Cities of ‘92

The events anticipated for 1992 have each had very different consequences for the urban development of the cities of Barcelona, Madrid and Seville.

Ten years from now we will be talking about the Generation of 92. This will have little to do with the celebrations of that summer, and much to do with the hangover that follows. Besides games, festivals and fairs, 1992 is a key year for Europe: the threshold, for the European economy, of a process into which we are rushing with a keenness bordering on the reckless. If this is not checked, the smugness with which we are heading toward that anniversary is bound to result in disappointment, even as the euphoria of the events dies down, and the Generation of ‘92 will enter our historical consciousness with the bitter taste of ash.

With the slogan, ‘sanitize the center, monumentalize the periphery,’ Barcelona began putting extensive urban reforms into effect, even before having been selected definitively as the host city of the 1992 Olympic Games.

Three cities share the spotlight of the jubilee: Barcelona is to be the costly set of the television mega production of the Olympic Games; Madrid will comply with its turn as European culture capital through an extended and emphatic but on the whole predictable autumn festival; and Seville shall be the “incomparable scene” for the rare archaism of an Expo. The debate on the program of festivities is marginating in the three of them the necessary discussion about their place in the European system of cities. And while politicians and architects beat about the bush, the overflowing waters of economic prosperity go on devastating the physical and social fabric of cities trapped between real estate booms and traffic jams.

The growing notion of European space as a market for cities to compete freely in for capital and talent - applying to this larger geographic framework the free-trade theses dominant in the continent’s national economies - foretells an urban panorama of winners and losers. The question of which cities will fall and which will blossom is bound to depend on how the alternatives addressing the urban crisis are perceived, and on the make-up of the considerable investments that are to be made in coming years. Like any problem involving the allocation of resources, this is related to the institutional network and to the quality of leadership. Hence, the way the conflict between economic prosperity and social deterioration is handled will probably play a key role in the European bet that has been staked by Spanish cities, and more so in the case of the three that have polarized the ‘92 celebrations.

Architecture, in this context, is secondary, but given the reach of the urbanistic operations that are invariably accompanying it, as well as the symbolic importance of some of its products, it is useful as an illustration or an index of the course of events marking the cities of ‘92. The overall picture is, alas, not encouraging. There is no guarantee that the three will usher in 1993 better equipped to compete with Frankfurt, Milan or Amsterdam in the race for material and human resources within European space - this being, after all, the key to the future. Nevertheless, such an assessment cannot be made indistinctively of Barcelona, Madrid and Seville, because each is using this historical occasion in a different way. In all three cases, architecture offers us hints on the direction things are taking.

Barcelona

Endowed with a closed-knit social fabric and a solid identity, Barcelona was an early bird in the race toward ‘92, initiating the necessary large-scale urbanistic projects long before even being designated as Olympic site. Already during Serra’s mayorship, working from Town Hall, Oriol Bohigas drew up the general lines of an urban policy based on his slogan “sanitize the center, monumentalize the periphery” and the decision to use the then still only hypothetical designation as games venue to address metropolitan structural problems from four key areas, among which the Olympic Ring of Montjuïc and the Olympic Village at Poble Nou. So it is that a year before the great sport event, most of the infrastructures are already finished, and the rest are progressing with no other incidents than the expected institutional skirmishes.

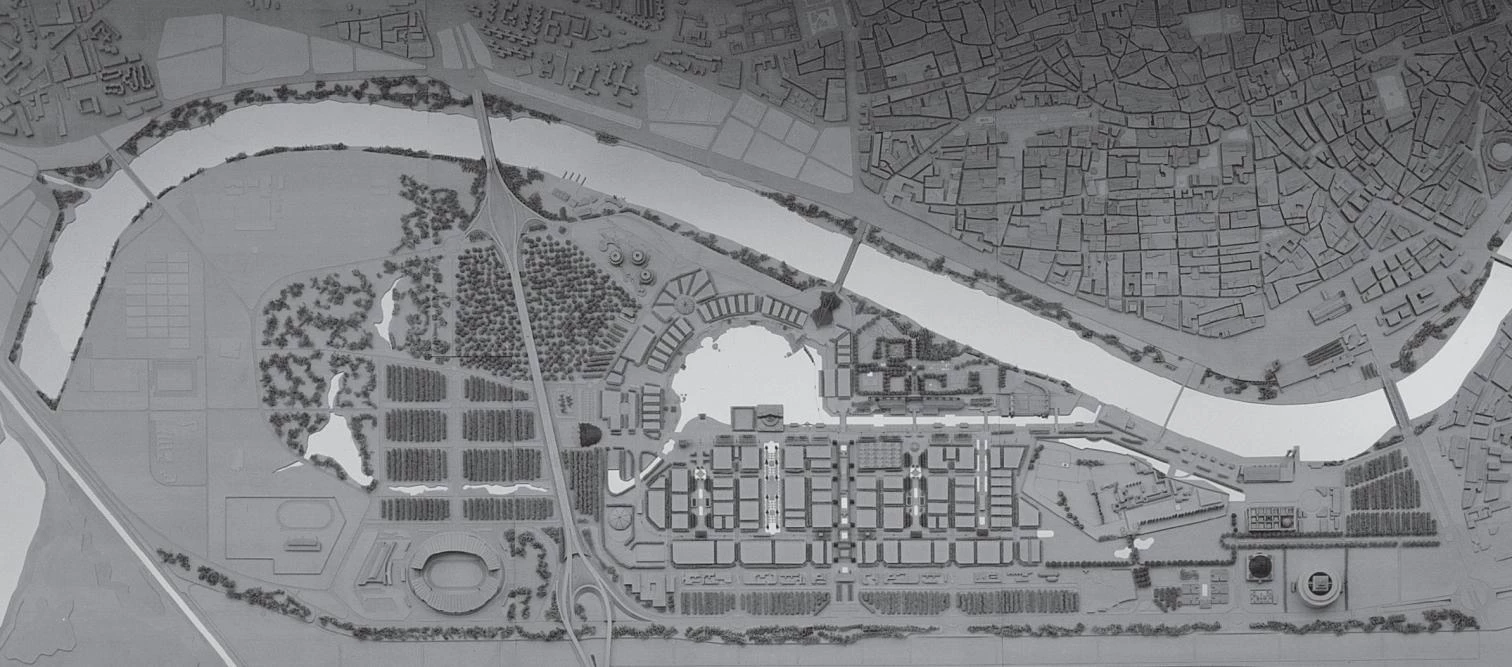

Madrid has offered developers public land in the Campo de las Naciones (below) and in the ‘green corridor’ (above). In Seville, the Expo runs the risk of hindering the city’s urban growth.

On the other hand, the policy of international competitions or direct commissions for public buildings has turned the city into a Mecca of architectural culture. Isozaki, Gregotti, Foster, Aulenti, Siza, Meier and Gehry are only some of the stars who are currently building in Barcelona - alongside, logically, all the big Catalan names, and, in the name of integration, even Madrid professionals like Rafael Moneo. The calculated sacrifice of consistency for prestige will make the Barcelona of the nineties an exceptional architectural zoo with a good share of prima donnas.

Intellectual and administrative leadership, strategical planning, architectural quality... Barcelona has important stakes at hand, but perhaps lacks the most important: money. Whether it can gamble without the risk of incurring unsustainable debts, and without overdoing the game of playing victim, is something only time can tell.

Madrid

In contrast to the sensible dynamism of the Catalonian capital, the State capital sails adrift, shaken only by the onslaughts of private capital, both local and foreign, which uses the city as a real estate piggy bank. Paradoxically, public initiative has less protagonism in Madrid than in other Spanish cities, surely less than in Barcelona. With the shining moment of Mayor Enrique Tierno Galván and his urbanistic right-hand man Eduardo Mangada a thing of the past, municipal teams have seemed determined to auction off the city (a mechanism also tried out in Barcelona, but less enthusiastically), offering developers public land in large operations like the Campo de las Naciones between city and airport, or the ‘green corridor’, which connects the stations of Príncipe Pío and Atocha.

So far, Madrid’s designation as 1992 culture capital has inspired only the idea of an emblematic building for the purpose, and the only thing we have been told about it is that it will have to be “spectacular.” Meanwhile, growing chaos in the streets has forced the president of the government to step down into an arena he hardly frequents and propose what has been called the ‘Felipe Plan’ for the decongestion of traffic. Though this show of concern for domestic affairs may have an endearing effect on a president ordinarily more interested in macroeconomics, the fact remains that meddling with the competencies of the city’s transport boards is not congruent with eluding participation in the major decisions involving the symbolic architecture of the democratic regime - such as the enlargements of the Congress and Senate buildings. In any case, barring the rare exception in a public building or social housing block, Madrid architecture is currently so precarious in health, mediocre in realizations and inanimate in debate that one cannot put all the blame on the absence of political push. Azca’s little Manhattan, on Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana, will continue to grow, with a new skyscraper shooting up each year, and as far as proud contributions to the 1992 jubilee go, in Madrid this is probably as good as it gets.

... and Seville

Again unlike Barcelona, where the Games and the attendant rhetoric have permeated the popular spirit, the Andalusian capital has its back turned to the Expo, or better said, the Expo has its back turned to the city. With Seville’s energies paralyzed by a combination of political conflicts and a very peculiar social mood, the team led by Jacinto Pellón has gone about organizing the World’s Fair as if it were some oil rig in the Caribbean.

Self-sufficient, hyperactive and self-withdrawn, the Expo advances swiftly, though nobody really knows where to. Rising on the island of La Cartuja, the last large chunk of open land in the vicinity of the old quarter, it runs the risk of cramping the city’s future growth by imposing the scheme of a theme park, one closer to a permanent Disneyland than to an urban support that would be of any use in 1993. A product of frustrated competitions, disparate projects, misunderstood pragmatism and rushed decisions, the Expo can end up being anything at all, the only sure thing being that it will have cost a fortune.

The architects and engineers busy building on the island are generally outsiders, from Madrid and a Catalan or two, but few will leave their masterwork there. Sevillians are hardly taking part in the large operations, true to a mutual unawareness between Expo and city, and so far the same goes for the foreigners, who we assume will build their national pavilions; although some time ago Aldo Rossi promised to build a small floating theater on the Guadalquivir...

This Expo is not likely to enter the annals of architectural history the way others did. But it could well perform a service to the city, if the isle of La Cartuja takes the burden that the expected millions of visitors could throw on the delicate fabric of Seville’s old quarter. After receiving 200,000 Pink Floyd fans, Venice learnt all about this. If only Seville could profit from that experience.