globalized justice in a world that has begun to cauterize open wounds in Palestine, Ireland and the Basque Country. Nevertheless, neither meteorological nor political turbulences prevented architects, poets, regenerationists and revisionists from celebrating the centenaries of Alvar Aalto, García Lorca, ‘98 and Philip II. The carrousel of festivities began in Stockholm, incumbent cultural capital, with Rafael Moneo’s Museum. It continued at the Lisbon Expo with the pavilion designed by Álvaro Siza, who also capped Japan’s Praemium Imperiale on the year of Portuguese literature’s first Nobel, José Saramago. There was a moment of multicultural media fervor in Paris on account of the World Cup, staged in the stadium built by MRZC. And the party culminated in a Berlin that reinvents itself to assume German and European leadership. If the architectural year were to be summed up in a telegram, each season would start with a capital letter: winter would belong to Aalto; spring and summer, to Renzo Piano and Peter Zumthor, winners of the two most coveted awards, the Pritzker and the Carlsberg; and autumn to a red-green Berlin that struggles with the burden of memory.

A Nordic Winter

Winter nights whitened in remembrance of the great Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, the centenary of whose birth was celebrated in February through a major exhibition at New York’s MoMA. But winter also witnessed the opening of two new art institutions in Scandinavian capitals: the Museum of Modern Art and Architecture in Stockholm, a work of the Spanish Rafael Moneo on Skeppsholmen Island whose pyramidal skylights emblematized the city’s turn as European culture capital; and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, built by the American Steven Holl beside the Finnish master’s Finlandia Hall, and whose warped shapes invited both praise and controversy.

During the winter, exhibitions like that of the MoMA in New York commemorated the centenary of the birth of the Finnish master Alvar Aalto.

The Spring of Technology

The awarding of the Pritzker Prize to the Genoese Renzo Piano in the month of April was an acknowledgment of technological imagination on the part of a prestigious foundation that had always given preference to more explicitly artistic or intellectual careers. In the course of the year the Italian architect also completed France’s last presidential grand projet, the Kanak cultural center in New Caledonia, demonstrating the same vitality that characterizes those colleagues of his who share an engineering- oriented passion for the large scale: the French Jean Nouvel, who returned to the foreground of architectural debate with a monumental convention center on the banks of Lake Lucerne; the British Norman Foster, who finished the colossal airport of Chek-Lap-Kok in Hong Kong; and the Valencian Santiago Calatrava, who terminated the sculptural Orient Station close to Lisbon’s Expo. Foster and Calatrava, incidentally, have often crossed paths, and this year it was in the hometown of the latter, where the first has carried out a congress center and the second continues the construction of the spectacular City of Sciences.

In spring, the Pritzker Prize recognized the technical imagination of the Genoese Renzo Piano, whose engineering passion is illustrated by the huge scale of the Kanak Cultural Center in New Caledonia.

Summer in the Alps

The Swiss Peter Zumthor received the Carlsberg Prize early in September, and the significant amount accompanying this generous distinction served to popularize a cult architect who practices his craft in a remote Alpine valley with artisan refinement and musical elegance. The author of the Thermal Baths of Vals and the Kunsthaus of Bregenz is but the most veteran of an entire Helvetian generation that has made of matter its artistic religion, and whose most cosmopolitan representatives are the Basel-based Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Previously victors in the competition for London’s new Tate Gallery and finalists for the extension of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the partners have now won their first Spanish commission, the refurbishing of the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The year also saw the completion of their first American work, an extraordinary prism of basaltic stones in steel baskets containing a winery in California’s Napa Valley.

In the summer, the Carlsberg Prize added to the popularization of the Swiss Peter Zumthor, already converted into a cult figure by works like the Vals thermal baths, which illustrate his devotion to materials.

Autumn in Berlin

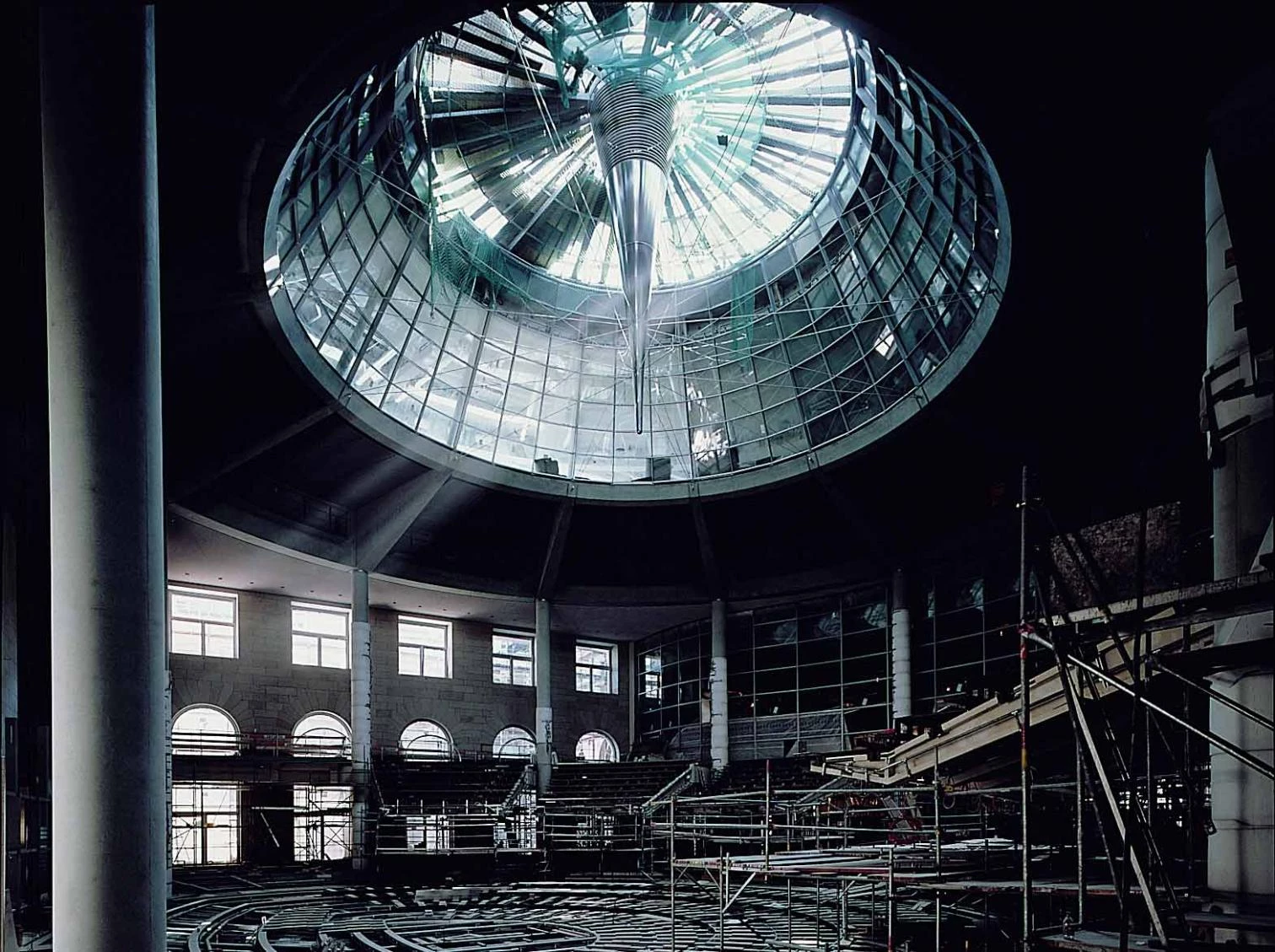

The closing season of the year began with German elections, which as usual were a plebiscite on both the future and the past, two tenses which overlap in Berlin’s troubled present. What prevailed was the social democrat option, which, in tune with other European ‘third ways’, prefer administration to remembrance, shirking the mortgage of ominous memories that end up being little more than theme parks of the Holocaust. Thus the capital of Germany continues to rise up, without respite or prejudices, and the termination of Piano’s brick tower or Moneo’s hotel and offices on Potsdamer Platz are minor anecdotes in a horizon that bristles with cranes and which only takes on a symbolic dimension in the Reichstag, where Foster has already laid the glass dome over the hall where the newly elected parliament is to convene.

The autumn began with a German general election where the nation’s past was discussed as much as its future; two tenses which coexist within the reconstruction project of the Reichstag, undertaken by Norman Foster.

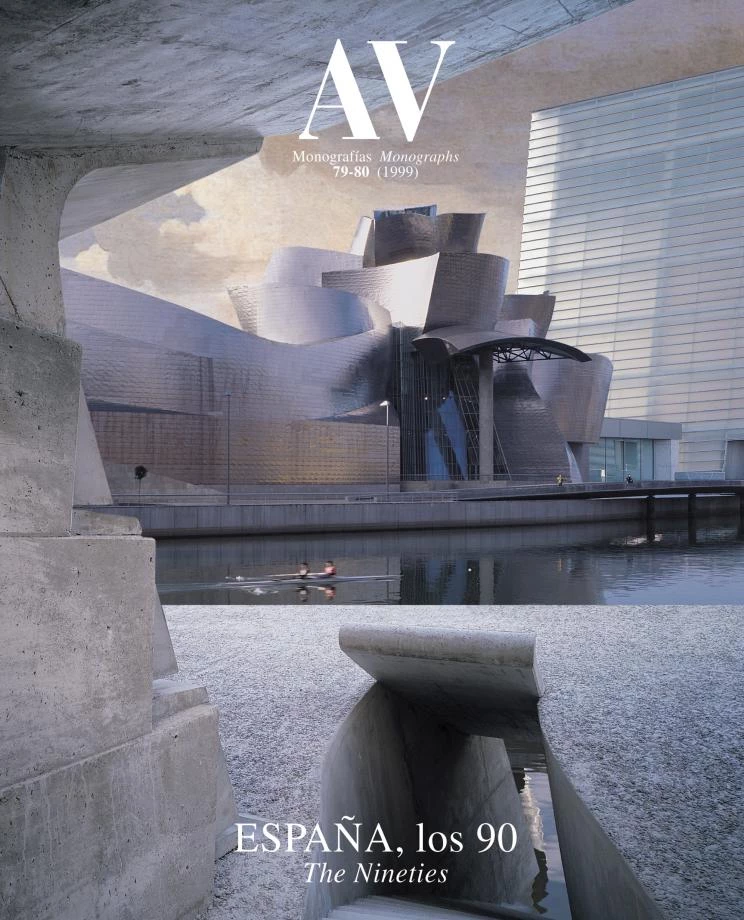

Meanwhile, European architects remain fascinated by Dutch hypermodernity, a panorama of fertile innovations that contrasts with America’s commercial routine and Asia’s impasse. As a laboratory for experiments addressing density and congestion, however, it is of little relevance in geographical zones such as Latin America and the Islamic world, whose peculiar features were presented this year on Spanish territory through events like the Biennial of Ibero-American Architecture, held in Madrid, and the Aga Khan Awards, which were bestowed in Granada’s Alhambra. Halfway between these architectural landscapes, Spain has followed its course at cruising speed, randomly amalgamating the cosmopolitan and the traditional in a panorama that juxtaposes Enric Miralles’ brilliant triumph in the competition for the new Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh with Rafael Moneo’s eventual preponderance in the third round of the Prado Museum contest, and that it is as ready to accept Madrid’s futuristic project for underground highways, as Barcelona’s fervent campaign for the beatification of Antoni Gaudí. We will have to commend ourselves to the Catalan architect when he joins the ranks of saints.