Field of Stars

Crisis and Uncertainty in the Year of Miró

This year cannot be summed up with joy, but must be closed with hope. In the all too habitual cataclysm of horror and chaos, optimism encounters constellations of birds and comets. Although the year’s end is conducive to sound and fury, Joan Miró’s centenary tinges 1993 with a lyrical pale shadow that lifts its darkness

One could say that this cruel circular year began with the echoes of a bankruptcy and ended with the voices of another. Then its architectural images would be two sterile monuments to greed and megalomania: the unfinished KIO Towers, eventually sold at auction to the creditors of the Kuwaiti investment group, and PSV’s never built armillary sphere, whose first and only stone cost the syndicate UGT’s housing developer a sum of 1,700 million pesetas. Shoddy in architecture and trivial as engineering works, the leaning towers on Plaza de Castilla and the punctured balloon of the Valdebernardo development symbolize, smack in the nation’s capital, the failure of the financial north and of the cooperative south that were the two souls of the socialists’ modernizing program - a project injured by crises and scandals, but finally salvaged by Felipe González’s charisma in the general elections of June.

Santiago celebrates the Xacobean year with the Galician Center of Contemporary Art by Álvaro Siza (above), and Palma the centenary of Joan Miró with a museum beside the painter’s studio by Rafael Moneo (below).

Fractured Museums

Both downfalls speak of the brusque awakening from a dream that has left empty offices and vanished homes in its wake. When the curtain dropped and the lights went on, the magic disappeared and two other infamous conjurers revealed the miserable state of their bag of tricks: López de Arriortúa, the‘superlópez’ of General Motors and Volkswagen, far from giving his hometown a factory, sacked 9,000 workers in the management of an industrial crisis that has split up Seat, one of the country’s emblem firms; and Mario Conde, the sleek financier who fascinated the generation of hot money, brought down Banesto, one of Spain’s banks, to a dramatic situation that not even its sponsorship of the cyclist Indurain can relieve.

But 1993 was also a Mironian and Xacobean year that made it possible to prolong the festive mood of 92 through exhibitions of the Catalan painter in Madrid, Barcelona and New York, and numerous cultural events in Galicia, with the attendant cosmopolitanization of its architecture. If we chose to zero in on this luminous component of 93, the buildings of the year would not be a pair of slanting offices and a ball of promises, but two white and fractured museums: the Miró Foundation in Palma de Mallorca and the Galician Center of Contemporary Art in Santiago, two exceptional works by two masters at their best: Rafael Moneo and Álvaro Siza.

The star-shaped floor plan of the Miró Foundation, built beside the studio that Sert designed for the painter at Son Abrines, links Moneo’s footsteps to those of his predecessor at Harvard, and manifests his talent for cultural buildings - an expertise already proven in the Madrid palace that houses the Thyssen Collection, which also was news this year on account of the definitive sale of the paintings to Spain. The immaculate volumes of Siza’s museum, in turn, are but the first fruit of a generous disembarkation in Galicia of Spanish and foreign architects who, with their forthcoming presence in Santiago, La Coruña, Vigo or Pontevedra, promise to make Europe’s finisterre a Mecca for pilgrims of architecture - just like the city of Bilbao, which has also embarked on an ambitious renewal program.

Controversy Theater

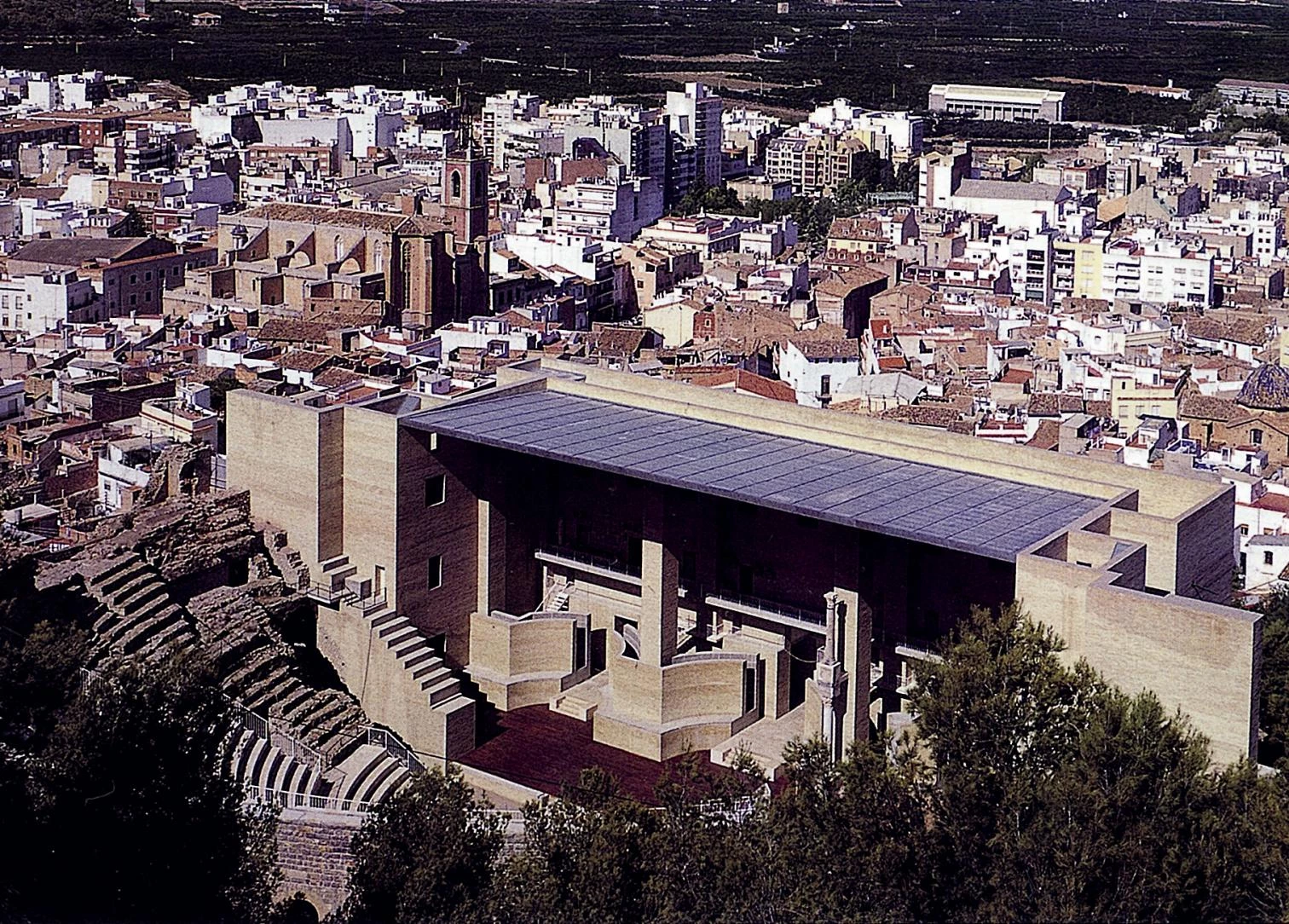

But the year was also a theater of controversies, many of them precisely revolving around architectures of assembly and spectacle. The Roman theater of Sagunto, radically reconstructed by Grassi and Portaceli and subsequently paralyzed by the judges, was the most notorious case; the Sports Center of Huesca, a work of Enric Miralles whose roof caved in in April, the most disturbing alarm for the unstable esthetic of deconstruction. The legal crisis of Sagunto and the physical crisis of Huesca shook the foundations of the profession more forcefully than the expectable esthetic crisis of Madrid Town Hall’s most important work, Bofill’s Convention Center, or the inevitable timeframe crisis of the Royal Theater in the same unfortunate city, where the completion of the Culture Ministry’s pet project has been moved to 1995.

Otherwise it was the year of the Valencian architect Santiago Calatrava, who attained the recognition that comes with being the subject of a one-man exhibition in the sanctuary of New York’s MoMA, an honor in which he had been preceded only by the Catalan Ricardo Bofill - now catapulted to the couché firmament of gossip magazines and the cathodic zenith of trash television, thanks to his son’s marriage to the daughter of Julio Iglesias. The jury of the Prince of Asturias Prize honored architecture in the person of the veteran master Sáenz de Oíza, the first Spanish architect ever to receive the award. And foreign juries singled out our young ones: the Palladio was given to the Madrid partners Beatriz Matos and Alberto Martínez Castillo, and Spanish students, with a total of thirteen prizes, won first place in the Future Bauhaus competition, in which 350 European schools participated. Meanwhile, our administration showed its unconcern or ignorance of architecture through a lamentable professional reform and an even more disconcerting changes in architectural education.

The rehabilitation of the Roman theatre of Sagunto led to the reconstruction of the frons scaenae, reviving the urban role of this landmark, posed between the monumental zone and the city which occupies the hillside.

In the world, the year’s hall of awardees proved notoriously timid, perhaps in tune with the return to a moderate neomodernity after the loss of prestige of postmodern historicism and the scant ingraining of deconstructivist games. For the first time the Pritzker and the UIA medal were capped by the same person, the sensible and eclectic Fumihiko Maki, and the rest of the major trophies went to septuagenarians who had built their masterworks in the sixties: the Praemium Imperiale to Kenzo Tange, the AIA medal to Kevin Roche, and the RIBA’s to Giancarlo De Carlo, all well-deserved but revealing nothing new. Meanwhile, 1993 had its share of illustrious disappearances. In the same year that bid farewell to Don Juan de Borbón, Severo Ochoa and Federico Fellini, architecture lost the Brit Alison Smithson, the Finn Reima Pietilä, the American Charles Moore, and our own endearing Ramón Vázquez Molezún.

Open Wounds

Architecture found its way to the headlines only through the catastrophes or expiatory acts of this violent century, which was born in blood in Sarajevo and now agonizes, in pain and frustration, in the same Bosnian capital. Islamic fundamentalism’s attack on New York’s twin towers in February, the devastation caused by the IRA in London’s City in April, and the burning of the Russian parliament by Yeltsin’s coup d’état in October are all about the ethnic, religious and political conflicts that are ripping the social fabric of cultures and the physical fabric of cities - in a world at once more united by information highways and economic agreements, and more fragmented by racial hatred and linguistic clashes.

Following the stir caused by the partial collapse of the Sports Center in Huesca, Enric Miralles completed his Center of Rhythmic Gymnastics, with a wavy structure which alludes to the surrounding mountains.

Though there were signs of hope, such as the handshake of Arafat and Rabin or the blue ribbon campaign in the Basque Country, the wounds of the world remain open, and religions respond with piety, calculation and impotence. While Muslim temples are torn down in India and Bosnia, King Hassan II has made Casablanca the site of the largest mosque east of Mecca, in an attempt to rechannel the Islamic wave that is sweeping Algeria or Egypt. Cardinal Ovando has given ruined Managua a cathedral, before the eyes of Sandinistas and Protestant sects. And American Jews have funded a Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. that turned out to be the architectural event of the year, comparable only to the cinematographic rage that was raised by Schindler’s List, a post-Jurassic Spielberg’s three emotive hours in black and white about the Jewish genocide.

Everyday holocausts nevertheless persist in a planet devastated by ecological, economic and sanitary catastrophes, which spell out the signs of the new international disorder that this society of malaise had gestated. Still, hope is present in Miró’s constellations, with suns, women, shells and moons; and also in a star of clear green water on the edge of the sea. The sculptor Alberto thought that «the Spanish people has a road that leads to a star.» Maybe this is it.