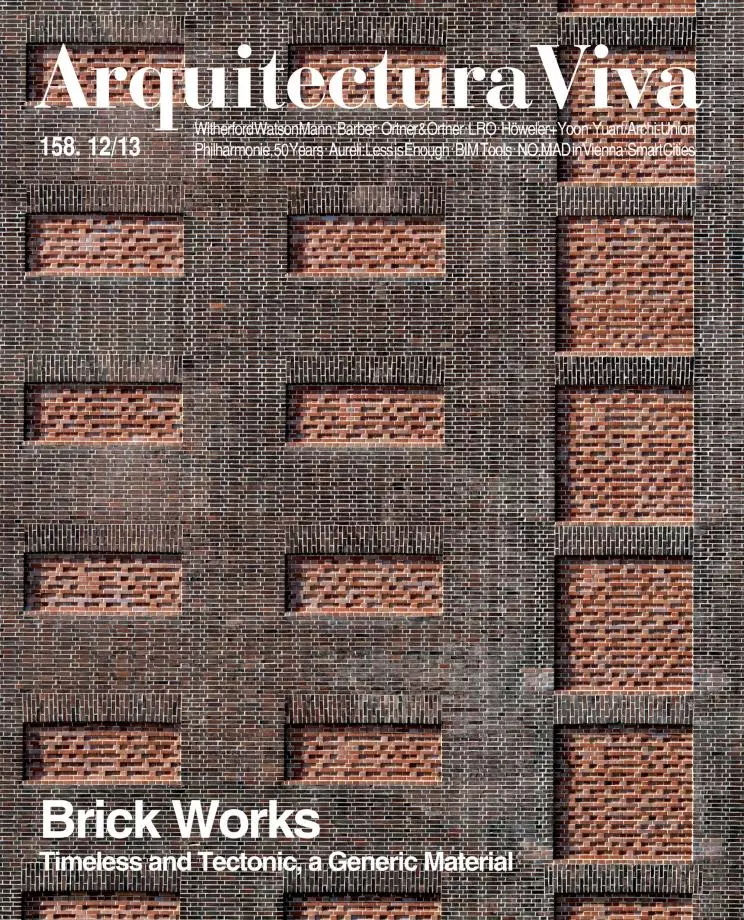

Brick is the Esperanto of construction. While a few cultures may ignore its grammar, those that command its vocabulary are legion, expressing physical needs and immaterial yearnings through the essential language of ceramic prisms. Versatile as no other, and infinitely varied both in the clay or baking of its pieces and in the elaborate syntax of its bonding, brick is a material that unites accessible techniques and production processes with easy laying on site, and excellent thermal and mechanical behavior with the organic elegance of its aging through the abrasion of touch or the aggressions of weather. Anthropological in its dimensional reference to the human hand and alchemical in its transformation of mud into exact geometrical prisms, brick is a clay that has received a warm breath to become the universal language of construction, archaic in its roots and sophisticated in its contemporary uses.

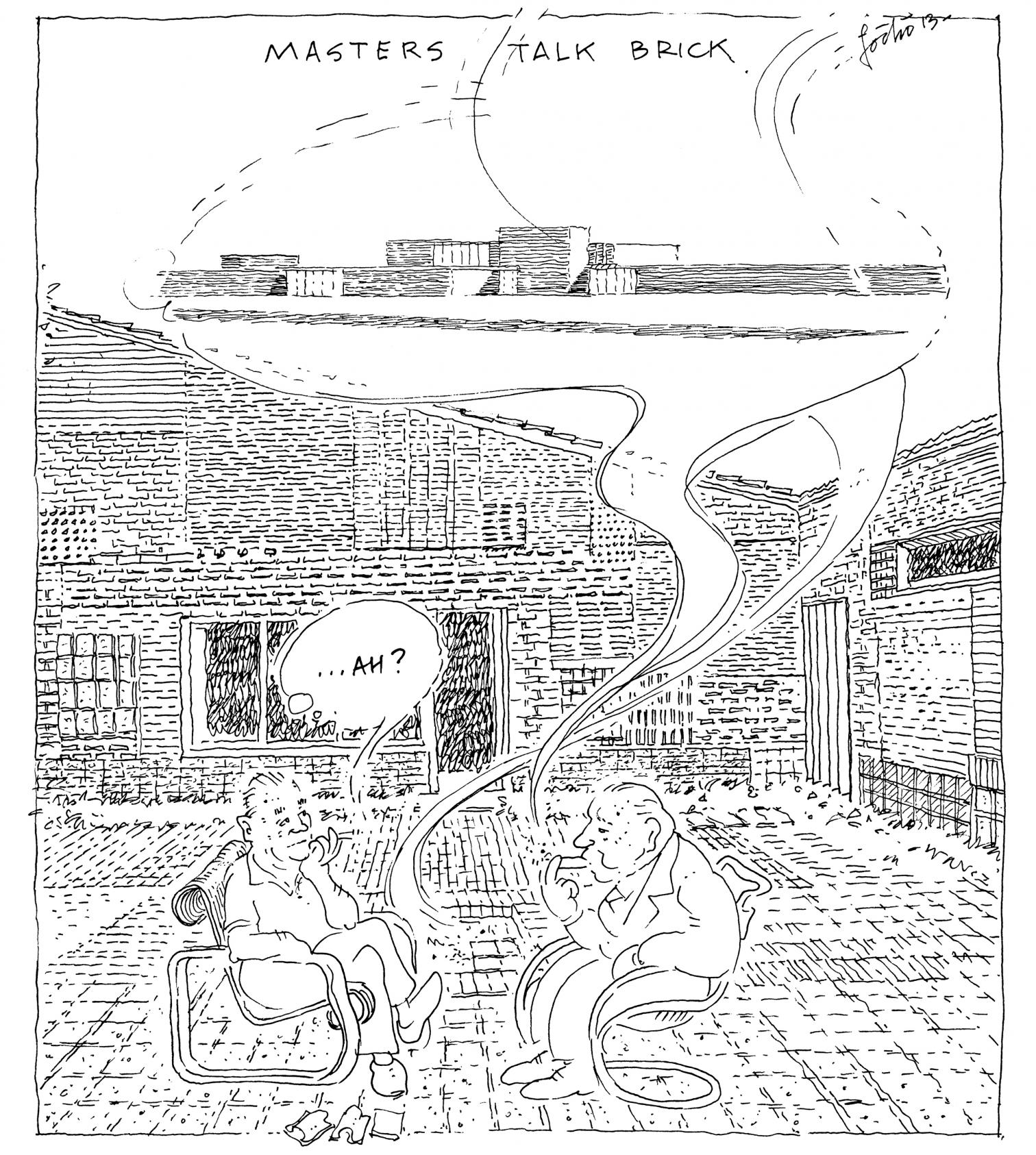

Though some of the most dogmatic figures of modernity condemned it to the darkness of immobile tradition, masters like Mies van der Rohe turned it into the measure of all things, and the meticulous modulations of his courtyard-houses taught a generation of architects; and other masters like Alvar Aalto joined the lyrical ceramic experiments of his summer house in Muuratsalo with the handwritten thank you letters to the six workers that built the brick walls of Säynätsalo Town Hall, because the bond needs the careful dedication of those who assemble it. Brick is modern and timeless, and lends itself both to the rational claim of geometric order, modular grids and productive standardization, and to the phenomenological defense of tactile perception, warm appearance, and solid permanence: precise and common, the friendly rigor of ceramic language is immediately understood in any geography or climate.

In Spain, brick has been traditional and modern. The so-called “poor material of beautiful Mudejar monuments” was traditional in its historical and vernacular use, and modern in the functional sobriety of its serial, humble pieces. The Spanish Silver Age found home in the exact brick prisms of the Residencia de Estudiantes, where Antonio Flórez expressed the spirit of renewal of Giner de los Ríos and Cossío with monastic laconicism, and the Casa de las Flores, where Secundino Zuazo materialized with bare ceramic volumes a new way of inhabiting the city; meanwhile, the avant-garde fascist Ernesto Giménez Caballero linked brick with ordinary people, claiming that it should be enclosed in classical stone frames and crowned with Gothic slate roofs. But brick has reached our days free from restrictions and material mixtures, bold in its modest and self-sufficient composure, the genuine shared language of elemental construction in the planet.