The symbol of the north was enamored of the south. Alvar Aalto, the greatest of Scandinavian architects, longed for the Mediterranean all his life. “I always have a trip to Italy in mind,” he often said. When he embarked on his final voyage, his widow buried him under an Ionic capital of Italian marble: a paradoxical homage for a modern artist, more so for someone who on publishing his complete oeuvre had eliminated the classicist buildings of his youth, yet a fitting tribute to a passionate temperament who in Helsinki dreamed of Venice.

To be sure, the south of his fantasies and travels was not entirely a classical south. Visiting Spain in 1951, he shocked his Madrid colleagues with his lack of interest in the Prado Museum, or with his ostentatious way of turning his back on El Escorial: only vernacular constructions seemed to merit his attention. What Aalto was looking for in the south was popular ingenuity in the use of materials and the anonymous wisdom of hill towns: the refined design of everyday objects and the exact beauty of landscapes built by necessity, time and chance. Between design and landscape, his own architectural work unfolded for half a century.

Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto was born on February 3, 1898 in the village of Kuortane, and spent his childhood between the drawing board of his topographer father’s home office and the lacustrine sceneries of central Finland. One inevitably relates the undulating forms of his future architecture to the contour lines and capricious shapes of his native region’s numerous lakes, and that aalto is the Finnish word for wave only serves to corroborate the poetic probability of a destiny foretold.

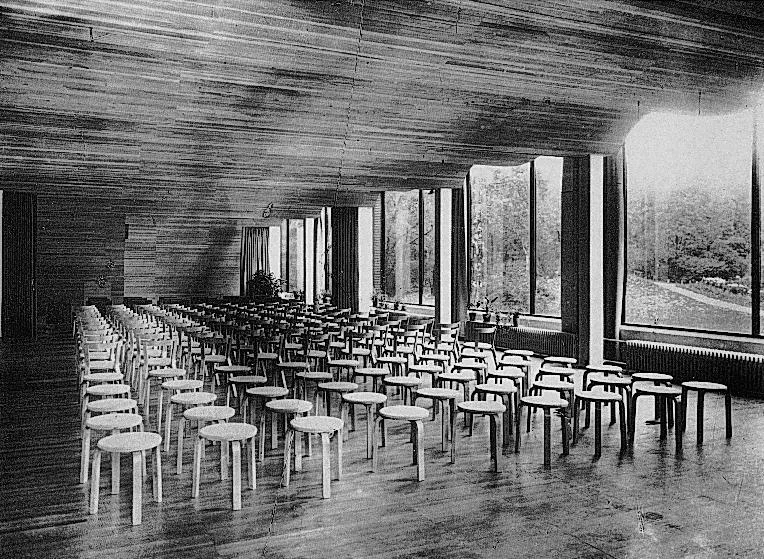

The distancing from the Modern orthodoxy with the use of natural materials and curved lines began in the Viipuri library (1933-1935) and culminated in the Finnish Pavilion in New York (1939).

Educated at the Classical Lyceum of Jyväskylä, a small town that takes pride in being known as Finland’s Athens, Aalto returned there in 1921 on completing his higher studies in Helsinki to set up an architectural practice, willing to turn it into the Florence of the north, as he wrote with proselytizing zeal in the local press. Such Tuscan fervor, shared with a large group of Scandinavians led by the Swede Erik Gunnar Asplund who together formed whatwas called Nordic classicism, left a serene and solemnmark on his early buildings. In 1924 hemarried Aino Marsio, an architect two years his senior who was working at his studio and who would be his closest collaborator until her death in 1949, and the young honeymooning couple did a pilgrimage through their own particular Italian holy land.

A competition won in 1927 prompted him to transfer the studio to Turku, and his arrival in this cosmopolitan city, which had been Finland’s capital before the Russian tsars chose Helsinki, coincided with the spread there, through apostles like the Swede Markelius and the German Gropius, of the modern gospel. Together with his compatriot Erik Bryggman, Aalto was converted to the creed of the International Style, and three functionalist works soon put this peripheral architect at the heart of the newmovement: the headquarters of the newspaper Turun Sanomat, the tuberculosis sanatorium of Paimio and the library of Viipuri.

In 1933 he relocated to Helsinki, where he was to live the rest of his life. By then the young Aalto was already recognized abroad as a modern figure, but the next few years saw the Finnish architect straying away from the white, mechanistic and rectilinear orthodoxy of the international canon in favor of the natural materials, vernacular details and curved lines that had already appeared in the laminated timber furniture of the sanatorium or the undulating acoustic ceilings of the library.

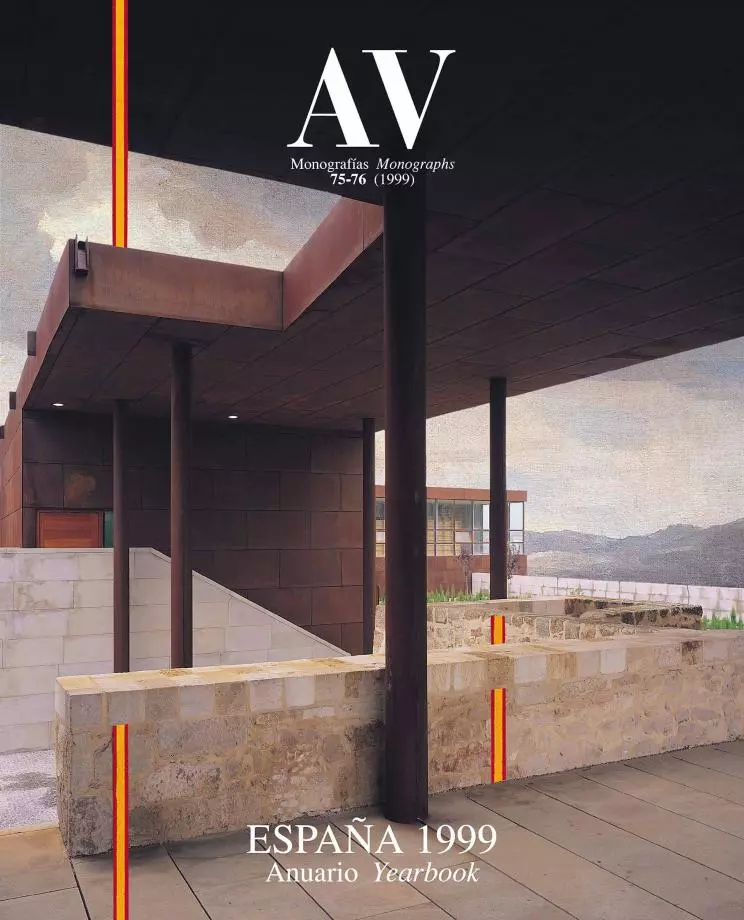

Aalto’s work offers a varied repertoire of ceramic materials. Right, the summer house that the architect built for himself in Muuratsalo (1952-1953), the Säynätsalo Town Hall (1949-1952).

This heretical organic modernity soon crystallized in two masterworks: the Villa Mairea, a vacation home for his friends and patrons the industralists Marie Ahlström and Harry Gullichsen, whose lyrical collage of references to the Finnish forest, Japanese tradition and avant-garde language made it an immediate myth; and the Finnish Pavilion at the 1939World Fair of New York,whose floating undulating wooden walls instantly captured the imagination of visitors and gave its author the status of a master internationally admired for his formal eloquence, sensitivity to nature and tenaciously formulated humanistic convictions.

The outbreak of World War II interrupted Aalto’s career but numerous connections in Europe and the United States (he was a friend of Le Corbusier, Léger, Wright, Hemingway, the Rockefellers...) exempted him from combat service, which took the lives of six architects of his studio, in exchange for the propaganda work of giving lectures around the world to solicit aid for his country. Through these tours the architect spread word on Finland’s plight, but they also served as a vehicle by which to promote his artistic and social ideas, enabling him to boost the growth of a commercial network for the furniture manufacturer Artek, a company he had founded to exploit his popular designs in laminated timber, and obtaining for him the assignment as full-fledged professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a job he was to perform intermittently and which would result in a major commission: a student residence at MIT, which Aalto carried out during the early postwar years, using rough-textured bricks to raise his characteristic sinuous forms on the banks of the Charles River.

The fan-shaped plan of the Otaniemi auditorium (1953-1967) and the marble of the Finlandia Hall (1962-1975) characterize the rhetorical monumentality of Aalto’s last period.

Aino’s death in 1949 was a big trauma for Alvar Aalto. As wife and collaborator she had been his strongest emotional and professional support for a quarter of a century, taking charge of interior design, Artek or exhibitions, but above all playing the role of a confidante and accomplice without whose approval Aalto felt insecure, perhaps because, as his biographer Göran Schildt suggests, in Aino he found the mother he had lost as a child. Though extroverted, fond of traveling and a womanizer, Aalto remained attached to her by an umbilical cord of dependence. News of the gravity of her illness had him rushing backing to Finland from the United States, in time to stretch a last present over her bed: the mink coat she had dreamed of as a symbol of the success they had attained together.

Aalto’s life went adrift in the following years and only began to alight from an erratic alcoholic crisis with his second marriage. In 1952 he married Elsa Kaisa Mäkiniemi, renaming her Elissa. Simple, spontaneous and twenty-three years younger, this new wife initiated a period of vitalistic happiness for Aalto, bolstered by growing professional recognition in his own country. If he had for a while considered the possibility of settling in the United States, victory in two important Finnish competitions – for the National Pensions Institute and the Otaniemi campus of the Technical University, both in the Helsinki area – made him decide against it once and for all, and for a long time these two large public commissions were the center of his attention. These expanded upon the unique synthesis of Mediterranean classicismandNordic tradition that he had already tested in two small masterpieces in brick and wood: the town hall of Säynätsalo and, not far fromthis locality of central Finland, his own summer house at Muuratsalo.

On completing the town hall Aalto had written a personal note of gratitude to each of the six men who had carried out the brickwork; in the vacation house he had produced a motley sampling of bricks and bonds that was a tribute to warm ceramic textures, as against the abstract coldness of conventional modernity; and he used the same pleasant brick masonry in profusion for the two major works of those years. At Otaniemi, however, dominated by a huge fan-shaped auditorium evoking classical theaters, Aalto chose to clad the architecture school with Carrara marble, in tribute to his own discipline and initiating a monumental and rhetorical phase of his career that was to be the last.

The formal mastery and luminous sensibility of this mature Aalto are present in the polyphonic scenography of the Imatra church, in the organic sensual curves of the libraries and in the wise random landscapes of the Seinäjoki and Rovaniemi civic centers, but especially in the large-scale Helsinki buildings such as the Enzo-Gutzeit headquarters or the Academic Bookshop, all faced with his beloved Italian marble, and culminating in his great architectural legacy, the Finlandia Hall, a huge auditoriumand convention centerwhose powerful lyrical volume rose on the edge of Töölö Bay and was finished shortly before Aalto’s death on May 11, 1976. The Carrara marble ultimately proved ill-suited to the Nordic climate, with the sheets of stone flaking off and eventuallymaking the building look coated with scales or bark. Technical mishap and poetic justice thus transmuted the monumental solemnity of classical marble into romantic, Scandinavian naturalism.What better metaphor for the fecund failure of an architect who endeavored to reconcile south and north, andwho is buried in Helsinki under a capital of Italian marble.