Sacred Art

The most recent generation of museums, reaching as far as the Persian Gulf shores, supplies new temples for the worship of art, the ultimate religion of our times.

In an agnostic world, art is the ultimate religion. Beyond the fractures between confessions, art presents itself as a universal creed. Its priests are heard with reverence, its liturgies are followed with devotion, and its temples colonize the planet in the midst of unanimous fervor. The skeptics argue that these temples are governed by merchants, that the commerce of artistic relics is but a branch of the tourist industry, and that art’s ceremonies are part of the propagandistic pomp of power. Yet apart from the fact that all this goes for conventional religions as well, few can deny that art re-connects us through a shared calendar of saints, the communion of spectacle, and a sacred Esperanto. Also, although it creates gods and heroes the way movies, music, and sports do, the inscrutability of its scriptures fabricates a halo of mystery that is nourished by the industry of its interpretation, that organizes its faithful in a hierarchy depending on degree of initiation, and that promotes social stratification with the accumulation of symbolic capital in the realm of magical thought. The conjunction of media populism and mystery elitism makes art an appropriate religion for these times of globalization and inequality.

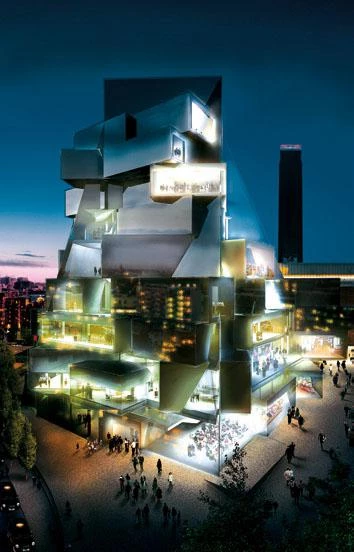

The popular success of London’s Tate Modern has brought about a new extension project designed by the original architects, Herzog & de Meuron.

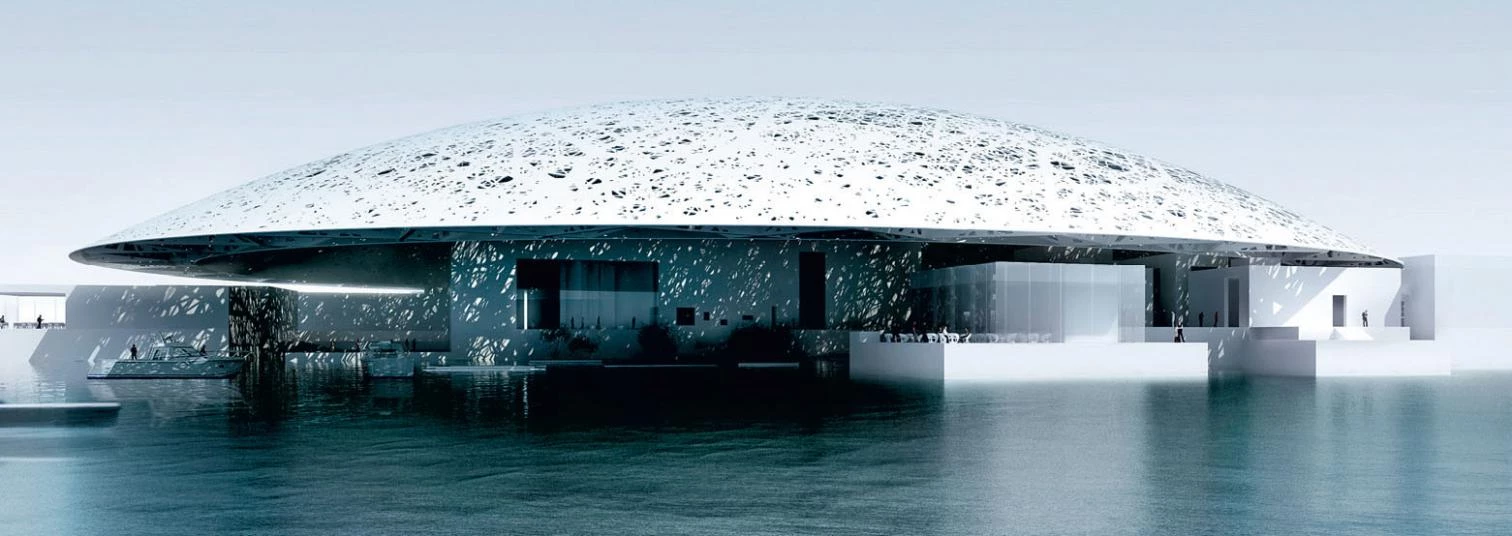

Promoted by economic or political power, the art’s churches know no cultural frontiers, and their theology of creative ecstasy spreads beyond the limits that separate the different varieties of the faith. These days we celebrate the Pompidou’s thirty years and the Guggenheim-Bilbao’s ten with the unction that foundational anniversaries deserve, and these commemorations coincide with a sizzling of news that prove the resounding success of both institutional trademarks, which are multiplying the influence of their mother houses through a proliferation of branches and franchises scattered throughout the globe. The Pompidou, which is opening a new site in Metz in 2008, has another one planned for Shanghai in 2010, after linking up with a Las Vegas company of casinos to set up a center in Singapore and with the Guggenheim Foundation to launch a project in Hong Kong. The Guggenheim, which saw its second New York seat go down the drain after 9-11, failed with its ephemeral branch in Las Vegas, and never managed to materialize its projects for Taiwan and Rio de Janeiro, has revived the missionary zeal that produced its premises in Bilbao, Berlin, and Venice through new sanctuaries of art in Guadalajara, Mexico, and Abu Dhabi in the Gulf.

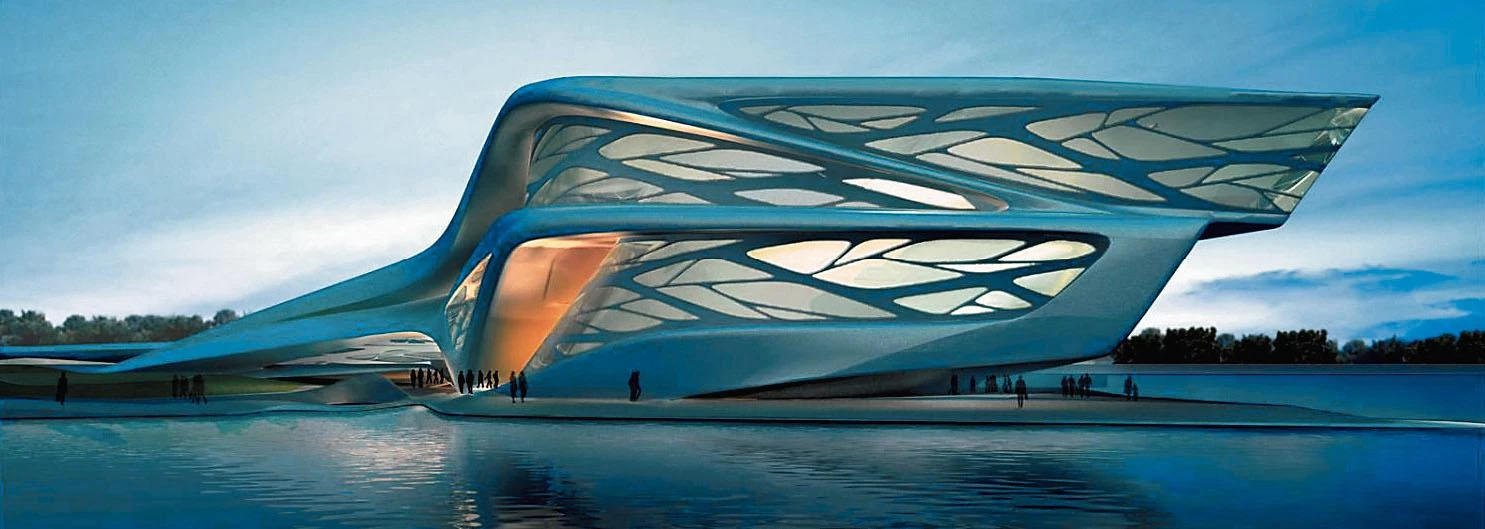

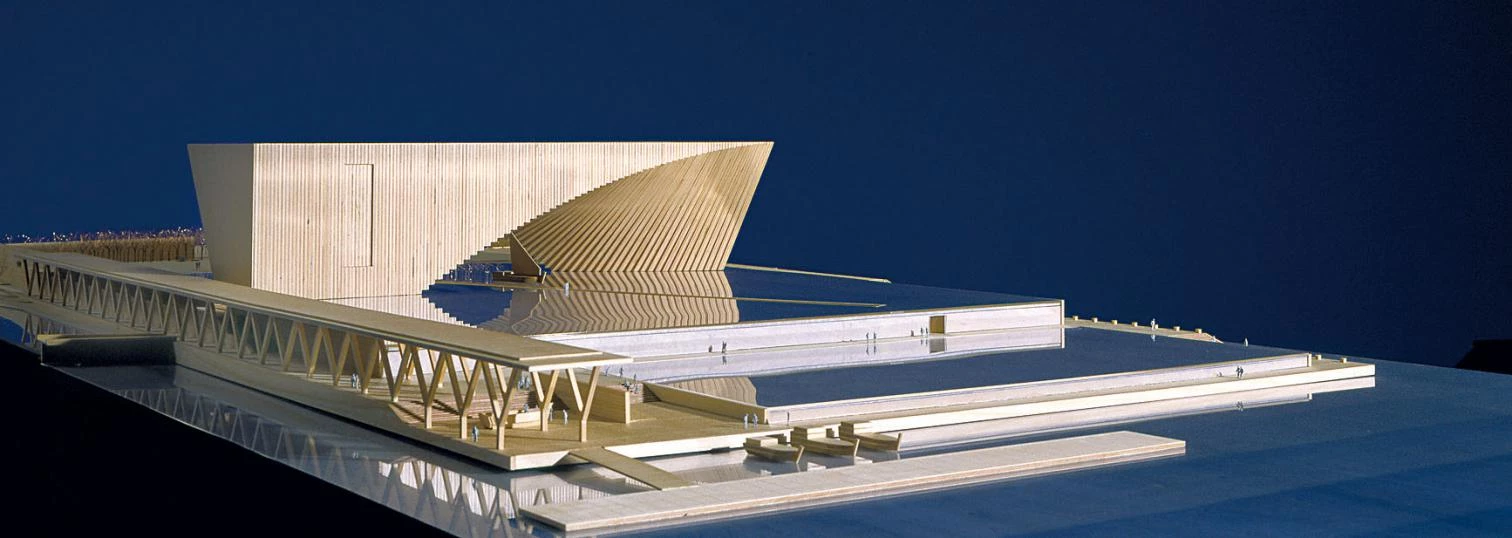

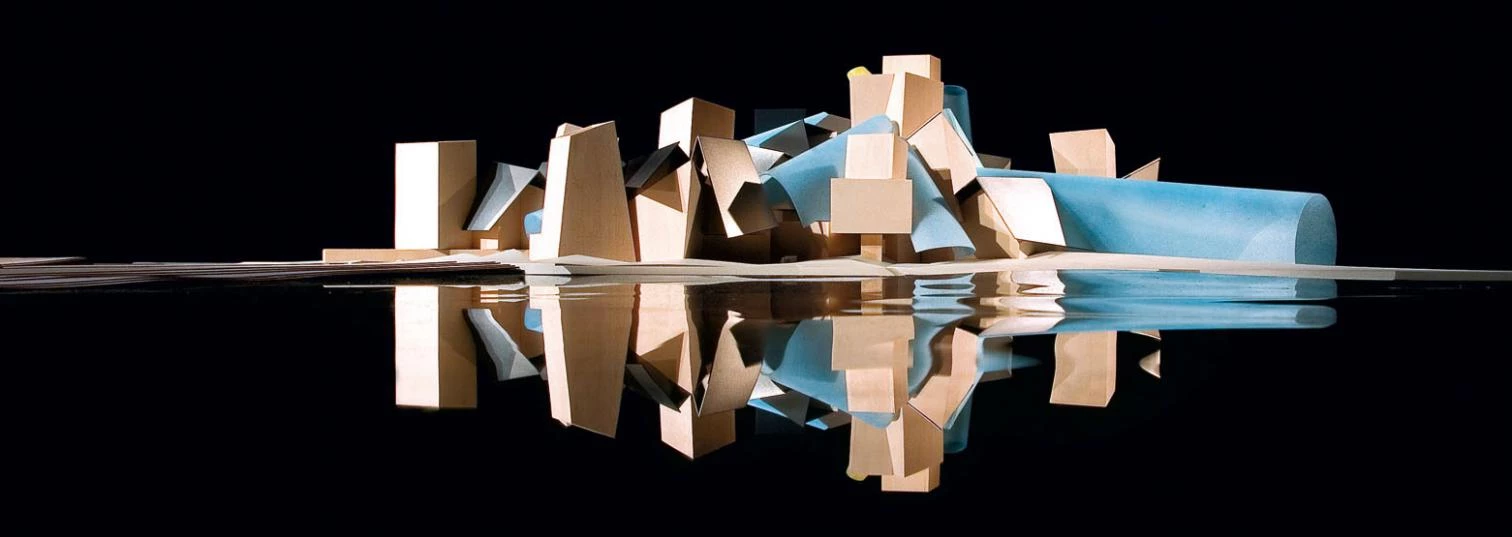

The new Pompidou in Metz by Shigeru Ban rivals in spectacularity with the latest projects for Abu Dhabi, from the auditorium by Zaha Hadid to the museums by Jean Nouvel, Tadao Ando and Frank Gehry.

This last case is revealing, because the Islamic faith of the emirates has not prevented the most prosperous of them all, in its symbolic struggle with real estate and financial Dubai, from resorting to the syncretic religion of art to promote itself, both through the sacred condition of imported institutions and through the shamanist aura of the artist- architects who will be building centers of pilgrimage there. Frank Gehry will of course be the author of the Guggenheim of the desert. Jean Nouvel will build the branch of the Louvre that has sparked the most recent scandal of the hexagon, after the peaceful acceptance of the satellite in Lens and the objections to the long-term loans agreement with the High Museum of Atlanta. Tadao Ando will be doing a sea museum. And Zaha Hadid, a performing arts center. Incidentally, Hadid and Nouvel had been the ones chosen for the aborted Guggenheims of Taiwan and Rio, and Ando and Gehry the rams in the confrontation of the two controversial magnates of French luxury, Bernard Arnault and François Pinault, who used them for the mausoleums that house their art collections in Venice and the Bois de Boulogne. These architects, high priests of the new creed, are called in everywhere to produce cures or miracles, and we can more or less complete the list of sorcerers by adding the Rem Koolhaas of Las Vegas, the Sejima & Nishiza-wa of Lens, the Renzo Piano of Atlanta, and the Herzog & de Meuron of the Tate.

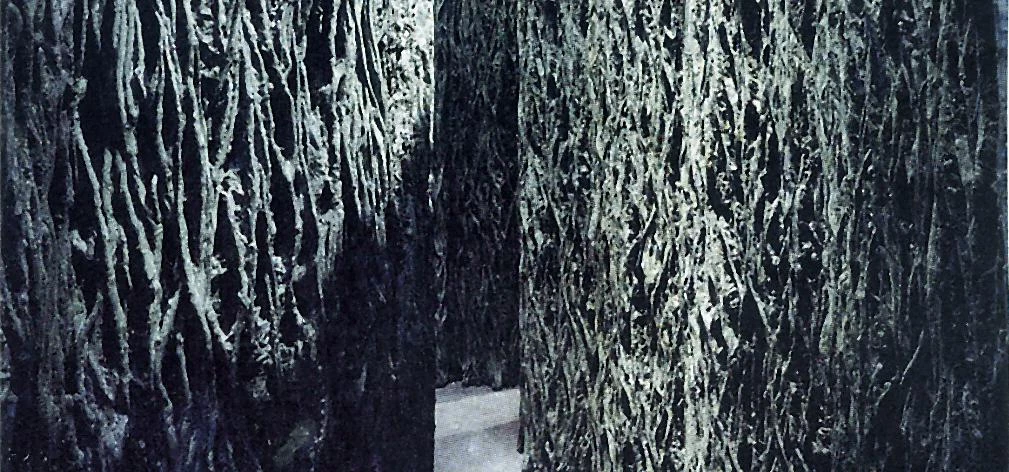

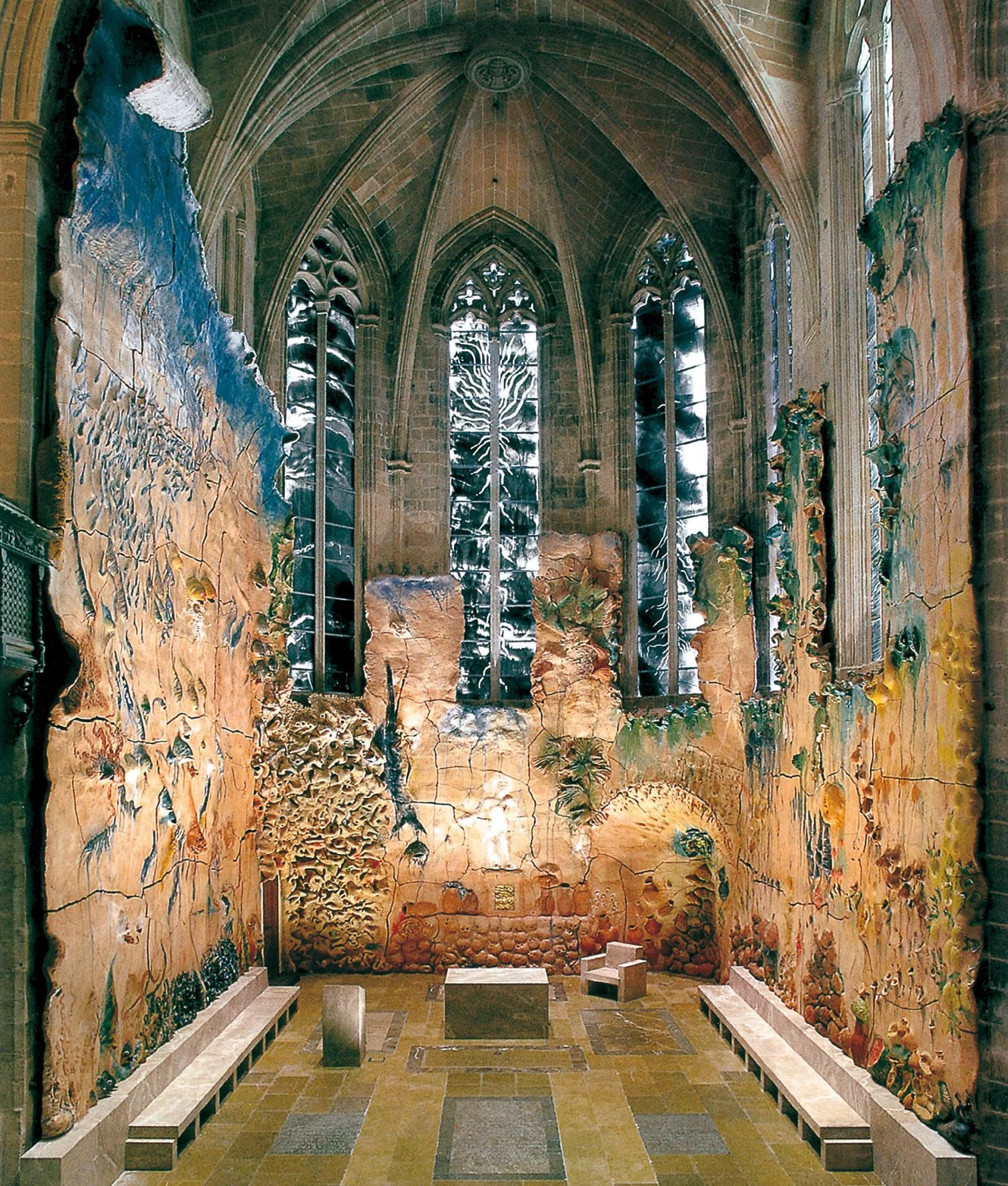

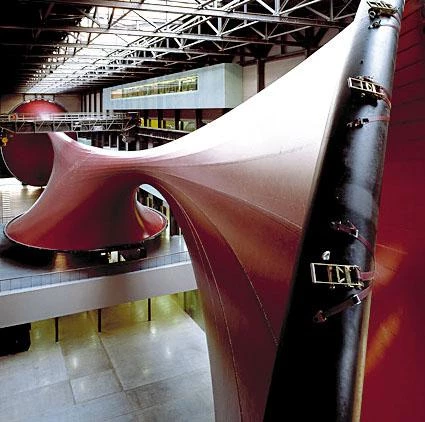

The monumental doors by Cristina Iglesias in the new Prado or the chapel by Miquel Barceló in the Palma cathedral try out a dialogue between art and architecture that also occurs in the installations of the Tate’s Turbine Hall.

In Spain, the Gothic Santiago Calatrava and the classical Rafael Moneo are the leading officiants in the demanding rituals of art, and both have fleetingly appeared in the radars of the present: the Valencian architect – who has yet to build the cathedral he perhaps deserves, unless we hold as such the expiatory temple that is currently materializing in the form of a transport terminal at Ground Zero –, after the King and Queen’s inauguration of Calatrava’s polemic and monumental sculpture along Palma de Mallorca’s seafront, the echoes of which have been overshadowed by the simultaneous opening of the chapel by the artist Miquel Barceló in the cathedral of the same city, a dazzling exercise material representation, theological perplexity and architectural deafness; and the Navarrese – who for his part has indeed built a cathedral, although the Catholic temple in Los Angeles may not reach the heights of inspiration of some of the churches he has dedicated to the worship of art –, with the installation by the sculptor Cristina Iglesias of colossal bronze doors in Moneo’s extension of the Prado Museum (“the world’s most important lay cathedral,” in the words of Iglesias) that the architect has carried out around the cloister of the Jerónimos church. These two simultaneous events prompt us to comment on the Spanish version of the universal fusion of architecture, art, and the sacred.

Neither the sculptor-architect Calatrava nor the painter-ceramist Barceló reach the degree of transubstantiation of matter into spirit that the mystic of art demands, but both the gymnastic balancings of the former and the submarine magma of the latter will be widely admired and therefore prone to be consumed by the midcult of popular piety. The bones and spines of one are as recognizable as the fish and skulls of the other, and this soothing figurativeness matters indeed more than Calatrava’s narcissistic exhibitionism and more than the deaf-mute dialogue between Barceló’s crackled tapestry and the Gothic edges it attaches itself to like an excrescence of mud that is more scenographic than abject, a cacophony charitably muted by the somber grisaille of the stained-glass windows, not to mention his self-portrait, naked like the resuscitated Christ, which refers to the ostentatio genitalium without the benefit of the doctrinal support that the renaissance iconography studied by Leo Steinberg could provide.

In Madrid, for their part, the architect Moneo and the sculptor Iglesias also fail to achieve a happy marriage between construction and art, however much the quiet historicism of one and the vegetal braidings of the other are sure to receive the kind and courteous applause that will make the very delayed inauguration of the extension more peaceful than the project’s troubled history would lead to expect. Moneo’s decoratively striated classicism in brick will reassure those who feared radical geometries in this aristocratic quarter, and yet abrasive abstraction would probably have been the best backdrop for the splendid bronze screens, so charming in their romantic forest fantasy, recalling fairytales or the magical landscapes of The Lord of the Rings, and heirs of a heroic tradition of sculptural doors that includes Ghiberti and Rodin, but also Giacomo Manzù.

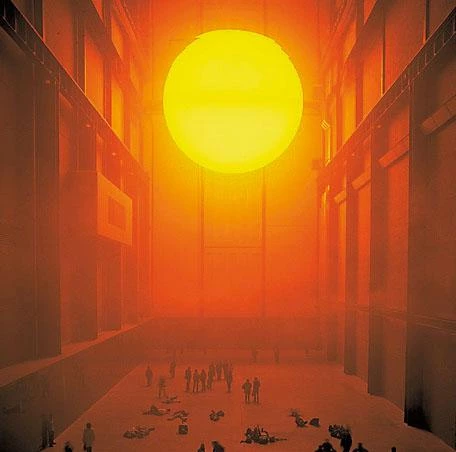

Inside the Prado, the liturgical uncertainties of the new religion at this stage of transition are manifested by the paradoxical coincidence of the sublime Tintoretto exhibition and the extravagant show of photographs by Thomas Struth, dispersed among the canvases of the museum’s collection; a programmatic oxymoron illustrating the indecision and anxiety of a priestly class that has yet to learn to administer the sacraments of a new transversal faith, one that is hidden in the blind vaults of corporations, in the hermetic halls of business parks, or in the remote residences of plutocrats, but is at the same time exposed in the mediatic show¬rooms of museums, the touristy comings and goings of biennials, or the crowded confusion of fairs. Such swingings are patent in the largest basilica of the latest art, the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, which after showing Louise Bourgeois’s spidery terrors, Juan Muñoz’s psychiatric labyrinths, Anish Kapoor’s luminous flaying, Olafur Eliasson’s solar flush, Bruce Nauman’s loud desolation, or Rachel Whiteread’s frozen territories, now has finally found its ceremonial model in the festive excitement of the amusement park, with Carsten Höller’s five slides, accessible to visitors, now occupying the space reserved for the installations of the Unilever Series. The at once intimate and public hallucinogenic thrill of sliding down this roller coaster of sorts mimics the mystic or erotic ecstasy of conventional religions, and offers an intoxicating, quivering precipitate of sacred art, at once leisure for the masses and opium for the elites.