The future is amorphous. If we are to believe the architects of the latest generation, the constructions to come belong to the formless domains of nature: to geology, not in its ordered and crystallographic version, but its abrupt side of rock and aerolite; to botany, not in its geometrical and floral manifestation, but its subterranean expression as tuber and rhizome; to zoology, not in its logarhythmic shells or symmetrical skeletons, but its random amebas or labyrinthian entrails. Besides machines, the modern masters admired all that which in the universe reveals a mathematical law: the elliptical orbits of the planets and the hexagonal structure of snow, the impeccable helix of the pine cone and the perfect spiral of the snail. In contrast, the new architects abhor Newton and adhere to Freud, opting for the bubbling of magmatic flows, adopting the flaccid shapes of overripe fruits, and exploring the sinuous conduits of organic caves. Spongy or embryonic, this Cambrian explosion of invertebrate and swelling shapes comes of course from a naïf futurism halfway between Barbarella and Alien, but even more so from the capricious versatility of the computer-aided drawing, the true midwife of all this amorphological proliferation.

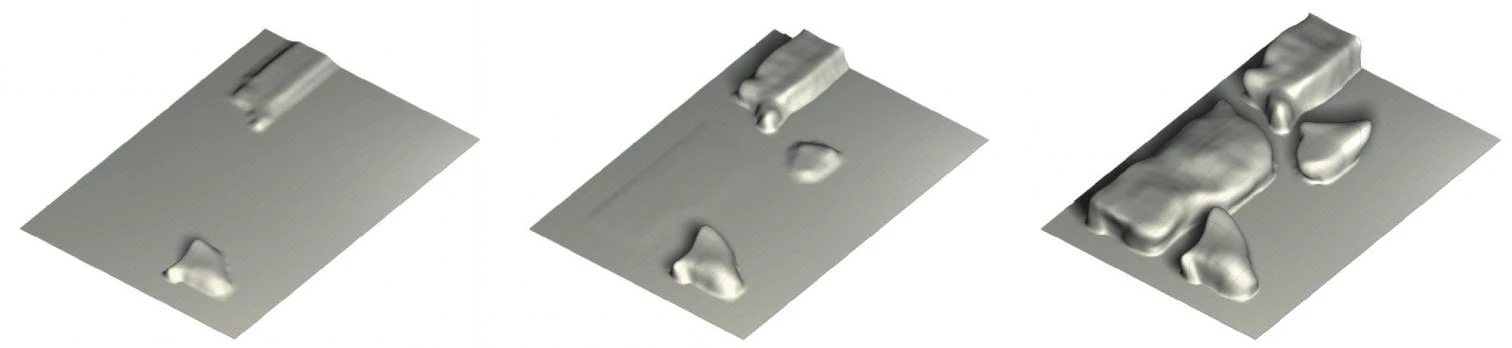

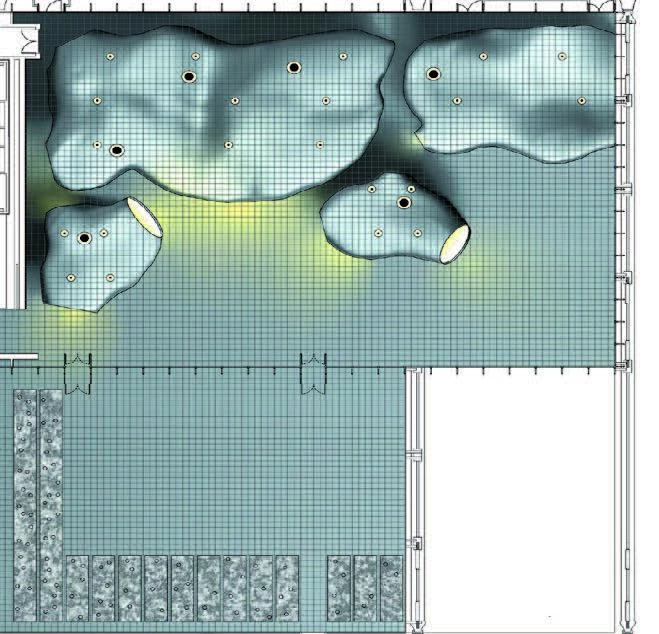

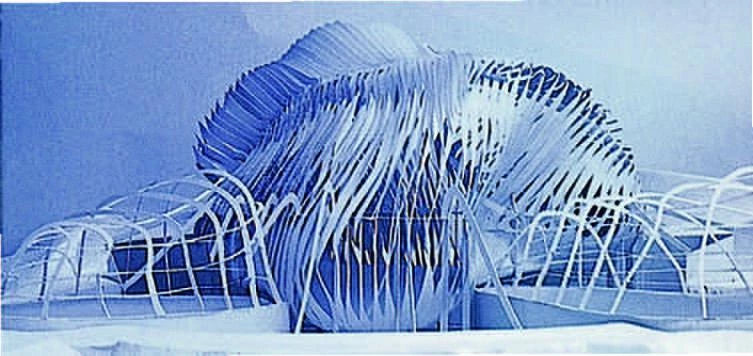

Designed by Jakob & MacFarlane and built in shipyards, the aluminum shells of the new restaurant at the Centre Pompidou are the product of the most recent architectural harvest of blobs and bubbles.

Today, indeed, the astral signs are favorable to potatoes. After the hail of aerolites in the Iberian Peninsula, which filled the refrigerators of the National Meteorological Institute and the Scientific Research Council with tubers of ice, St. Valentine’s Day witnessed the success of the space probe Near in its amorous date with the asteroid Eros, a petrous potato the size of La Gomera island. Such conjunction of signs makes us think that the time is ripe for a planetwide promotion of the artistic tubers that proliferated in the informal fifties, from the sculptures of Arp and Miró to the architectures of Kiesler and Bloc. Now represented with the infinite meticulousness and perfect plausibility of the coputer, this choral harvest of inhabitable bulks forms the flabby flank of contemporary architecture, and to date it has revealed more mediatic aptitudes than nutritive virtues. But maybe no one has seriously thought of these tubers as food alternatives, and their mission is really to ellicit a smile.

Thirty years ago, with the Pompidou Center, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers predicted a different future, one of happy machines on whose colorful scenarios a new playful and amiable culture was to emerge. Today, after a thorough renovation that has cost $80 million, amid the huge tubes and steel trusses of the old industrial Pompidou appear the shapeless bulges of a new, warped architecture. Although Piano and Rogers oversaw the project – which the center’s management altered significantly, to be sure, by introducing escalators and elevators inside the building, thereby disrupting the diaphanous floors and occasioning the impopular decision to charge a fee for the use of the facade’s famous panoramic stairs – the top-floor restaurant was entrusted to Dominique Jakob and Brendan MacFarlane. To differentiate it from the rest of the building, these young Parisian architects built in the shipyards of La Rochelle a collection of tubercular aluminum shells containing kitchens, toilets, cloak-rooms and private rooms, which appear at the heart of the machine like tumors or phantoms. By coincidence, Jakob and MacFarlane are today 33 and 37, exactly like their predecessors Piano and Rogers when they undertook the Pompidou, so it seems right to associate the generational succession with the stylistic mutation.

Computer-aided drawing has delivered a new generation of formless architectures, very few of which have actually been materialized as that of the restaurant at the Centre Pompidou (below).

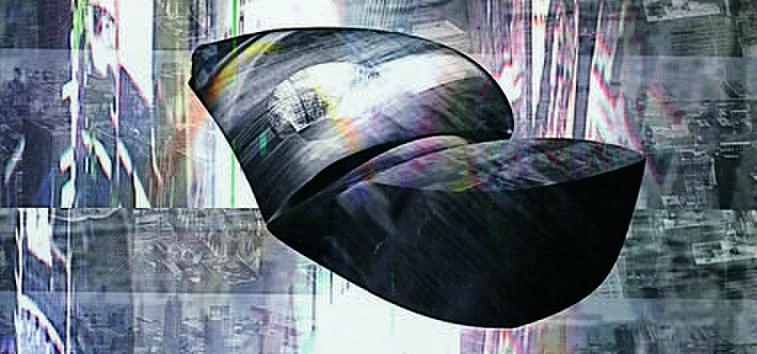

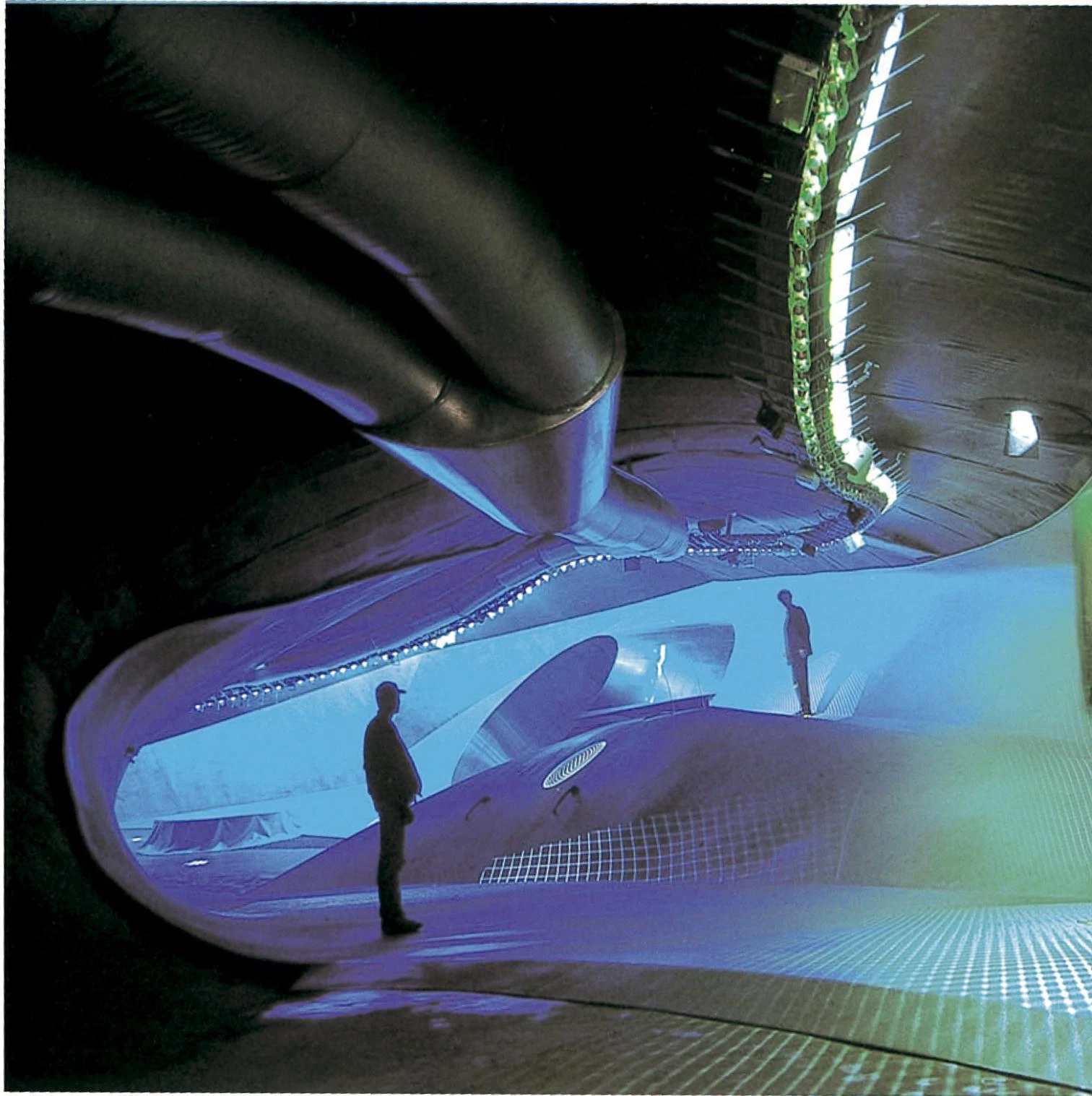

Below, the projects for a technological museum and an embryological house by the Americans Asymptote and Greg Lynn (right); and the H2O Pavilion erected by the Dutch studio NOX (below).

At the same time that the Pompidou was reopening, the American magazine Architectural Record published its millenium issue, featuring 21st-century projects expressly commissioned to nine young firms of the United States, and a crop of forms uniquely resembling the bulbous rhizomes of the Parisian restaurant: cellular inflorescences, bulging viscera and metallic slugs enthusiastically hailed by publishers, who find in the electronic image the scene of a creative digital revolution capable of colonizing the continent of architecture with a neo-Baroque and biomorphic expressionism, “rivaling Borromini and Mendelsohn in experimental daring” in order to design “a high-voltage megaworld.” Unfortunately, like their European counterparts (mostly Dutch, from the NOX of Lars Spuybroek to Kas Oosterhuis, and as fond of the recreational use of computers as their American colleagues), the greater part of the authors (Greg Lynn, Michael Sorkin, Kolatan/MacDonald, Reiser& Umemoto or Hani Raschid and Lise Anne Couture’s Asymptote Architecture studio) have had little opportunity to put their ideas to practice, beyond the occasional exhibition pavilion, the artsy loft remodeling, or the small testimonial construction, which makes it difficult for now to fully assess the result of their contribution.

The modern movement of course began in a similarly precarious way, so it seems risky to deny a future to these extravagant forms, generated on computer screens as virtual germs of a spatial mutation, and which architects trained in the severe discipline of the straight angle can only contemplate as morbid viruses or body-snatchers. Anglo-Saxons like to say “boxes and blobs” to refer to the two dominant currents of young architecture, the minimalist and the formless. But whereas the laconic boxes arouse only some caution toward the dogmatism that goes with youth, the formless blobs provoke the alarmed and perplexed disquietude one feels when watching the paranormal phenomena of The X-Files. Nevertheless this new architecture pursues entertainment, more than specters, and its labyrinthian complexity has more to do with game consoles than with the ominous threats of the heinous. Optimistic in a way, individualistic in its bulging anatomy, and antiurban in its rejection of party-wall compatibility, bubbling, virtual and inapprehensible, the new architecture has something in common with the new economy: born in garages, for many it is nothing but smoke and mirrors, but meanwhile, its value in the Stock Market exceeds any reasonable forecast. As in the case of technological stocks, perhaps formless architecture should have its own Nasdaq.