The houses of the masters are at once self-portrait and experiment. From the several residences and offices of Frank Lloyd Wright to the mythical, essential cabanon of Le Corbusier, the gods of the 20th-century have taken a human dimension in the houses designed for their own use; of the holy trinity of modernity, only the laconic Mies van der Rohe eludes scrutiny, blurred between the summary sketches of the house for himself in Berlin, which was finally never built, and the pale photographs of his apartment in Chicago. But the ten gathered here – from the Viennese settled in California following the path of Wright to the Galician who dreamt of Russia in an Iberian finis terrae – show the self-absorbed daring of the draftsman who looks at himself in the mirror, or the curiosity of the doctor who uses his own body to test a vaccine or a remedy.

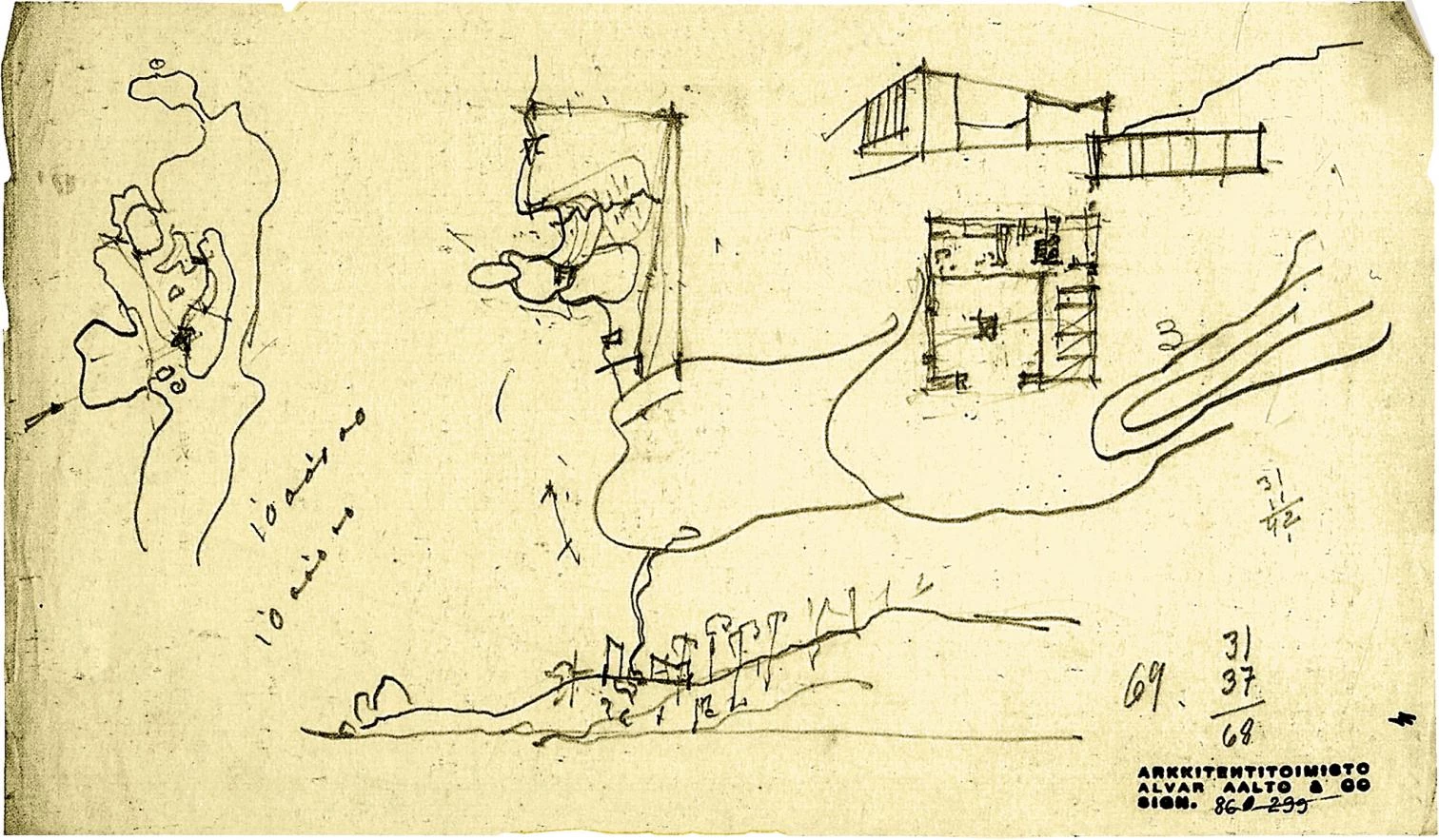

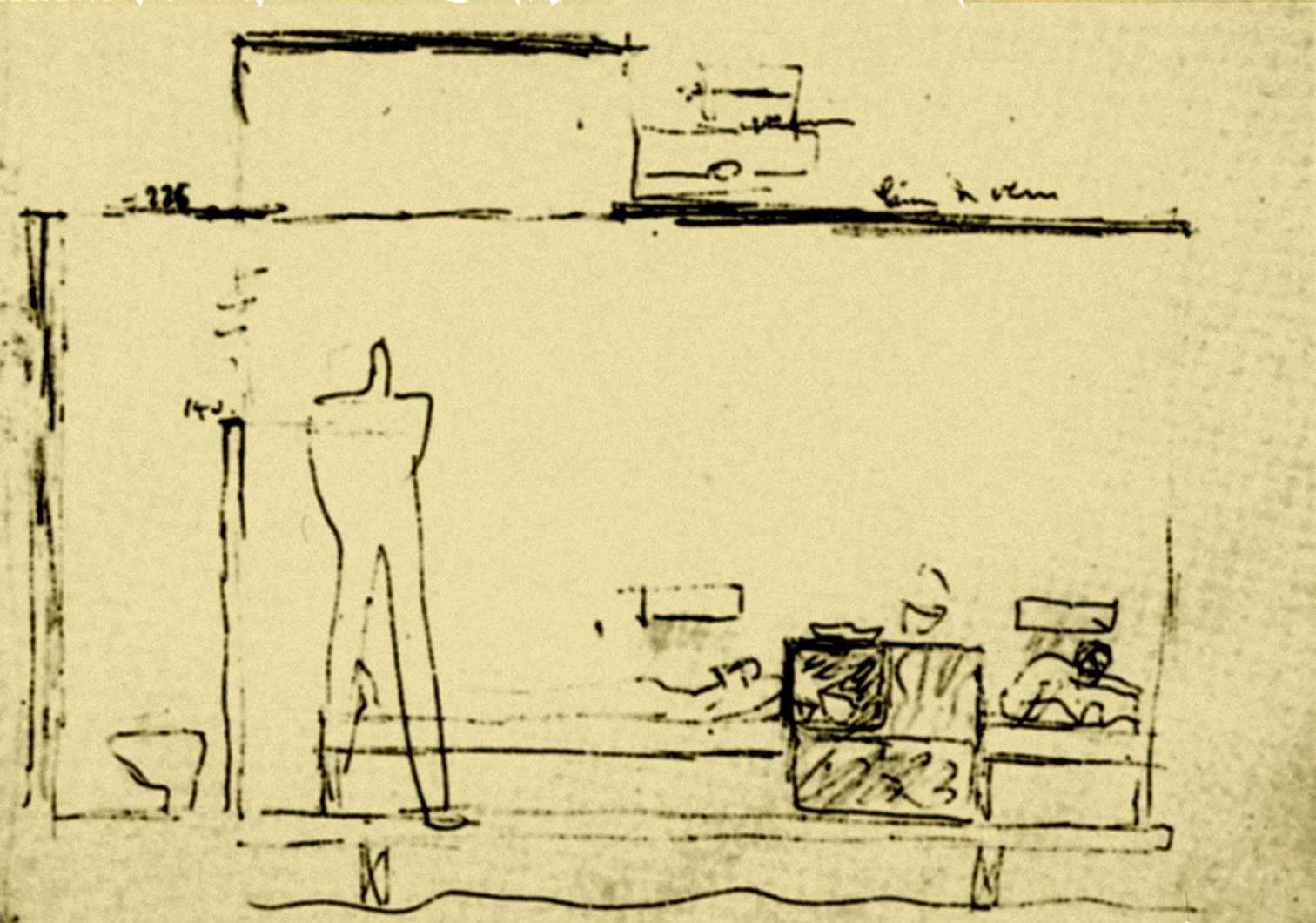

This was the case of the European expatriates that colonized the American West, be it the Rudolf Schindler who created a campground with hammocks, fires and bamboos or the optimistic and elegant Richard Neutra with his refined, geometrical glass houses, while the melancholy Konstantin Melnikov built in Moscow a cylindric, late icon for a jaded revolution; this occurred also in the Scandinavian houses, from the restrained innovation of Gunnar Asplund in his summer shelter to the experimental genius of Alvar Aalto in Muuratsalo, and including the elementary box of the Anglo-Swede Ralph Erskine in his country of adoption; and this happened finally in the essential constructions of the designers that looked for answers in the vocabulary of manufacturing, in autobiographical narrative or in the exact beauty of the shapes defined by engineering logic, from the French Jean Prouvé or the British couple formed by Alison and Peter Smithson to Eladio Dieste, the Uruguayan of Spanish roots whose reinforced brick shells come here right before the lyrical and tectonic inventiveness of the Atlantic house that rounds off the sequence, a tribute from the author of this painstaking research work, José María de Lapuerta, to his master Ramón Vázquez Molezún.

Some extraordinary accomplishments and some failed attempts, some permanent residences and some summer houses, all of them have in common the thrill of contemplating the masters taking on the role of being their own clients, exploring at once the intricacies of their mood and the possibilities of technique. Perhaps narcissistic inasmuch as self-portraits upon the still surface of an intimate lake, and perhaps reckless in their insomniac pursuit of innovation, these ten houses of architects were not built to be shown or to be sold, and for this reason they may shed some light on the most common dilemma of residential construction that, paraphrasing Marx, we could express with a rhetorical statement: in public spectacle, forms without function; in private development, functions without form. Here, functional forms serving both need and experiment.