The century is slow to die. Stabbed in Berlin and gored in Sarajevo, this dismal animal bows his head amid vomits of blood and atrocious fits. The butchery slime of the Great War did away with its predecessor in the bullring, a maroon and reticent 19th century, excessive in weight and short of limb. The dark and beautiful beast of our century hesitated in the deep threshold of the corrals, charged during the first round with the tapered horns of the avant-garde, warded off totalitarian picador lances with bravado, and survived the chastisement ready for a long and ornate series of passes, ready for the kill. At the last trance, the breed turns around to face the sword, the animal resists death, and the coming century waits in the gray shadows of the bull pen.

A time of transition and agony, the nineties are turbid and ashen, bad for calm and memory, unworthy of affection and perhaps even of remembrance. Modem architecture, a contemporary of the century, was passionately invented at its dawn. Suffering continual revision, distortion and mutation, it has stayed on stagnant for too long. In its last hours, mannerist and weary, it has rehearsed ironies and faked fractures, to finally return to its original abstraction in a rhetorical cycle that is more reiterative than vicious.

Geometric Certitudes

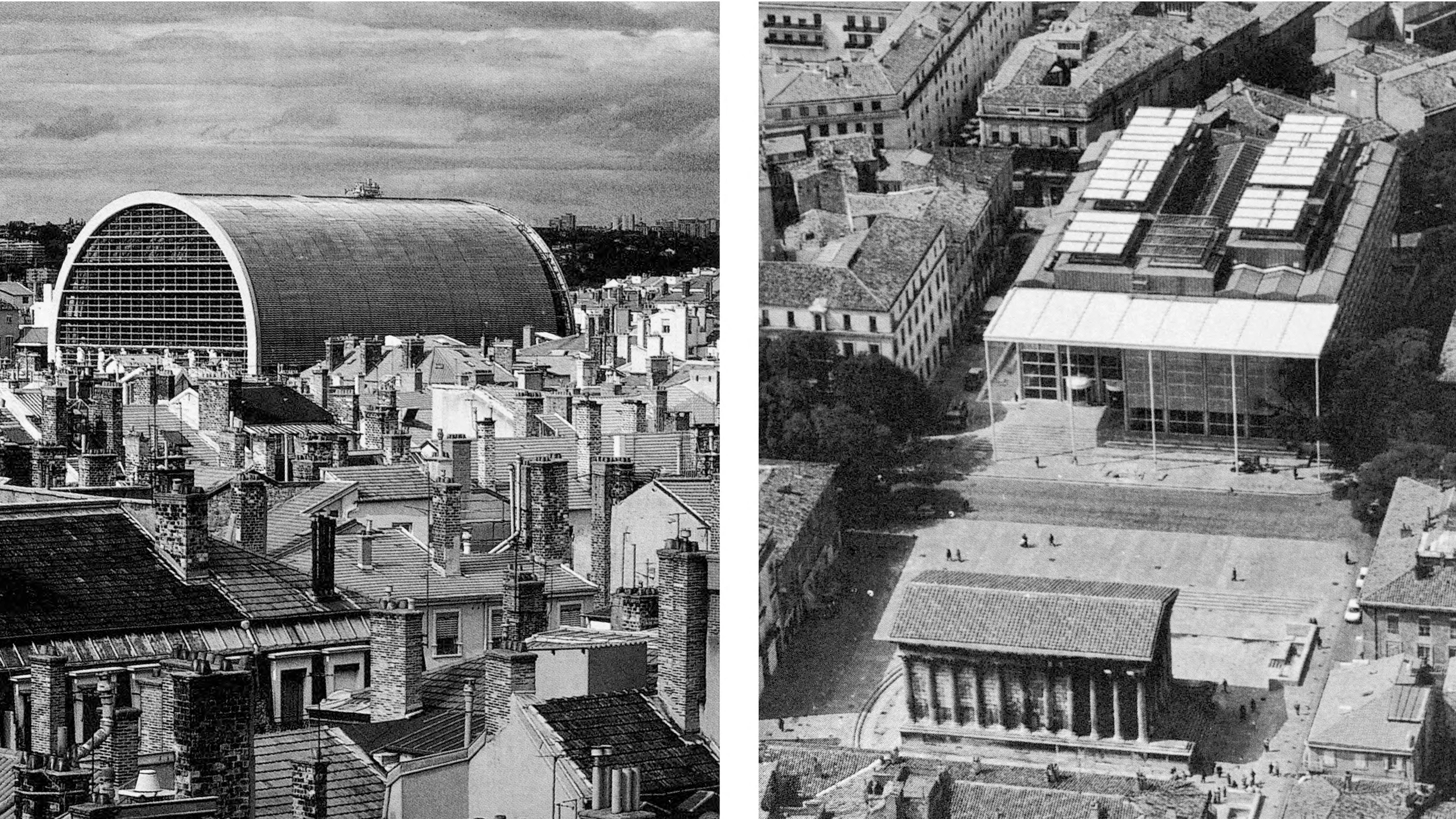

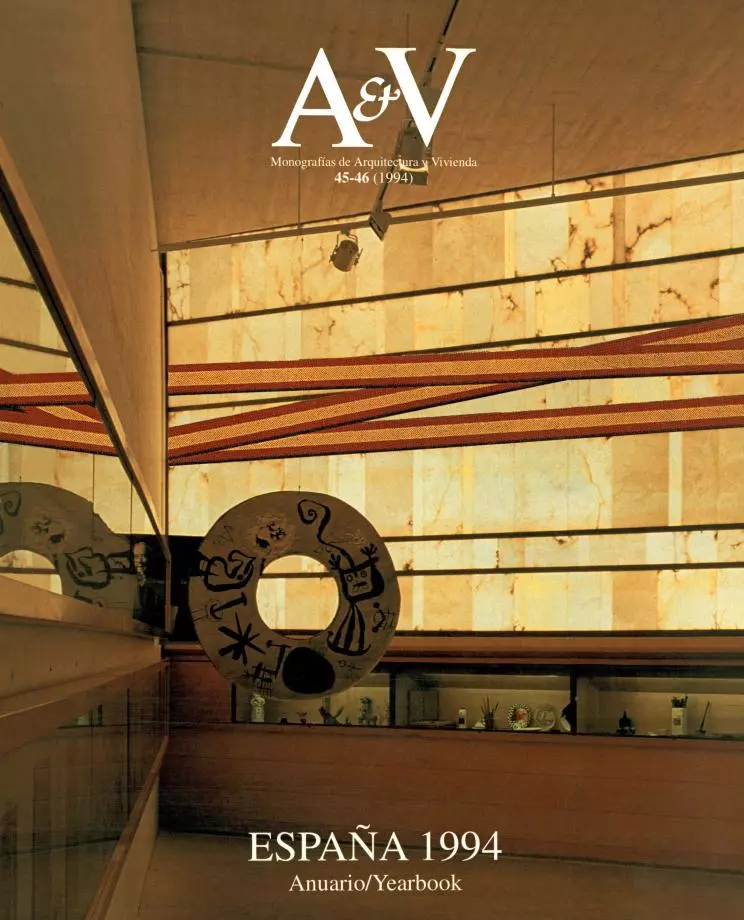

Over the old roofs of Europe rise huge intrepid vaults, cathedrals for the spectacle of culture, beached transatlantics o f a media cult, technological temples of the modem promise. In the clashing juxtapositions of Lyon and Nimes, Jean Nouve’s new opera house and Norman Foster's media library face up to historic memory with elegant determination: one crowns the preexisting building with an impeccable half-barrel; the other confronts the Maison Carrée with a glass prism and a slender metal portico.

The geometric certitudes of modem tradition give classical aplomb and forceful monumentality to these constructions, abstract and arrogant, surviving and foreboding, testimonies of the cyclical return of the heroic elementalism of enlightened reason, which makes an unexpected and insolent comeback at a time of confusion and disbelief.

Within the international panorama, 1993 has seen the realization of important works in the modem spirit, like the Lyon Opera House, by Jean Nouvel, and the Media Library in Nimes, by Norman Foster. In turn, some intellectuals of architecture have expressed the fractures of this ending century, in works like the Kunsthal of Rotterdam, by Rem Koolhaas, or the Columbus Center in Ohio, by Peter Eisenman.

Introverted Levity

But the futuristic imagery of these space containers, also present in Renzo Piano’s metallic mollusks or Fumihiko Maki’s exfoliated and radiant helmets - which evokes the dreams drawn by the avant-garde of the start of the century as well as the technological optimism of the sixties - has a curiously misleading and seductive effect. In their untimely arrival into the century, their introverted levity rises like a dramatic fiction on the tragic stage of our era, deriving its beauty from the contrast with the everyday landscape. As temples with empty altars, they suggest an obstinate and virtuous cycle that orbits obsessively in a firmament of trivial certitudes.

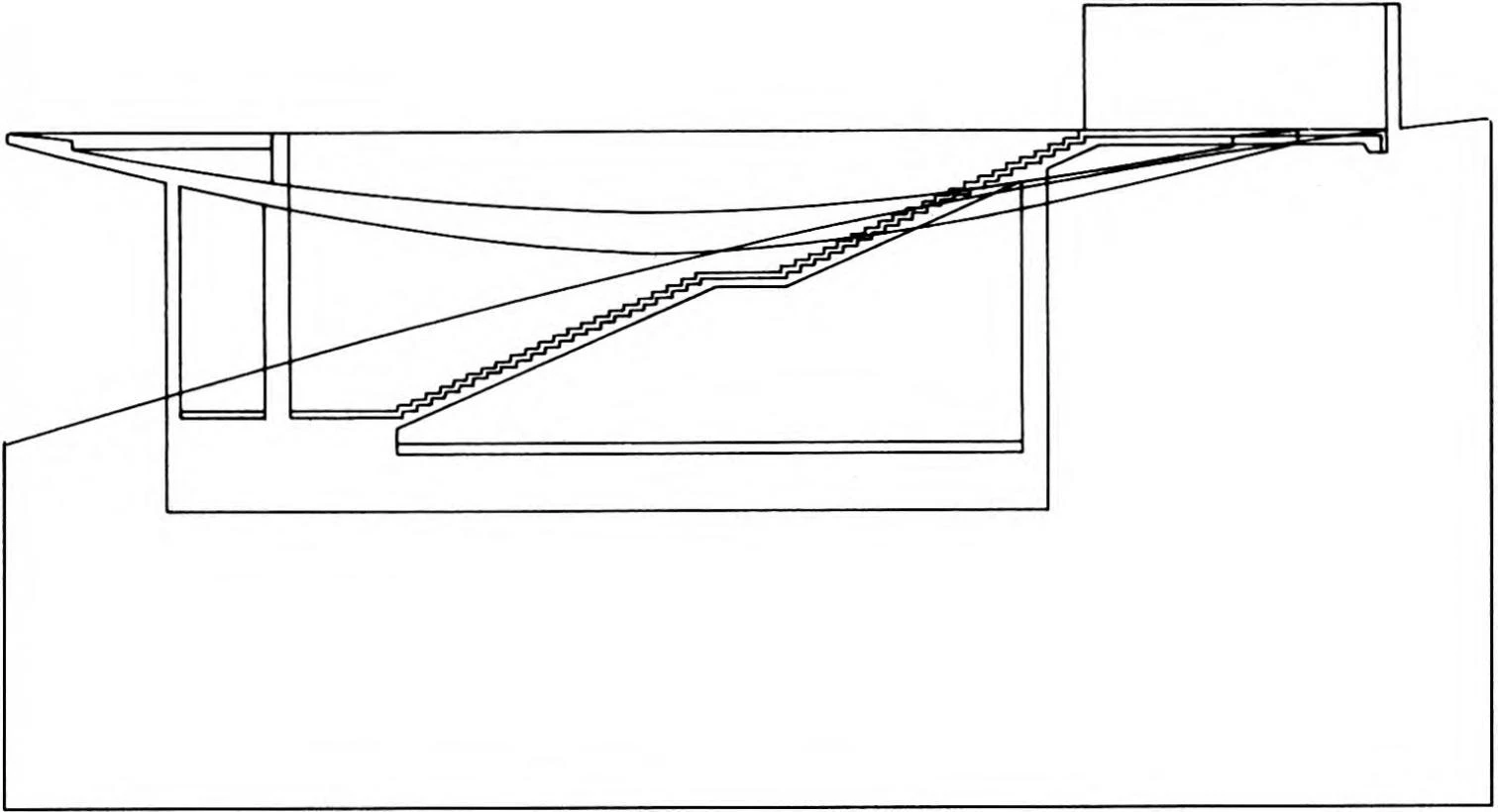

In the existential shipwreck of the fin de siècle, the sacred dimension returns through roads that are more emotional than intellectual. James Ingo Freed’s Holocaust Memorial strikes our gaze with the figurative artillery of the worn out postmodern rhetoric in an unrestrained assault on sentiment; and in Tadao Ando’s Water Temple one descends, beneath a pool of lotuses, to the warm womb of an inflamed sanctuary, through a sudden staircase of theatrical efficiency. Religious architecture stirs the emotion with archaic scenographies and represents horror or serenity with similar instruments of the imagination.

Arbitrary Fractures

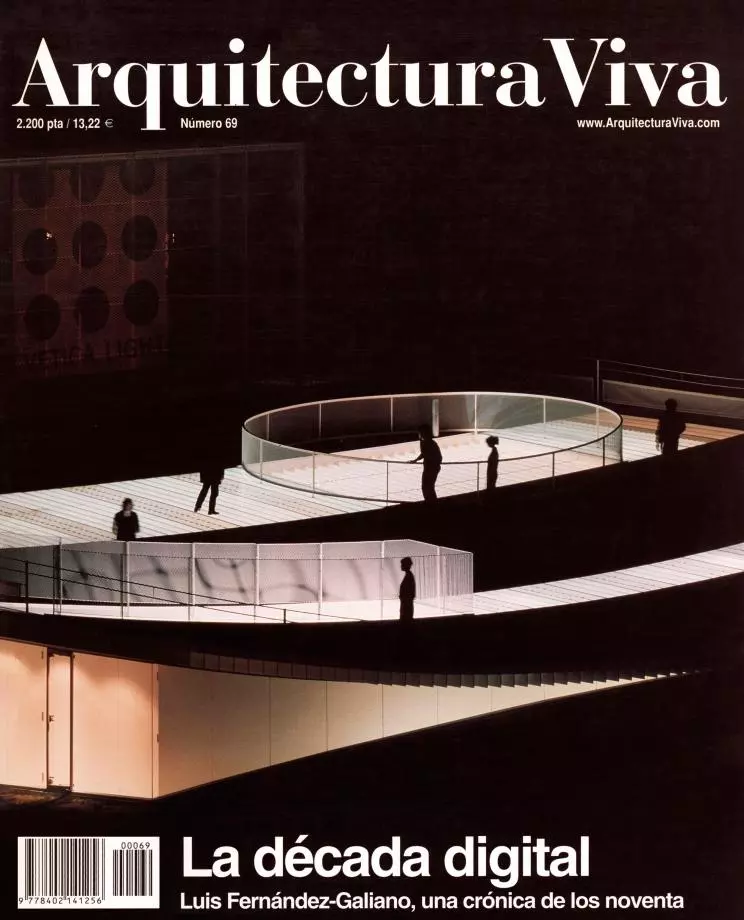

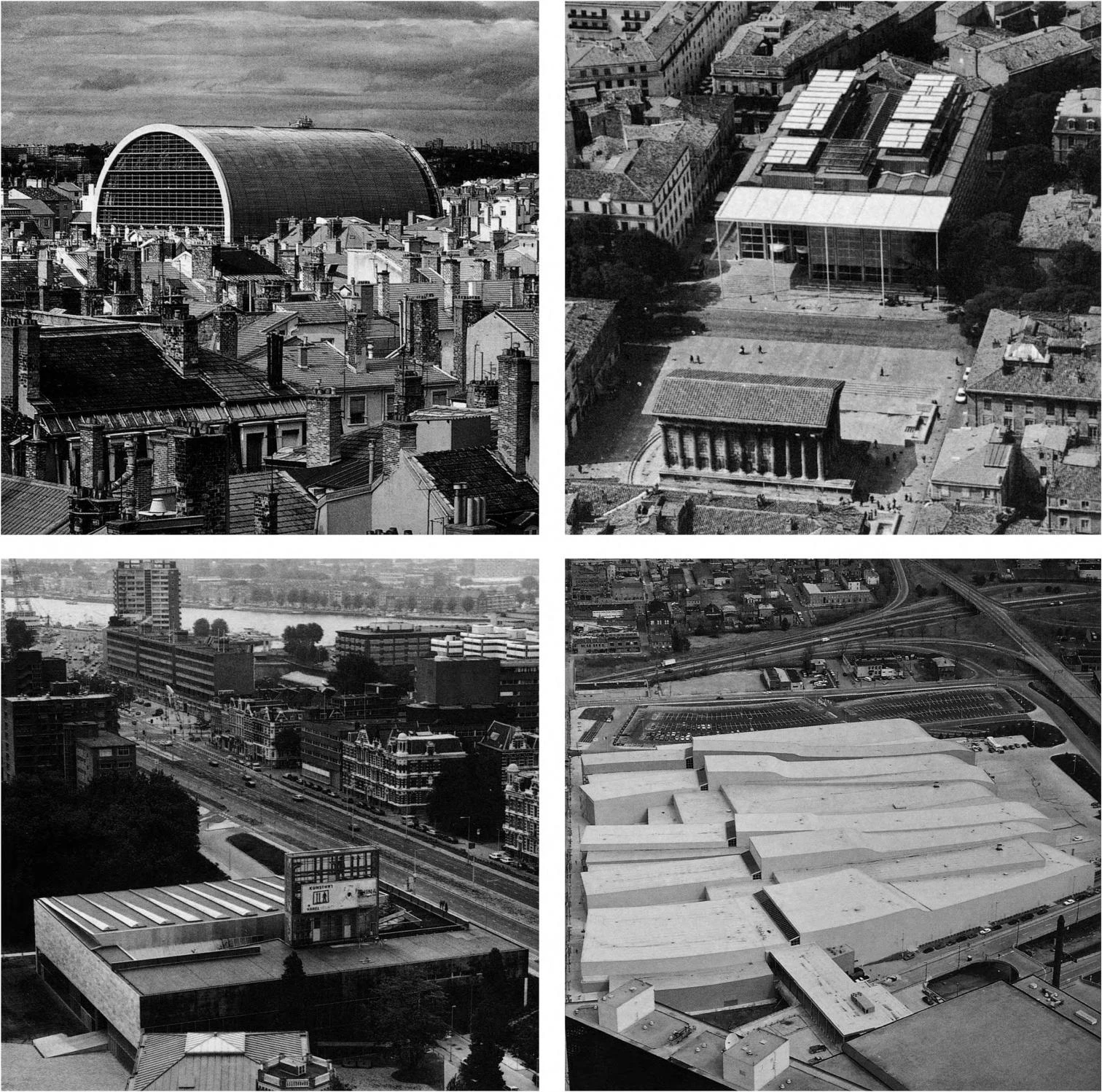

Architecture’s intellectuals strive to give shape to the fractures of the century, and Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam or Peter Eisenman at Columbus feign consternation and arbitrary cracks. The four facades of the Dutch Kunsthal shift in color and material, not so much to defer to its four vicinities as to formulate an ingenious statement; the unitary volume of the American convention center fragments into undulating bands o f a pastel color, and the architect takes pride in the nausea that the dizzying building produces in its users. As can be seen, even the most caustic polemicists end up telling jokes from the repertoire of the fifties or jesting with the pleasant palette of children’s linen.

Though far from the silent and autistic perfection of extreme minimalism, the hyperactive verbosity of these comedies of intrigue reveals the same malaise. As faded grandchildren of Dadaist provocation or the underground pulsations of surrealism, the trampled and brilliant dialogues of communicative hysteria reveal an insomniac anxiety. The agglomeration of gestures, voice inflections, winks and mentions excite and stun to the point of blurring the gaze. In the final analysis, the compulsive neurosis that leads to the torrential heaping of signs is identical to the mute stripping that leads to self-withdrawn, absentminded paralysis; under both circumstances the century is wearing out, exhausted and bewildered.

Sacred architecture continues to use theatrical rhetoric, whether figurative or abstract, in works like the Holocaust Memorial in Washington, by James Ingo Freed, or the Water Temple in Hyogo, Japan, by Tadao Ando.

Landscape in Motion

While awaiting the annunciation of new times, architecture accelerates aimlessly. Zaha Hadid’s diagonal explosions and Alvaro Siza’s pliant implosions compete with Frank Gehry’s scaly inflorescences or Santiago Calatrava’s swift bones in order to represent a landscape in motion, a suspension of memory, brutal and delicate, o f a turbid violence and fugacious beauty. And the cruel ceremonies of the end of the century are held in this convulsive bullring.

Here, the participants toil without fervor, headed for the slaughterhouse or the infirmary of rubber sheets and chloroform, and an anonymous animal awaits its turn motionless in the dark labyrinth of the pens. But while the new century does not alight in the threshold of its dawn, the sullen corridors of the ring will conserve the enigma of its rosette, and the opaque gaze of the onlookers will continue to watch with indifference the final gasps of this rough surly bull.