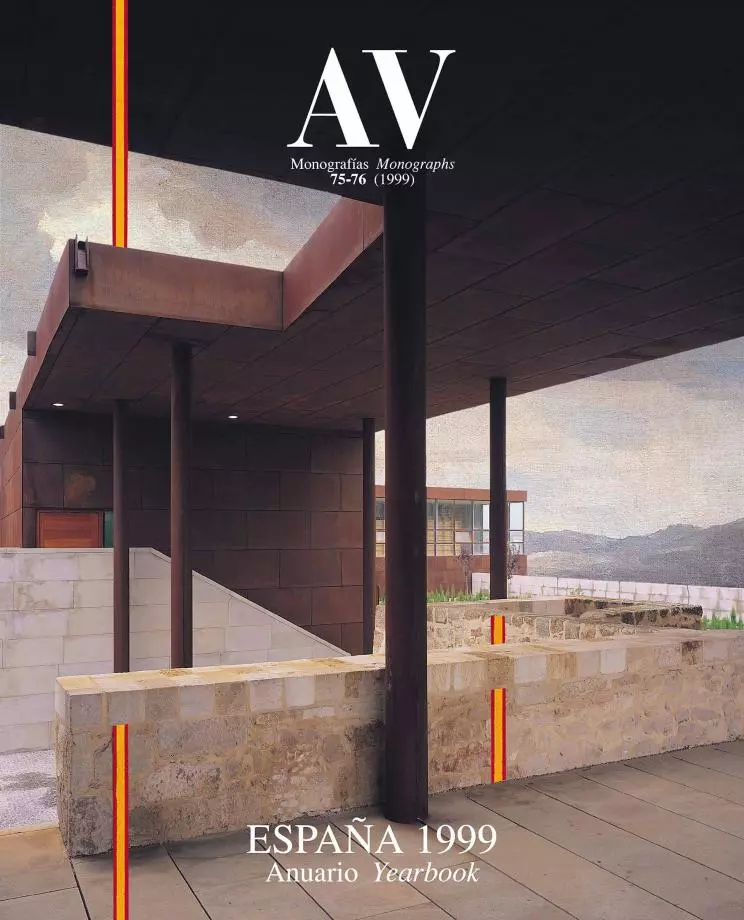

The hermetic, sharp edged geometries of the Kunsthaus that Peter Zumthor has built in the Austrian town of Bregenz supply a powerful metaphor for the interpretative impenetrability of art.

The year 1712, an anonymous writer in London proposed the building of a museum of fashion in the form of a sphinx. Almost three centuries later, museums of art express their equally enigmatic character through hermetic geometries. The use of the sphinx in the London museum would have conveyed the mysterious and unpredictable nature of fashions, which alter habits or raiments in an inexplicable manner. In today’s museums of contemporary art, which are so closely related to fashion, and whose fluctuations are often as arcane as the swayings of the catwalk, the sphinx has given way to geometry. The Egyptian figure is now a thing of theme parks, and the only recently constructed building with a sphinx shape is a big hotel and casino in the strip of Las Vegas, so it is only reasonable for museums to prefer to manifest their magical hermetism through elemental and crystallo graphical solids. Thus the perplexing mutations of taste are enclosed in the self-withdrawn exactitude of a geometrical sphinx.

The ties between art and fashion are irritating to many, for whom art is permanent, masculine and serious, not to be mixed up with something variable, feminine and frivolous like fashion. Nonetheless, any historian knows that they coexist in the realm of taste, representation or consumption. Their current fraternity in the territory of museums can be interpreted as the kidnapping of art by the society of spectacle, but also as the cultural upgrading of fashion and a result of an increased awareness that the two coincide in a secretive and ever changing terrain. Architecture encloses these flitting fictions in buildings of sharp precision, and the rational perfection of museums offers an essential counterpoint to the emotive accident they contain, while providing a material metaphor for their interpretive impenetrability. The hermetic prism accommodates the morbid uproar of fashion and the arts, but also warns us about their incomprehensible character: only the initiated can hope to uncoil the skeins of this mysterious temple.

The fundamentalist rigor of the modern avant-garde extends without sutures in the Kunsthaus, the dry, luminous minimalism of whose interiors exemplify the orthodoxy of contemporary art spaces.

Of course all this seems contradictory to the usual experience of fashion in the museum. The world’s major traditional museums hold monographical shows on clothes designers as a sign of their sensibility to mass culture, and fashion exhibits are as popular as anthologies on impressionists. The Metropolitan, which houses a costume institute, organizes exhibitions on the history of the dress, but attracts multitudes with its presentations of contemporary figures like Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Dior or, more recently, Gianni Versace; the Victoria & Albert has enlarged its clothing collection to cover British fashion of the past half century; and the Louvre, which opened a fashion and textile museum in one of its wings a year ago, has a permanent display of Fortunys and Schiaparellis along with Balenciagas, Chanels, Rabannes or Riccis: haute couture, a spectacle and industry that reflects society and customs, is as present in the great museums as it is in the press or thematic channels. But catwalks are not only seismographs that record tremors of taste: the fashion show has replaced classical statuary in exalting the beauty of the human body, and Naomi Campbell’s sensual hips have taken the place of Doryphorus’s strong thighs.

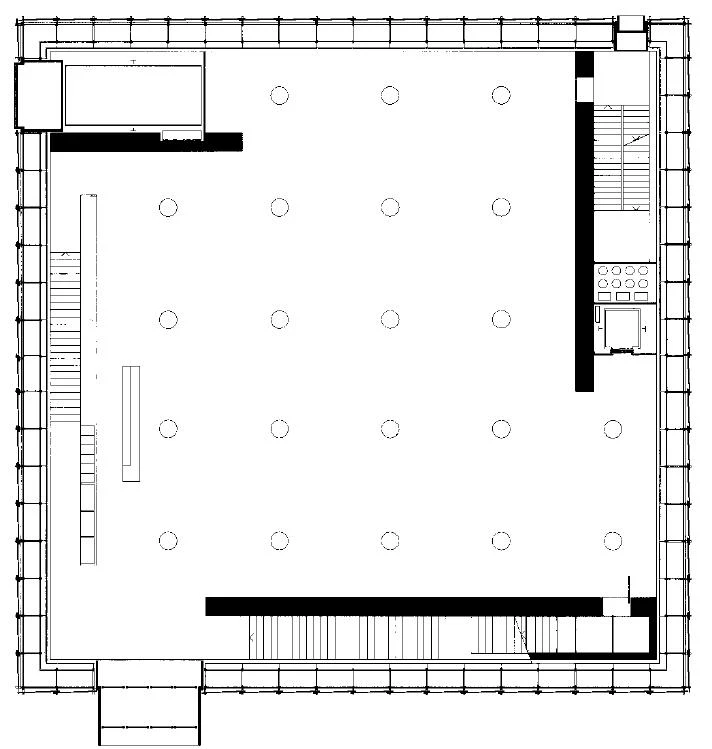

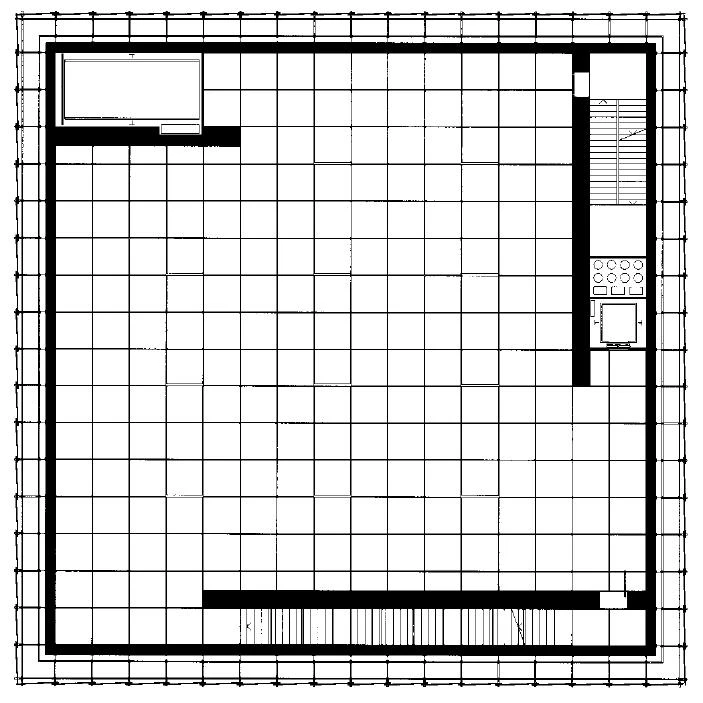

Although the exterior is entirely clad in glass, the galleries are only lit through the glass ceilings, which receive natural light from the large service chambers sandwiched between the exhibition rooms.

The copulation of art with fashion is more ambiguous in matters of patronage. The Guggenheim’s close association with Hugo Boss is quite comprehensible, but not so much Cristina Iglesias’ exhibiting at the New York museum under the auspices of Spain’s Culture Ministry and Carolina Herrera; it is also easy enough to understand the Whitney’s continued collaboration with Donna Karan, but what about with the Italian Miuccia Prada? In contrast, the minimalist rapport between Calvin Klein and the recently demised sculptor Dan Flavin – who decorated the designer’s New York, Tokyo, Seoul and Zürich boutiques with his characteristic neon tubes – is expectable, and joins a modern tradition of crossbreeding that features proletarian uniforms designed by constructivists, surrealist suits by Elsa Schiaparelli, Andy Warhol ads for Vogue, or department store showcases conceived not only by Warhol himself, but also by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein.

In the final analysis, Hugo Boss’s sponsoring an art award with his name or funding the Guggenheim-Soho exhibition on art and fashion that Germano Celant first opened at the Florence Biennale is of little importance; so is the Whitney’s selling T-shirts and caps that juxtapose its logo with Donna Karan’s, or doing a monographic show about Andy Warhol’s long and fruitful relationship with the universe of catwalks. What is important is that art and fashion coexist in a somber zone that tends to block out the light of reason, and that this shared enigma attracts and perturbs us at the same time. Baudelaire encountered modernity in the seduction and constant mutation of women’s wardrobes, but the puritan apostles of architectural modernity, from Loos to Le Corbusier, would only model themselves on the functional and enduring sobriety of men’s wear and the naked body, in that order, finding in the stripping of garments and adornments a persuasive representation of their reductive purism and disdain for decoration. The bare and luminous minimalism that is now the orthodoxy for art spaces is an extension of the fundamentalist rigor of the modern avant-gardes, but paradoxically it also highlights the essential hermetism of creation and the mysterious nature of emotion and taste, which turns these silent prisms into abstract sphinxes.

Opaque Transparency

In the exhibits center illustrating this article, the preference of artists and curators for luminous neutral spaces is brought to an extreme. For the Kunsthaus of Bregenz, an Austrian town on the banks of Lake Constance, Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has made a concrete and glass construction of three superposed galleries forming a translucent prism. While the exterior is entirely clad in glass, the galleries are closed perimetrically by concrete walls, in such a way that they are lit only through glass ceilings, which the facade light reaches in turn through large service chambers sandwiched between rooms. This at once refined and perverse scheme that allows homogeneous toplighting in a multistory building exemplifies the opaque transparency of contemporary art, as well as its protagonists’ liking for the figurative silence of its architectural containers, an inclination which has stirred up conflicts for Richard Meier in Barcelona, Rafael Moneo in Palma de Mallorca and Álvaro Siza in Santiago de Compostela. At Bregenz, however, Zumthor has opted for the anonymity of geometry, transcending the homogeneous neutrality of art spaces with a lyrical and hermetic crystalline cube.