The August 1999 issue of Dialogue asked: “Will we ever have a Bilbao in Taiwan?” The Taipei-based journal dedicated its cover to the fractured forms of Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, and printed the question mark of its Forum over a photograph of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim, following a text in which the editor clamored for the implantation on the island of a museum of the likes of Libeskind’s in Berlin, Gehry’s in Bilbao or Zaha Hadid’s in Cincinnati, whose unstable volumes he reckoned are drawing the attention of the public, pulling up tourist demand, and energizing the economies of the corresponding cities. Just a month later, a devastating earthquake caused thousands of deaths, and strewed the cities of Taiwan with broken buildings that in press images could pass for deconstructivist projects, a painful and tragic paradox that prompts a melancholic reflection.

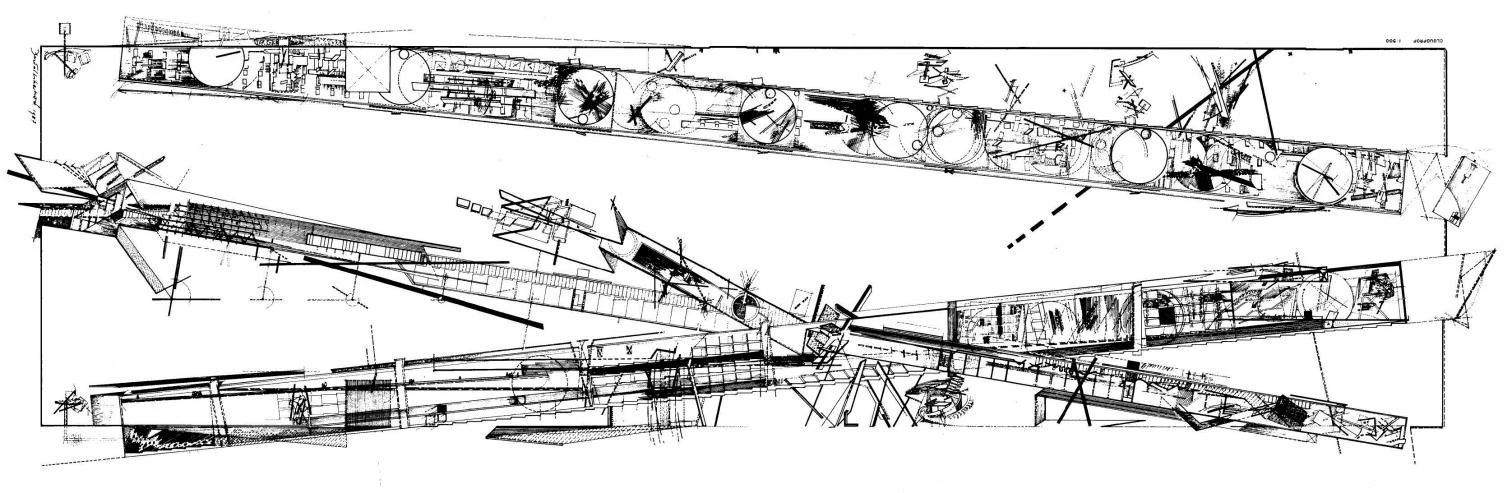

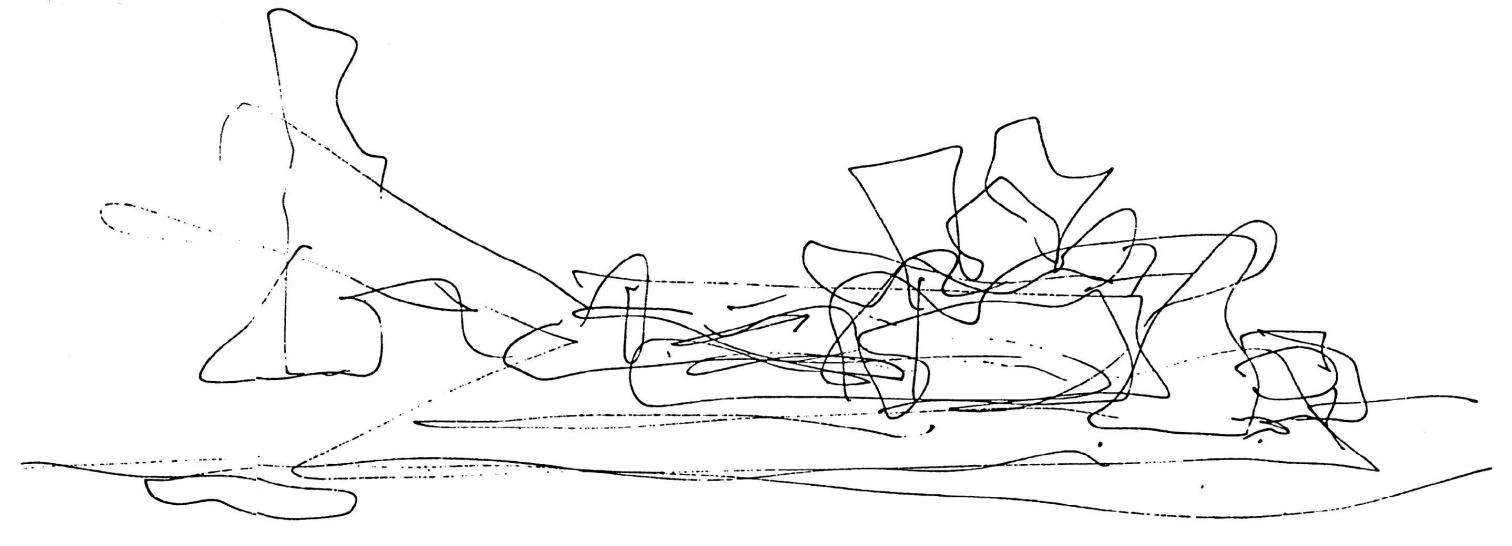

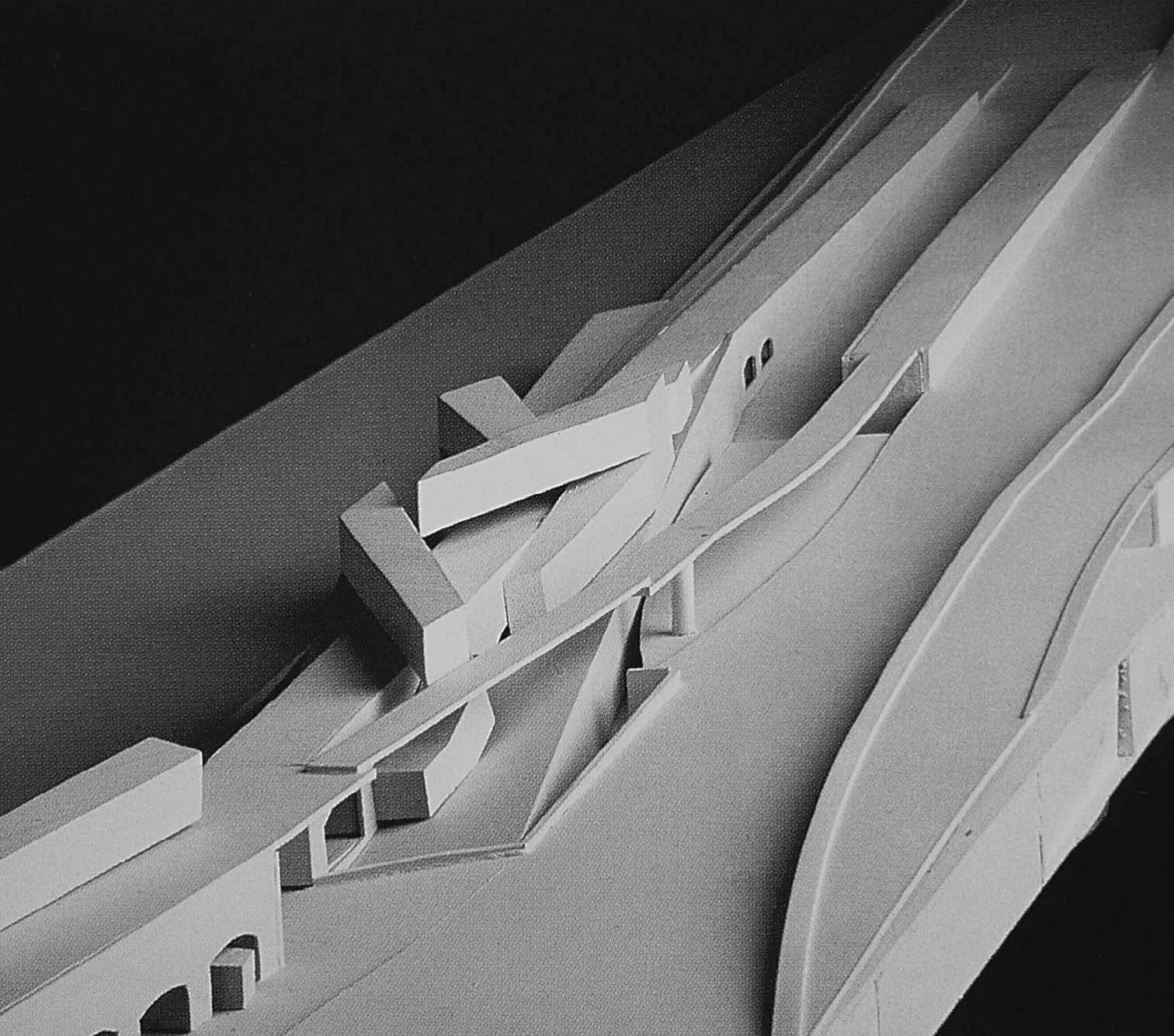

Peter Eisenman: Tokio Model of the Nunotani Headquarters

Earthquake in Taiwan 1999

Earthquake in Kobe, Japan 1995

Peter Eisenman: Hotel in Madrid

The buildings destroyed by recent earthquakes in Asia resound in Peter Eisenman’s gridded drawings or models, as the demolition in Catalonia has echoes in the fractured work of Coop Himmelb(l)au.

Demolition in Barcelona 1999

Coop Himmelb(l)au: Cinema, Dresden

Three years ago, the Venice Biennale di Architettura proposed for its sixth edition the theme The Architect as Seismograph, and Arata Isozaki, responding with caustic irony, dedicated the entire Japanese pavilion – of which he was curator – to the quake that a year before had caused enormous damage in Kobe, near Osaka. Architecture can tremble to express the instability of the times, and architects can feel like seismograph needles vibrating with the convulsions of the Zeitgeist, but when seismic metaphors become real, as they occasionally do, then architecture and architects must repair rather than represent.

The Bengal and Chicago railway catastrophes shake trains to make them resemble the unstable forms of Daniel Libeskind, while the Madrid fire likewise leaves remains as caligraphic as the work of Enric Miralles.

Enric Miralles: Station in Toyama, Japan

Barracks after a fire, Madrid 1992

Train collision in Bengal, India 1999

Daniel Libeskind: Project for the Tiergarten, Berlin

With its unexpected shapes, fractured architecture claims to represent an uncertain world, and to be inspired by new scientific and epistemological paradigms. But when it does not simply try to fare better in the market of images, its purpose seems to be more to exorcize than to portray. The most trivial versions of it feed on the romantic humus of uniqueness to cynically conform to the contemporary society of spectacle, which voraciously demands an abundant supply of novelties. But the most genuine works and authors struggle to explore the construction of physically and visually unstable objects as an antidote to turn-of-century vertigo. Though they pretend to say “this is how things are nowadays, complex and crooked”, the real message is “if we can make these impossible forms stand, so will we manage to keep a fragile world stable.”

Daniel Libeskind: Nussbaum Museum, Osnabrück

Derailment in Chicago 1999

Many of these unusual constructions refer to other episodes of 20th-century architecture, and very particularly to certain movements of the historic avant-garde, including futurism, constructivism and expressionism. Such isms, however, share a visionary mood and a Utopian impetus that is not easily found in these new architectures. El Lissitzky’s horizontal skyscraper does resemble Libeskind’s cantilevered bars, but what in the Russian was optimistic challenge is in the Pole musical perplexity; Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower is echoed in Gehry’s warped surfaces, but what in the German was demiurgic intention is in the Californian formal delight and emotional titillation. Those movements endeavored to open a century that was reluctant to be born; our architectures try to exorcize the closing of a century that is disinclined to die.

The Bengal and Chicago railway catastrophes shake trains to make them resemble the unstable forms of Daniel Libeskind, while the Madrid fire likewise leaves remains as caligraphic as the work of Enric Miralles.

If the avant-gardes emerged in the course of a century that began with the Still Life with Chair Caning of 1912 or the Sarajevo pistol shot of 1914, the unstable architectures that wrapped it up did so at the actual time of its closure, and the emblematic MoMA exhibition on deconstructivism opened in 1988, just a year before the fall of the Berlin wall terminated a short century. The convulsions of the nineties already belong to the century to come, and this ‘digital decade’ that has embodied globalization in the net, opened the floodgate of genetic engineering, and witnessed the social disasters brought about by the planet’s new political tectonics, is not the last decade of the 20th century, but the first of the 21st. And at the threshold of this new era, architecture trembles and contorts itself in order to avert uncertainties and catastrophes.

The blowing up of a housing complex in Chechnya 1999

Frank Gehry: Düsseldorf Office buildings, Düsseldorf

Like a homeopathic medicine which uses minute doses of lethal substances, or like a vaccine that injects debilitated pathogenic germs into the organism, unstable architecture provokes small commotions, controllable fractures and tamed calamities that feign danger through fatal forms and cauterize anxiety through cautious catharsis. Quakes and explosions, train accidents, fires, demolitions, shipwrecks... the line-up of cataclysms that provides models for shaken constructions is interminable, and its constant presence in the media ensures that the message sinks in. When architecture imitates or evokes them, the shudder of risk gets mixed up with the delicious pleasure of peril-free fear, and construction works have the effect of shooing away the diffused panic of the turn-of-the-millennium.

Frank Gehry: Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao

Oil-tankers crash in Malacca 1997

Nevertheless, catastrophic forms frequently justify themselves by invoking the contemporary break of the Newtonian universe and the mechanistic paradigm. Thom’s inevitable catastrophes, Mandelbrot’s fractals and chaos theory –which the more informed set against Prigogine’s dissipative structures, Haken’s synergetics, Eigen’s hypercycles, Jantsch’s self-organization or Bohm’s implied order –merge in a confusing amalgam to shape a formal topography of folds and fractures, Moebius strips and Serpinski cubes, rhizomes and fractals, all of which adorn T-shirts and magazines, students’ rooms and competition entries, designer bars and doctoral theses. Now add to this cocktail of scientific popularization, New Age mysticism and recreational topology a few drops of holistic cosmology, post-structural philosophy or computer-generated warps and the euphoric drink of the new architecture is ready to be served.

Zaha Hadid: Viaduct project in Vienna

Derailment in Guadalajara, Spain 1997

Such naïve inebriation, looked on condescendingly when it comes up in the abstruse texts of the youngest Anglo-Saxon generation, is all the more irritating when found in writings by veteran architects or critics. A case in point is Charles Jencks’s recent book The Architecture of the Jumping Universe, which interprets the works of Gehry, Eisenman, Hadid or Libeskind in cosmocomic terms, threading together a collection of outrageous metaphors that culminate with an image of the Tàpies Foundation in Barcelona, where the artist’s sculpture Núvol i cadira – a tangle of metal which, drawing in space in the manner of Julio González, represents a cloud and a chair – is interpreted as no less than an image of superstrings! The world of architecture has not yet had its Sokal’s Hoax, but it is about time someone came up with a fake such as that elaborated by the American physicist to ridicule and expose the fatal combination of oceanic ignorance and boundless audacity of so many of our critics and theorists.

To explain unsteady constructions, we do not need a mathematical and physical paraphernalia which architects find more difficult to understand than Egyptian hieroglyphics. Suffice it to resharpen critical tools rendered rusty from disuse, but which have served us well for ages. A century and a half ago, Gottfried Semper suggested that architecture be understood as the cladding of a subordinate structure, and this interpretative alternative to tectonic classicism perfectly fits those sculptural constructions that not only avoid revealing the logic of their structures, but even take pleasure in looking unstable. Against the Apollonian culture of serenity and structural composure, the Dionysian architecture of fracture and disobedience builds a disturbingly festive reality that goes back to Nietzsche, but also to the Hittorf who vigorously made up classical temples with shocking polychromies.

Architecture of this kind cannot sin against the truth of its structure, since structure here is but a scaffold holding up a stage. To use Semper’s terminology, the cladding here is not Bekleidung, but Verkleidung: disguise more than dress. The titanium scales of Bilbao’s Guggenheim or Daniel Libeskind’s stainless steel patches in Berlin’s Jewish Museum are the torn, turbulent attrezzo of the century’s final show, and these tatters are the dramatic expression of the Zeitgeist. But just as the Einstein Tower was a better representation of the Angst of the period than the theory of relativity, so are our fractured constructions exorcisms of the catastrophes of our time, rather than illustrations of chaotic or fractal mathematics. Baudelarian after all, in their convulsive beauty dwell the shadows and hopes of a fading century.