We begin to celebrate the centenaries of those who were our masters, and the many anniversaries in 2013 prompts a pixelated portrait of architecture after the First World War with ten biographies of figures born on the eve of the Second. In my case, which is that of many other architects schooled in Madrid in the late 1960s, surely the most influential was Alejandro de la Sota, professor at the ETSAM at the time, while we admired the residential Coderch from a distance, overlooked Aburto in Cabrero’s shadow, reduced Bonet to the period of his exile, and understood the great Fisac of concrete bones more than the one of flexible formwork. During our university years, Tange was already history, we imitated the Candilis of Algeria or Berlin, and in urbanism we studied the Ekistics of Doxiadis, while Amancio Williams and Mario Roberto Álvarez would be late discoveries, despite our cultural dependence on Buenos Aires, then capital of Spanish-language architectural publishing.

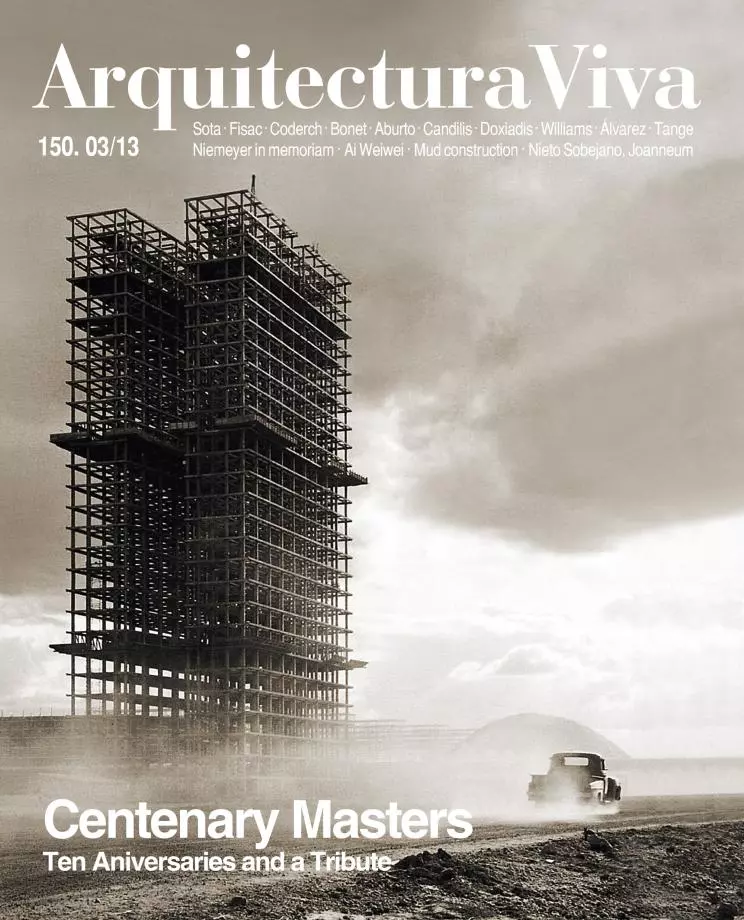

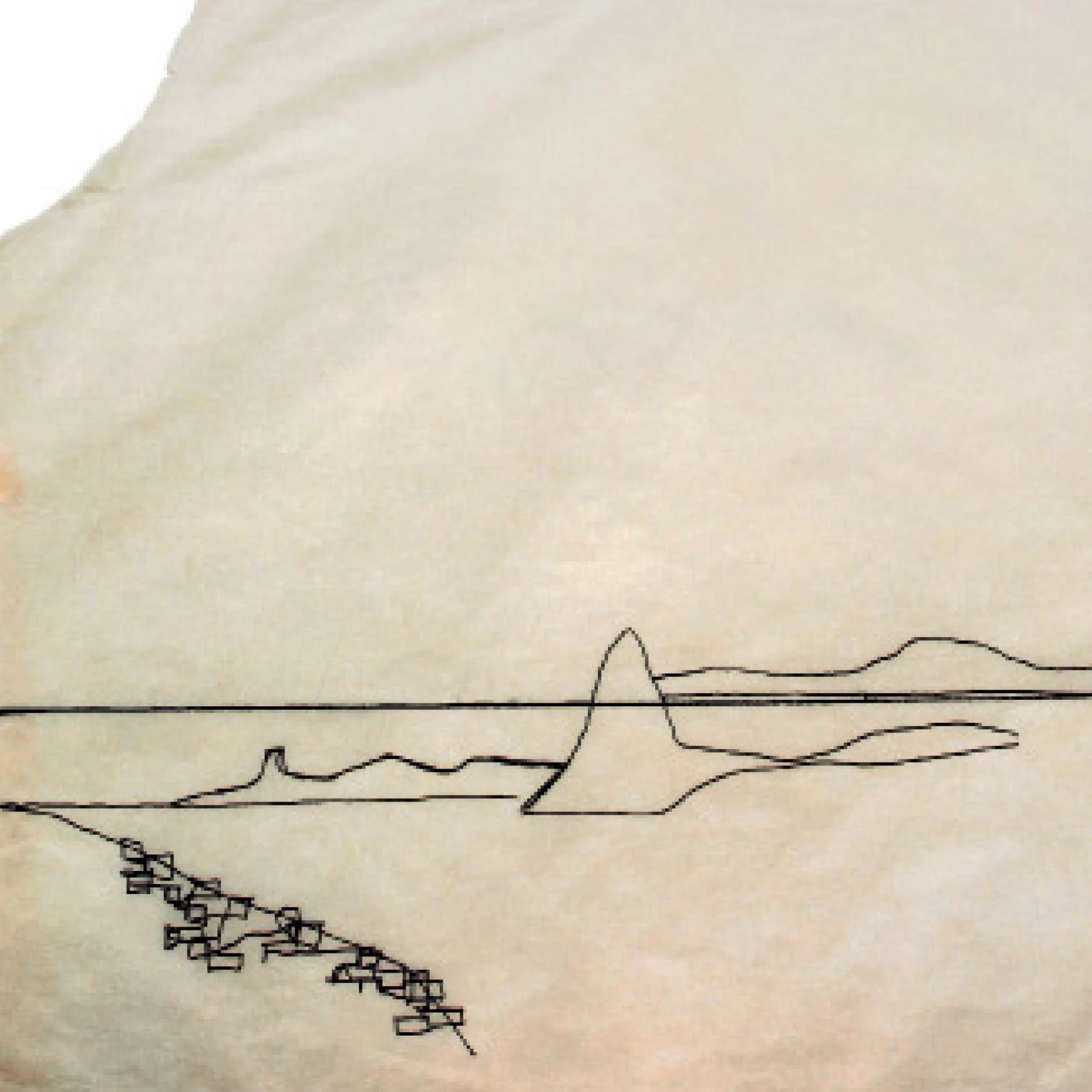

This mesh of trajectories begun in 1913 paints a landscape of modern fidelities, because all elude the ideological and formal fractures that would lead to postmodernity. Next year will mark the centenary of the outbreak of what was then called the Great War, which devastated the material and intellectual foundations of the Ancien Régime, and the Venice Biennale to be curated by Rem Koolhaas proposes a historical analysis of the process by which the modernity born of those convulsions was absorbed in different countries, blurring their specific profiles and giving rise to an international architecture that globalization has spread around the planet. Few figures represent this century of transition as well as Oscar Niemeyer, whose death at 104 ended a journey that took him from an unmistakably Brazilian tropical modernity to a formal repertoire capable of multiplying itself, in his own country and the world, as an architectural trademark attached to his larger-than-life personality.

We thus have to complement the ten centenaries with a tribute to the great master who went past that mythical age of 100, and for this task, who better than Roberto Segre, for twenty-five years our chief historian and critic for all Latin American, let alone Brazilian, themes. Fatality has interrupted his life at a time when he was in full possession of his creative and intellectual capacities, and this issue which opens with his own obituary of Niemeyer closes with another on himself, completing a perfect and painful circle. Fifteen years ago he had the generosity of celebrating the tenth anniversary of Arquitectura Viva with a long article where he compared our trajectory with that of the canonical Casabella-continuità of Ernest N. Rogers, to now leave us barely a week after sending us a no less lengthy review of our Atlas series, which he exaggeratedly pronounced a great publishing event. With Roberto’s sudden and premature disappearance we have lost an exigent master and an excessive friend.