Republican? Catalan? Architect? The centenary of Eduardo Torroja will blow oxygen on sterile, worn-out interrogatives. Since the giant stature of one of the century’s great engineers hardly needs revision, the small change of loose arguments in the commemoration will jingle in the pockets of those who try to sequester the saint for private devotion. We can only hope that such pious fervor does not reach the extremes of Velázquez, whose centennial Madrid celebrates through a ceremony of panic theater that disembowels the city in search of a mummy: a true vanitas that links Solana to Valdés Leal. In the case of the engineer, the cult of relics has not yet invaded the funerary terrain, but one can easily imagine that the spoils of his legacy will be fiercely disputed by many.

More original than Sert and more modern than Zuazo, Torroja was the leading figure of construc-tion in the republican period. From the viaducts of the university campus to the canopies of the Instituto-Escuela and from the structures of the Hospital Clínico to those of the new ministries complex, the young engineer was at the core of its most innovative and emblematic experiments, and his two masterworks, the Recoletos pelota court and the Zarzuela racetrack, were both built in republican Madrid of 1935. Franco’s victory brought on at-tempts to erase the architectural mark of such ra-tionalism, and so it was, for example, that José María Albareda’s new Scientific Research Council commissioned Miguel Fisac to erect the Church of the Holy Spirit on the site of the auditorium of the Residencia de Estudiantes, the happy hub of republican intellectual elites and a work of the same architects (Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez) who had assisted Torroja in the Instituto-Escuela and the hippodrome. This perhaps explains the British William Curtis’ erroneous assumption – in his widely diffused history of contemporary architecture – that Torroja then left Spain to carry out the rest of his career... in Mexico! But this active member of Acción Católica who in the Civil War lost no time in deserting to the ‘national’ side, and whom the fascist regime showered with the highest distinctions, culminating with the title of marquis, hardly deserves to be described as republican.

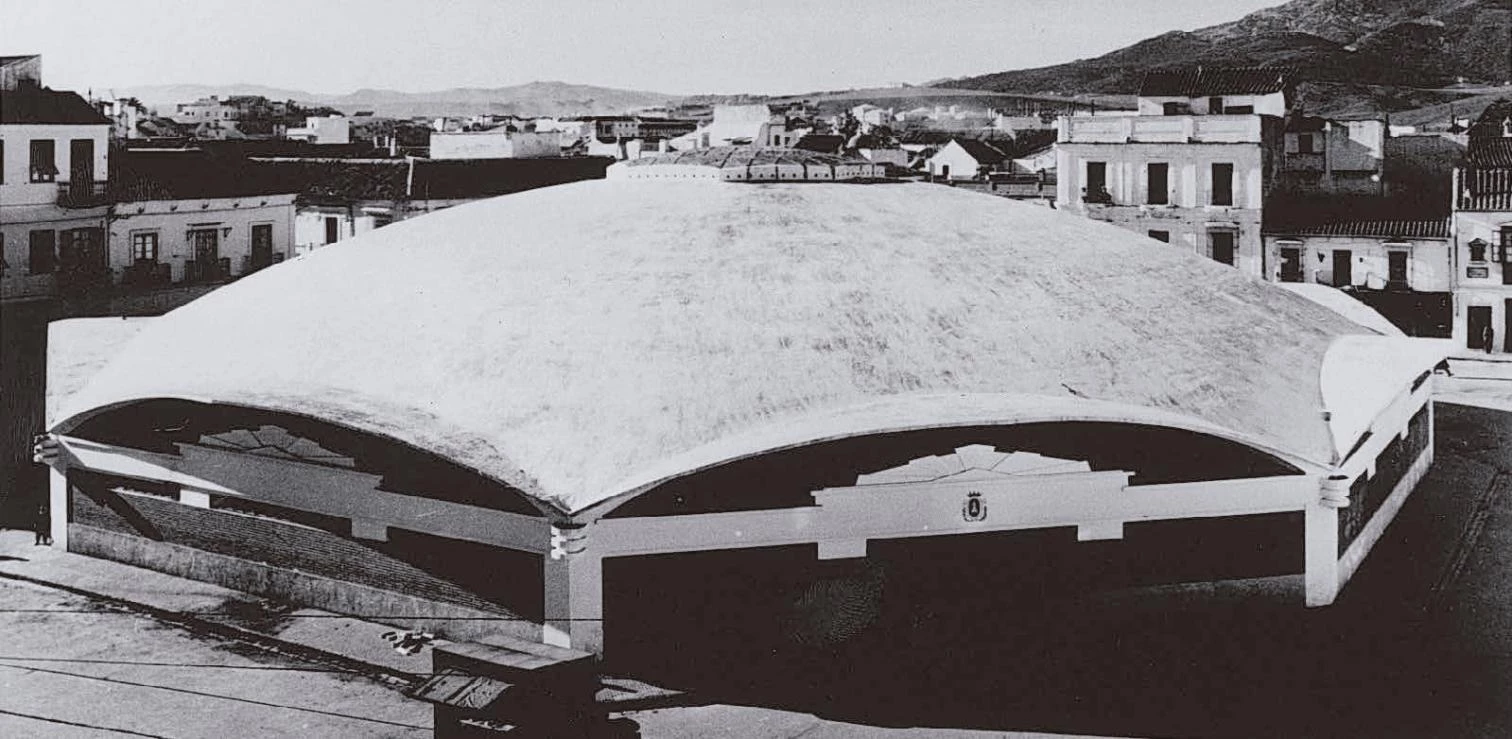

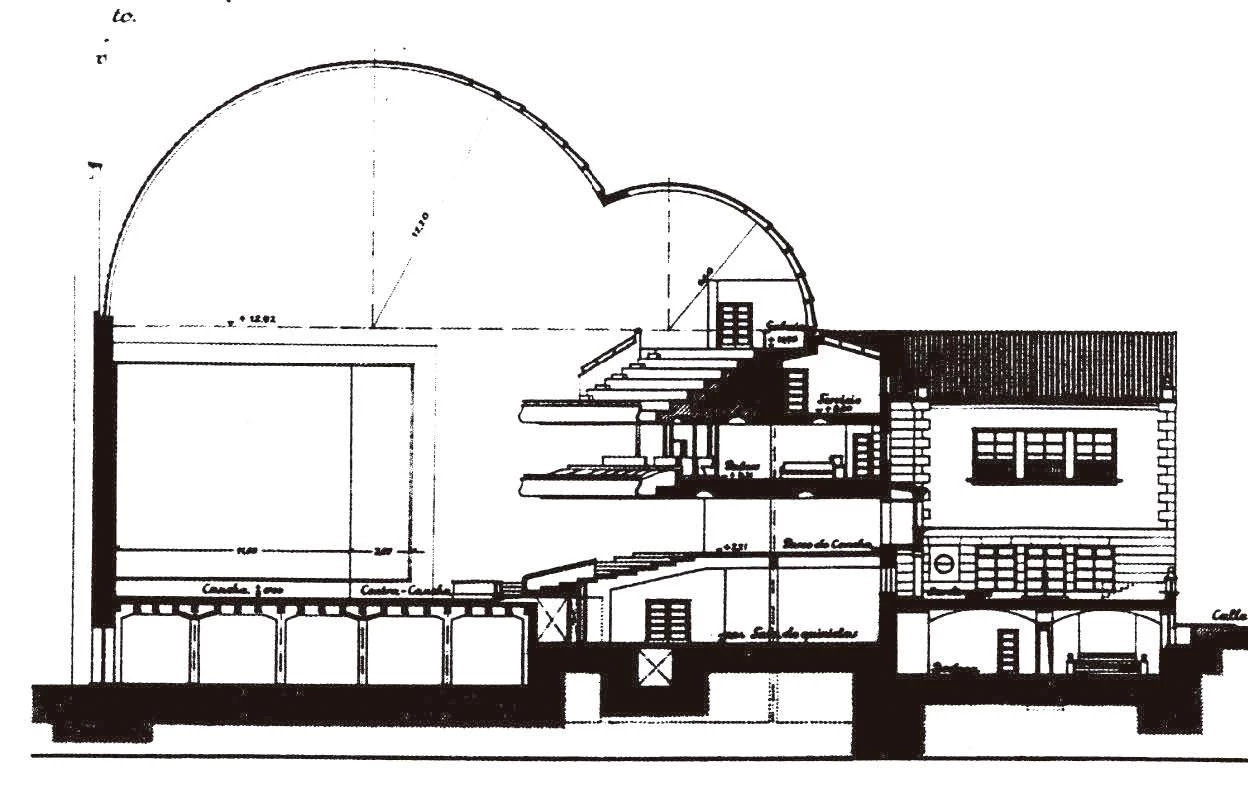

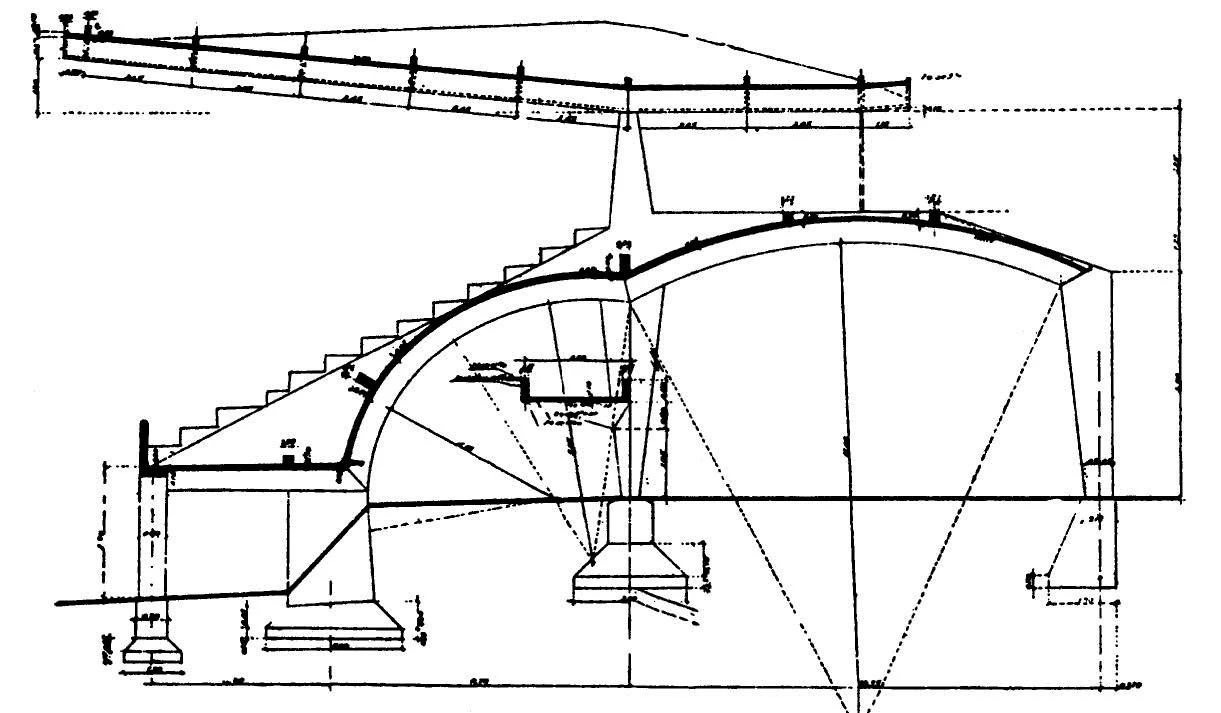

A dome in the shape of a spherical cap in the Algeciras market and a laminated, cylindrical structure in the Recoletos pelota court leave large open spaces free of supports.

Son of an architect and mathematician with far roots in Tarragona, Torroja has also been attrib-uted with Catalan filiations that would relate him to the constructive genius of Gaudí and make his concrete shells descendants of Catalonia’s ceramic vault, linking him in passing to the Valencian Guastavino, who disseminated those fire-resistant structures in the United States. Salvador Tarragó presented him in this context twenty years ago, on the occasion of a commemorative exhibition held at the Association of Civil Engineers in Madrid: if not a Leftist, then at least a Catalan! And Oriol Bohigas has brought such appropriation to extravagant extremes by referring to the engineer as “Eduard Torroja... a Catalan based in Madrid” in the 1998 edition of Spanish Architecture in the Second Republic, originally published in 1970. Surely this new identity allows one to be more benevolent in judging the builder’s postwar works, some of which, such as the church of Pont de Suert, cease to be “ridiculous monsters” and become merely “inexplicable black spots” in modern Spanish architecture. The fact is that he was born in Madrid and died in Madrid, just as it was here that he studied and taught, carried out his professional career, and built the best of his oeuvre. Yet it would be petty to claim him as a Madrilenian, because Torroja belonged more to the larger continent of engineering, and within this, to a nation he alternately called ‘the form’ and ‘the idea’, the marrow of which was a brilliant intuition for geometry.

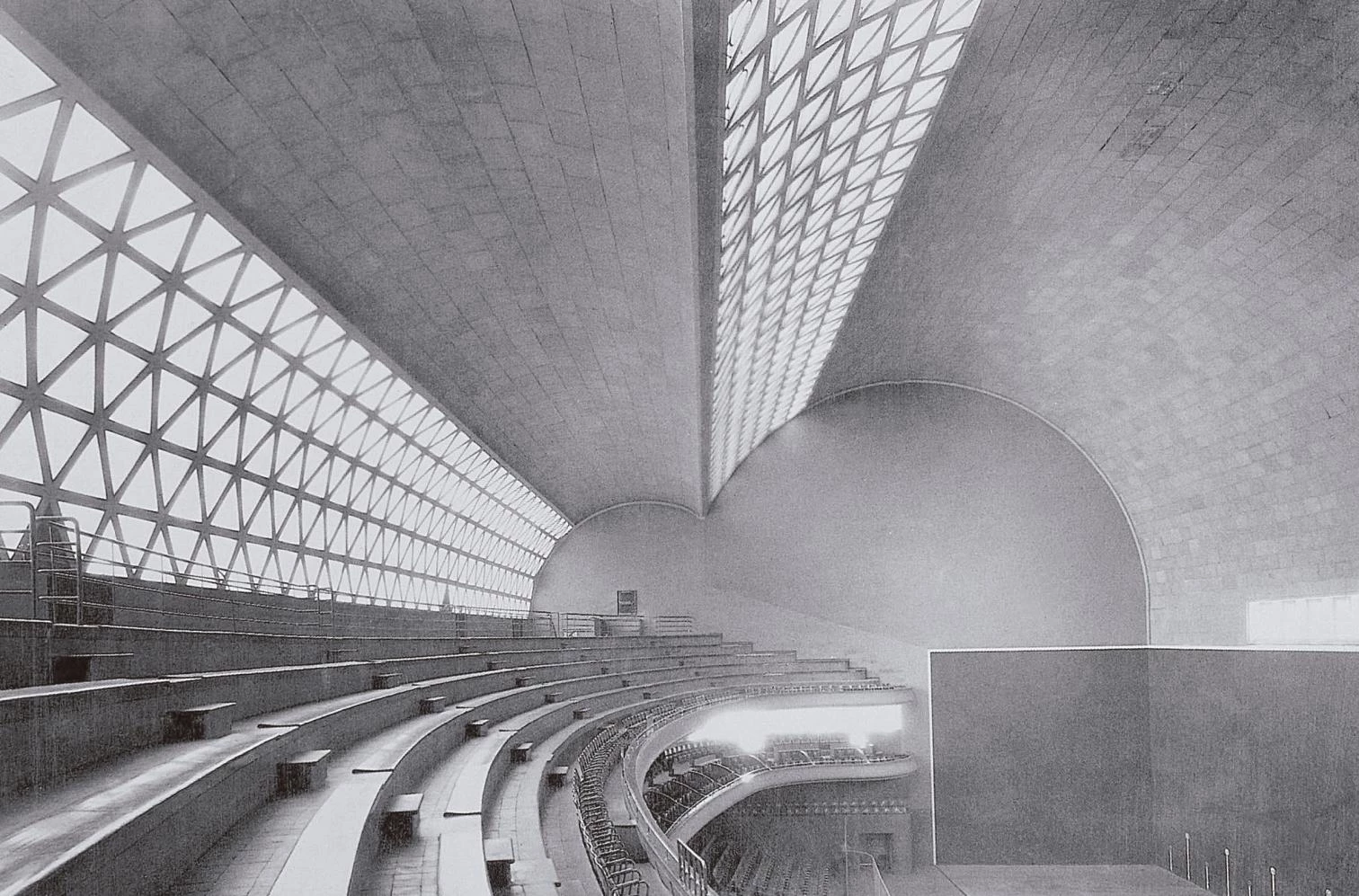

With its cantilevered canopies of repeated hyperboloids, which on edge are only 5 cm thick, the stand of the Zarzuela horse racetrack (above and below) was built in 1935 together with architects Arniches and Domínguez.

Not a republican and not a Catalan, neither was Torroja an architect in the strict sense understood by many members of the guild, for whom naming an engineer an ‘honorary architect’ is to distinguish, through conspiratorial cooptation, the technician who has successfully risen above quantitative depths and reached the Olympian heights of art. Advocating ‘art without artifice’, Torroja transformed architecture without ceasing to be first and foremost an engineer of the enlightened scientific tradition. His extraordinary formal imagination, which led Freyssinet to call him “the master of original constructions”, comes from geometric discipline, structural intuition, and an intimate famiiarity with the material. No writing of his is as instructive and as beautiful as the fragment of Laminar Forms that painstakingly narrates the rational gestation of the racetrack’s emotive geometries, and which gives the relentless beauty of truth to the light, serene rhythm of those impossible canopies. From this line of logic also come the concrete hyperboloids of the Madrid architect exiled in Mexico, Félix Candela, or the ceramic shells of the Uruguayan engineer of Galician origins, Eladio Dieste. The primary nation of these two builders as well, was geometry, as it has been for Miguel Fisac, who forty years ago joined Gio Ponti and Richard Neutra in signing one of the obituaries that lamented the engineer’s disappearance.

We now celebrate Torroja’s centenary, having just helplessly witnessed the demolition in Madrid of the Jorba laboratories (a singular tower on the airport road popularly known as the pagoda), an emblematic work of Fisac, another mathematical poet of reinforced concrete. Rather than bemoaning the cynical paradox, let us make some reflections. Since the Recoletos pelota court was bombed during the siege of Madrid in the war, the Zarzuela grandstand is the most valuable remaining Torroja construction. But thanks to the shady entrepreneur Enrique Sarasola, this racetrack of Madrid has been closed for years, and we all know what happens to buildings that have long fallen into disuse. After all, no other reason was put forward for the razing of Fisac’s Jorba laboratories... Over the scandal of an indefinite closure – which hurts both the horse racing fan and the architecture lover, who may not even visit the site – hovers the danger of legal or clandestine destruction. This may seem implausible, but since in Madrid the implausible is acquiring the habit of becoming true, the cumulus of institutions involved in the Torroja centenary ought to fight for the hippodrome’s reopening, as this would be the most efficient and fertile way of honoring the engineer. Otherwise we will be doomed, as with Fisac’s pagoda, to the grotesque situation of hearing Town Hall propose its reconstruction while demolition is underway.

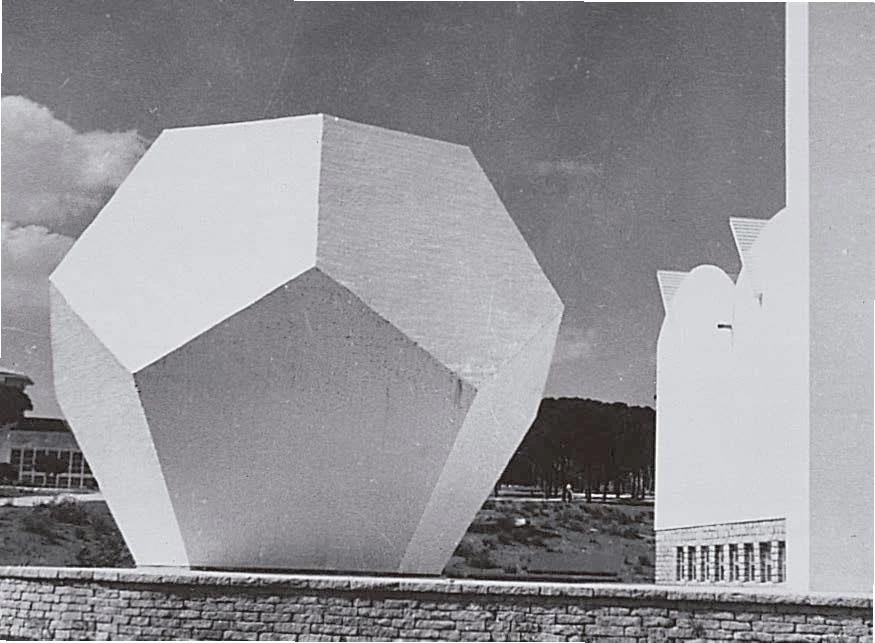

Among his projects developed after the Spanish Civil War are the dodecahedron-shaped coal deposit built in 1951 for the Eduardo Torroja Institute (above) and the Sidi-Bernoussi water tank erected in 1961 (below).

And in this staging of the absurd, we may also fear the reconstruction of the Recoletos court, which should not be short of new locations. Since the sport is Basque pelota, it could well go up near the Guggenheim, thereby compensating for the absence of the Guernica, once claimed for identical figurative reasons. Or, in referenceto the engineer’s alleged Catalan origins, it could rise beside Barcelona’s facsimile of the 1937 pavilion, forming a theme park of modern architecture that competes at once with Port Aventura and the Poble Espanyol. Candela and Dieste already have replicas of their shells in Valencia and Alcalá de Henares, so it would not be prudent to underestimate the contagious nature of simulacra.