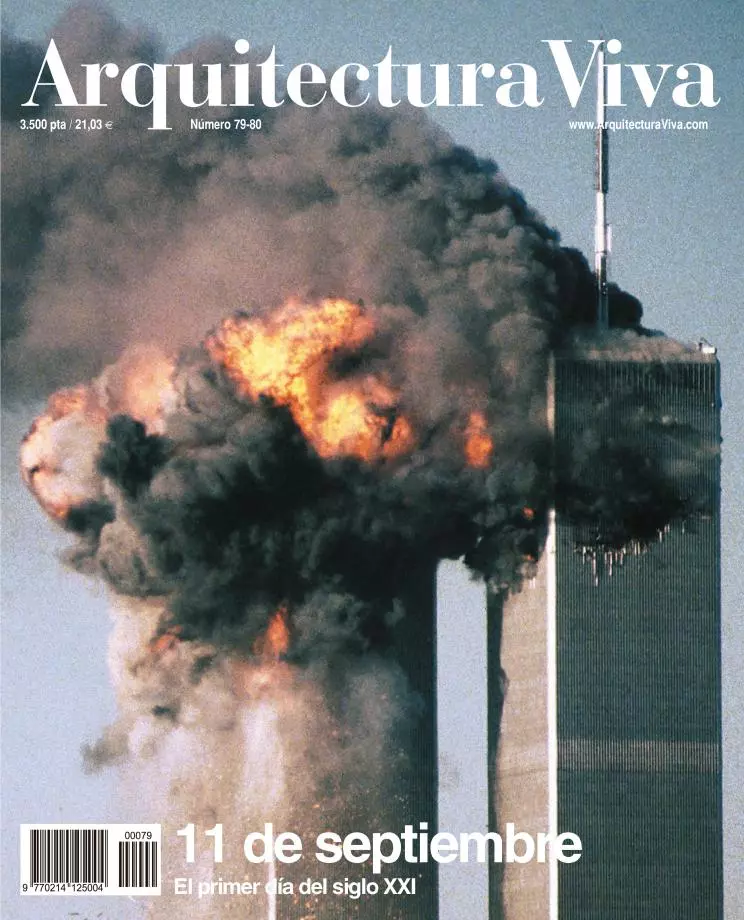

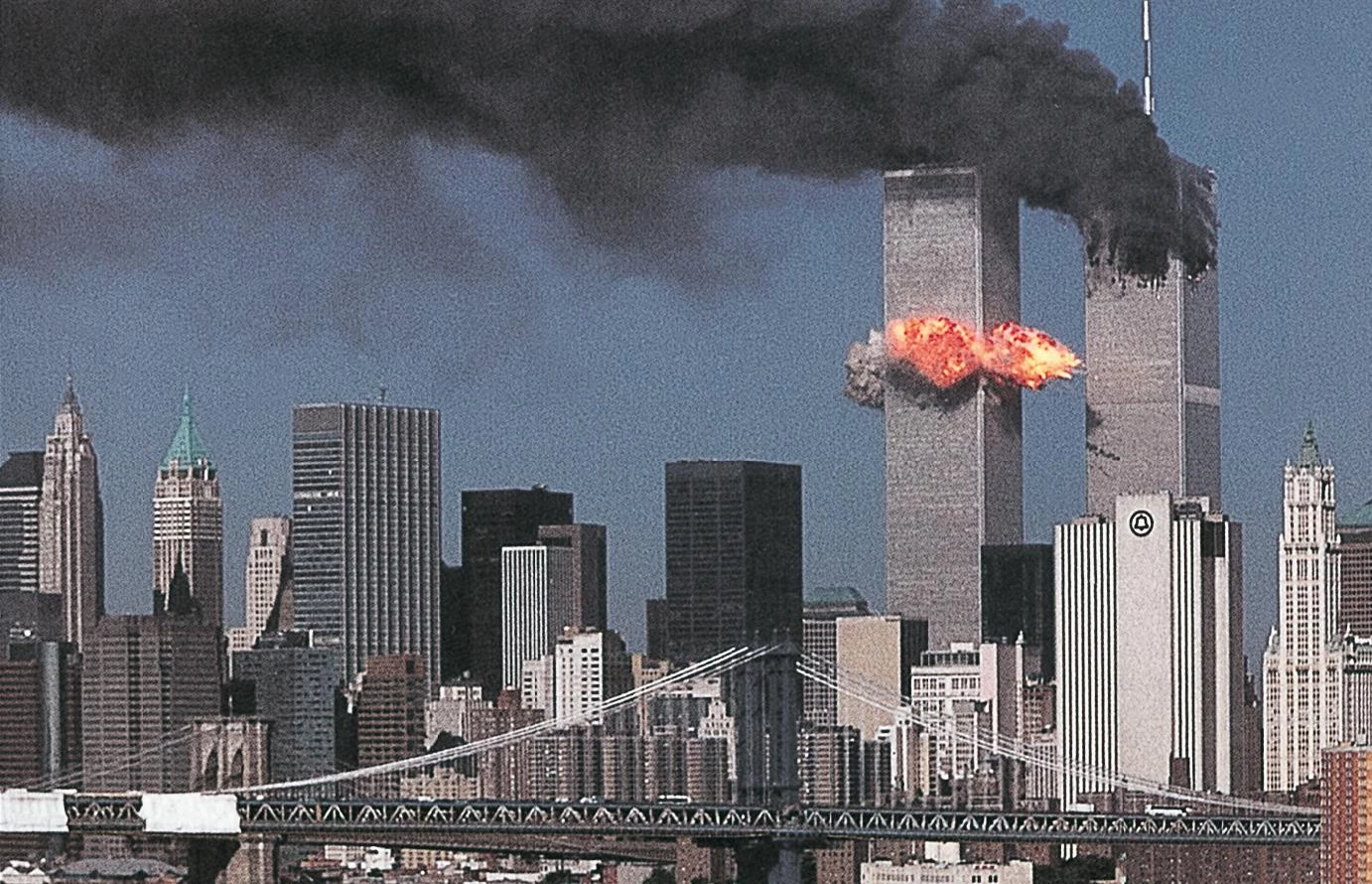

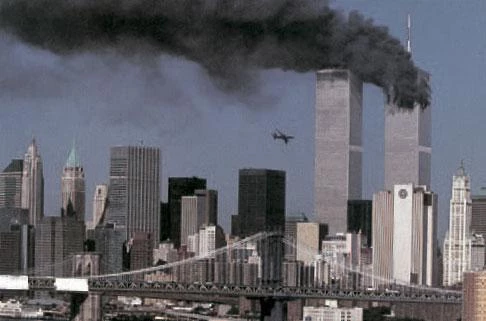

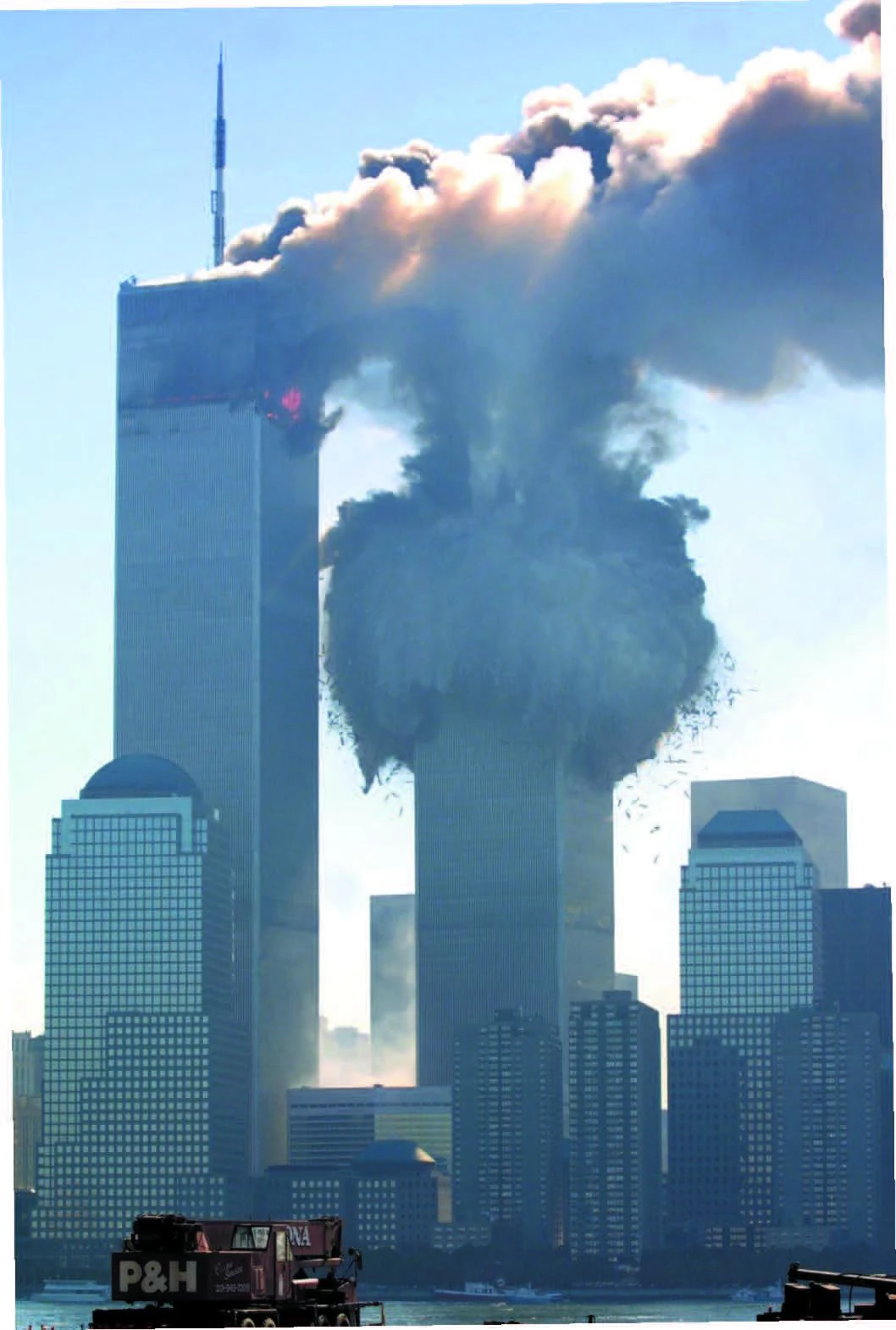

The brutal destruction of the World Trade Center has made us all New Yorkers. Four decades ago, the raising of the Berlin wall provoked a similar wave of fraternal empathy in the face of the threat of urban asphyxia, and the West felt with Berlin: “Ich bin ein Berliner” were the mythical words with which President John F. Kennedy expressed his firm support to the city. Today European leaders proclaim their warm solidarity with the United States, considering the attacks on New York andWashington, D.C. aggressionson humanity.The crime that has severed Manhattan’s skyline has left a tragic count of casualties, but also affects the symbolic horizon of the contemporary world: the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were an emblem of the arrogant power of capitalism and technology, of the economic success of the United States, and of the financial vigor of New York City.

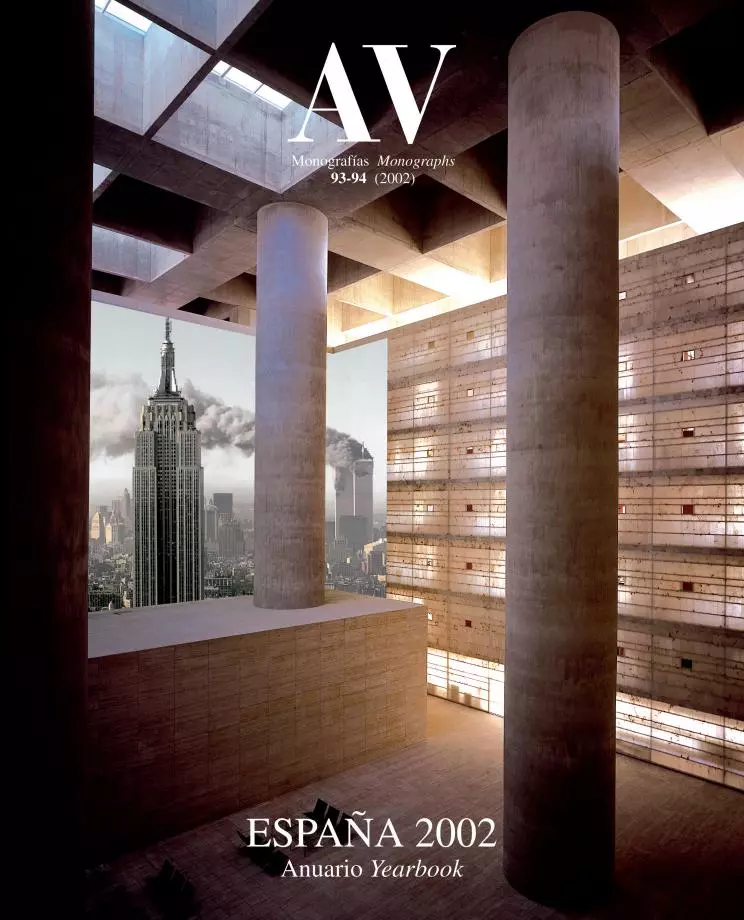

The symbol of the American power was reduced to smoking rubble, in which fragments of the facade latticework designed by Yamasaki recalled the light quality of the twin colossus.

Heirs of Chicago skyscrapers through the abstract interpretation of the German modern master Mies van der Rohe, but prefigured in their prismatic slimness by the project of the Russian Ivan Leonidov for the Narkomtiazhprom (People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry), in the famous 1934 drawing where a tower soars toward a sky dotted with airplanes – Soviets and Americans shared at that time the same innocent faith in progress–, the towers of the nisei Minoru Yamasaki show the influence of two of his successive masters: the architect Wallace K. Harrison, head of a major firm closely connected to New York’s powerful Rockefellers, and the designer Raymond Loewy, creator among other things of the corporate image of United Airlines and the interiors of its planes.

Combining Harrison’s experience in constructing office skyscrapers with Loewy’s lessons in industrial design, and in the wake of the success of his first solo project, a small airport, Yamasaki developed a language of his own based on tight fretworks of painstakingly profiled structural pieces, which evoke the delicate Rudolph of the fifties and give the buildings a Gothic lightness. This is explicit in the pointed arches of the base and crown of the Twin Towers, and in the elegant verticality of their rising nerves; on the other hand, it is rudely tainted with postmodern figuration in his posthumous Madrid work, the Picasso Tower, to which his collaborators added a low arch at the bottom and an Egyptian cyma at the top. In New York, nevertheless, Yamasaki crystallized an admirable and optimistic icon of the 20th-century where the visionary imagination of Leonidov ties in with the entrepreneurial pragmatism of Harrison: two architects who for no small reason have a prominent place in the private pantheon of heroes of Rem Koolhaas, the most eloquent defender of the planet’s architectural and urban Americanization.

Two days before the two Boeing 767 planes crashed into the Twin Towers, Berlin inaugurated the Jewish Museum, a fractured building that evokes the discontinuous presence of an ethnic and religious community in the German capital, including the dramatic segue caused by the Holocaust, another episode of the universal history of infamy. Like the New York hecatomb, the extermination carried out by the Nazis rips the conscience and emotions so intensely that intelligence is hard put to confront the abyssmal evil of the authors, and perhaps only a wordless language like architecture can supply an efficient testimony. It is what the Polish American Daniel Libeskind has done in Berlin, through a violently lyrical construction designed shortly before the fall of the wall in 1989 and opened to the public twelve years after, in ominous coincidence with the American Armageddon.

The symbol of the American power was reduced to smoking rubble, in which fragments of the facade latticework designed by Yamasaki recalled the light quality of the twin colossus.

To be sure, the building in its odyssey underwent no few metamorphoses. Dazzling as a project, the museum was an extraordinary structure even when only the folded screens of concrete rose from the ground. The metal facade and interior cladding finishes took away some of its rotundity, although the 350,000 persons who traversed the empty rooms during the last two years can testify to the evocativeness and enigma of the spaces. And finally it has taken on the character of a Jewish theme park, offering visiting families “the taste of adventure” in its exhibitions (including “Libeskind moments”), the delights of kosher (with Sephardic and Ashkenazi versions), and a whole gamut of objects (with the zigzag imprint) in the book and souvenir store. A sugary transformation, in fact, that has required a redesigning of the museum’s fractured logo, the edges of which seemed too unfriendly for common tastes. It has been softened by inscribing them in the rounded, sweet, refreshing profile of a Biblical pomegranate such as those which would have grown in King Solomon’s orchard.

With the stock exchanges tottering, financial advisers are now rearranging the portfolios of their clients in accordance with their respective capacity or desire for risk, which they tag with four conventional adjectives: daring, determined, prudent, conservative. The cooling of the climate inevitably tempers ardent audacities, making investors step down to conventional refuges, and the Libeskind project’s long haul from the drawing board to theticket office is no exception: daring in the plans, determined on the construction site, prudent in the finishes, and conservative at opening.We have at some point talked about the appropriateness of keeping empty a building that can only speak of horror with silence; but neither the architect nor the critic can do anything in the face of the unanimous and placid power of the themepark craze that turns everything into trivial entertainment.

Designed by Daniel Libeskind shortly before the fall of the Wall in 1989, and inaugurated two days before the 11 September events, the Jewish Museum of Berlin brings back the memory of another tragedy with its broken volumes.

More than a half-century later, the memory of the extermination of six million European Jews hovers over our lives like a light weight that lets it be interwoven with amiable tales of history ad usum delphini. But it survives, intact, in the strategic lines of fracture in the Middle East, and these may just lie in the origins of the abominable attacks on New York and Washington. Now, while firemen still toil in the search for victims in the rubble of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it seems an impertinence to predict that the unbearable pain of the tragedy will ease long before its political, technological and social consequences are extinguished. September 11 pushed us into the terra ignota of the 21st century, and all we know is that it will unfold, for an extended period of time, beneath the elongated and parallel shadows of two absent towers.