The master from Kuortane turns one hundred with unanimous health. After the critical parenthesis of the last stage of his life, Alvar Aalto posthumously recovered the mythical stature he had attained back in the fifties, and lived on to our days canonized as one of the century’s great creators. Nevertheless, the pedestal on which his figure rises has been built with different materials in each period, and it is not easy to guess which wickers will weave his centenary image. Functional and organic Aaltos have taken turns in winning the day, and even a Nordic classicist Aalto was briefly postulated by postmodern historicism. But every anniversary retraces the profile of the protagonist, so it is not out of line to expect the 1998 celebrations to leave yet another Aalto in their wake.

The almost coinciding cen tenaries of Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier a decade ago substantially altered the image of both: the American Mies of glass prisms - in the end the most influential and imitated - lost critical clout to the neoplastic European Mies; the urbanistic and social reformer Corbusier was subordinated to the purist author of white villas, and both were judged to be inferior to the archaic and lyrical builder of his final works. Years later, the major exhibitions on Louis Kahn and Frank Lloyd Wright had a similar readjusting effect on our perception of the two masters: Kahn moved from geometric Roman monumentality to the cabalistic shine of Jewish mysticism, and Wright, from the fertile dialogue with Europe and Japan to American exaltation of the pioneer creed of Emerson or Whitman.

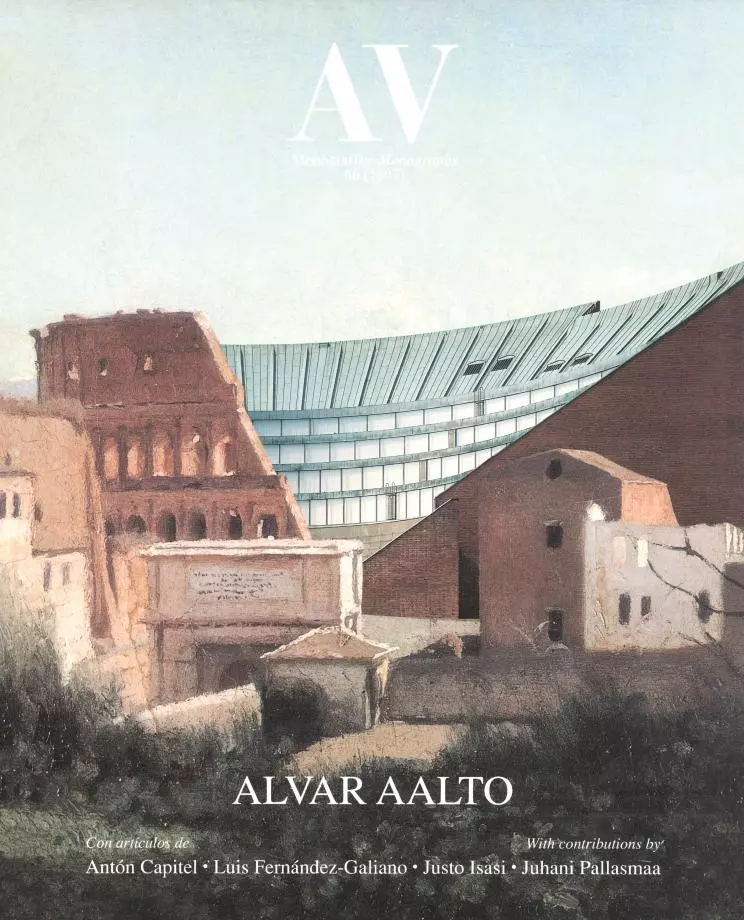

It is easy to see which of Aalto’s projects could arouse more contemporary emotions: the scenographic warpings of the New York pavilion, the urban severity of Rautatalo, the ceramic and programmatic collage of Muuratsalo, the rigorous topography of the Maison Carré, or the undulating bands of Pavia. Neither is it hard to reckon that the popularity of his characteristic forms will last beyond the centenary: the fans and sheaved bundles, the onomastic waves and lake-like perimeter of his emblematic vase. But we cannot prognosticate which of the many overlapping and superposed Aaltos will emerge preferentially in the violent limelight of commemoration: the tactile architect of birchwood furniture pieces, the romantic Scandinavian in love with a rough Mediterranean, the champion of the small man and grand nature, or the oneiric draftsman of soft pencils and stubborn ideas.

Here we present a canonical Aalto which excludes the initial bars of premodern classicism and orchestrates his career in three movements, stitched together by his houses and studios: that which leads from ‘Turun Sanomat’ to Villa Mairea, a doctrinal and linguistic evolution that has its climax in the brilliant episode of the Viipuri library's cliffs and suns; the uncertain period of war and its aftermath which embraces the American temptation and the Finnish decision, with the happy maturity of Saynatsalo and Otaniemi, during the painful years of transit from Aino to Elissa; and a mannerist polyphonic finale, which combines the democratic urbanity of the civic centers with the white and theatrical monumentality of the architect who dreams of Venice in Helsinki. Three movements which describe - but do not explain - the enigmatic continuity of sentiment and the blurry limits of modern reason.