We commemorate 1914 at the heart of the conflict. A century after the Great War began, we Europeans watch the economic colossus of the continent with precaution, and hope the material giant also becomes a spiritual one. That tragic carnage, started by sleepwalking elites – “blind to the reality of the horror they were about to bring into the world,” in the words of Christopher Clark –, would come to a deceptive closure in 1918 but reopened in the thirties, with the prelude of the Spanish Civil War and the unleashing of the global conflict in 1939. The year before, in the second anniversary of the war’s outbreak in Spain, president Manuel Azaña called for ‘peace, pity and pardon’ in a memorable speech at Barcelona’s City Hall, calling to reconciliation and invoking the ‘muse of chastisement’ so that the lessons of the dead would be heard in the future, but his words were swept away by the winds of history.

As we suffer in Europe and in Spain a turbulence where many see echoes of the blind eves of previous tempests, all eyes look towards a hesitant Germany, unable perhaps to prevent the fracture between north and south of the continent, or the fragmentation of Europe in a mosaic of small regional precincts that threaten its cohesion, but undecided also about its national interest in the long term or its historic role today. In his farewell discourse before the European Parliament in 1995 in Strasbourg, French president François Mitterrand – who was born during World War I and took part in World War II – wanted to leave a bold assertion as a political testament, “le nationalisme, c’est la guerre!,” remembering that “war is not only the past, but can also be our future,” a prescient warning that Angela Merkel repeated at the Paris Elysium in 2013, unfortunately with as scarce consequences as Azaña’s earlier call to the muse of chastisement.

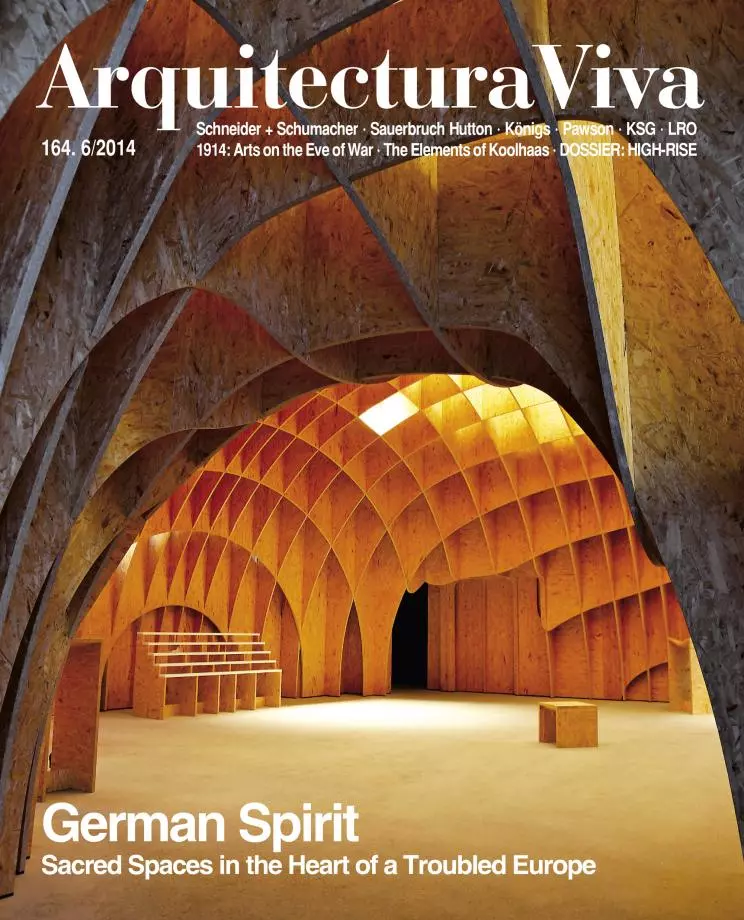

At this European crossroads, after a continental election that has shown the rise of nationalism and xenophobia, and in a geopolitical situation marked by the withdrawal of the US towards the Pacific, the military and energy assertiveness of Russia and the instability of the Islamic world, it is inevitable to hope that Germany will rise to the challenge that comes our way, adding to its economic leadership a political, intellectual and moral one. The different sacred spaces presented here – beyond demographic or sociological reasons – want to be built illustrations of what we expect from the German spirit, architectural metaphors of the high-mindedness which must be shown by the country running Europe today, and expiatory temples of too cruel a memory. Paul Celan wrote that “Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland,” but the German spirit can exorcize that line and become the continent’s instrument to preserve peace and prosperity for all.