There is a cure for the Prado, but the real solution lies in leaving the cloister alone and filling up the crater. To enlarge the museum, it is not necessary to colonize the cloister of the Church of the Jerónimos. As several proposals have at one time shown, the large-scale excavation that was carried out between the main building and what is now the Ritz Hotel will suffice. Recuperating the original topography in this manner creates a generous yet barely visible volume that can address the functional needs of the Prado in a way syntonizing with Juan de Villanueva’s initial project, and substantially improves the urban environment by smoothening the slopes that rise abruptly from the level of the Paseo del Prado to the Church of the Jerónimos.

The northern facade of the Prado Museum before executing the excavation, in a drawing by Vargas – lithographed by Camarón in 1826 – and a painting by Brambilla of 1820.

The excavation undertaken more than a century ago by Francisco Jareño in order to light up the basements successfully increased the museum’s usable floor space, but at the cost of ruining the topography of the zone, distorting the building’s north facade, and denaturing Villanueva’s essential idea, which was to solve the problem of the avenue’s slope through two floors with independent accesses on different levels. With this clever arrangement, the neoclassical architect positioned the entrance to the lower story at what is now the Murillo door, facing the Botanical Gardens, and the entry to the upper galleries at the current Goya door, whose monumental portico would after Jareño’s excavation absurdly come to rise seven meters above ground level.

The historical sequence shows how the first staircase was added to Villanueva’s north facade at the end of the 19th century, and how it was later substituted in the 20th by that which today conditions the extension.

In any case, Villanueva’s handling of the Paseo del Prado’s grade differences left the internal connection between floor levels unsolved, and this is a matter which none of successive renovations and enlargements have been able to tackle with efficiency and grace. Jareño’s leveling operation only served to externalize the ambiguity, manifested on the north facade by a monumental stairway finished in 1881. This would give way half a century later to a more compact one built by the architect Pedro Muguruza between 1943 and 1946,which is now responsible for the unusual appearance of the Goya door, with its two disconcertingly superposed accesses. It is mainly this relatively recent staircase, deemed untouchable by the guidelines of successive architectural competitions for the museum’s extension, that prevents the Prado from stretching in the direction it yearns to: northward.

The current polemic surrounding Rafael Moneo’s project borders on the insane. In the first place, Moneo’s project is not Moneo’s project, but the project of the museum’s trustees. It is utterly surprising to see how its patrons can leave the architect alone, in front of a hostile public opinion, to defend a project that belongs more to them than to the Navarrese. In the initial competition, the brief was such that any immediate logical solution such as the one described in this article would have been outrightly excluded, but in the second contest, from whence this new so called ‘Moneo cube’ comes, the board supplied the ten participants with a ready-made project to follow to the letter, one so detailed and defined as to render the competition unnecessary. Out of a totally misunderstood spirit of service, Moneo docilely accepted the erroneous givens, and meekly subjected himself to the thoroughly unpleasant task of giving form to an alien project: he has found penitence in sin.

The historical sequence shows how the first staircase was added to Villanueva’s north facade at the end of the 19th century, and how it was later substituted in the 20th by that which today conditions the extension.

And while public opinion treats him the way Apollo treated Marsyas, Spain’s finest architect has to put up with a Francisco Jurado – battering ram of the Curia and instrument enabling the parish to continue with its prime pastoral task: the exploitation of a parking lot – boasting that he, in the controversy of brick against plaster, has moved the chess piece and now is Moneo’s turn; or Ruiz Gallardón’s regional administration threatening a total overhaul in proposing that the project be reduced from five to four stories, with the recommendation that the top three be glazed; or Town Hall socialists, with great imagination and an even better memory, calling for a ‘public debate’ on the Prado. A crossfire of archdiocese, cultural institutions and political parties, in the course of which Moneo’s main support has turned out to be the state secretary of culture, who thus pays his debt for having led the architect to present the project to the world at a snobbish Madrid club!

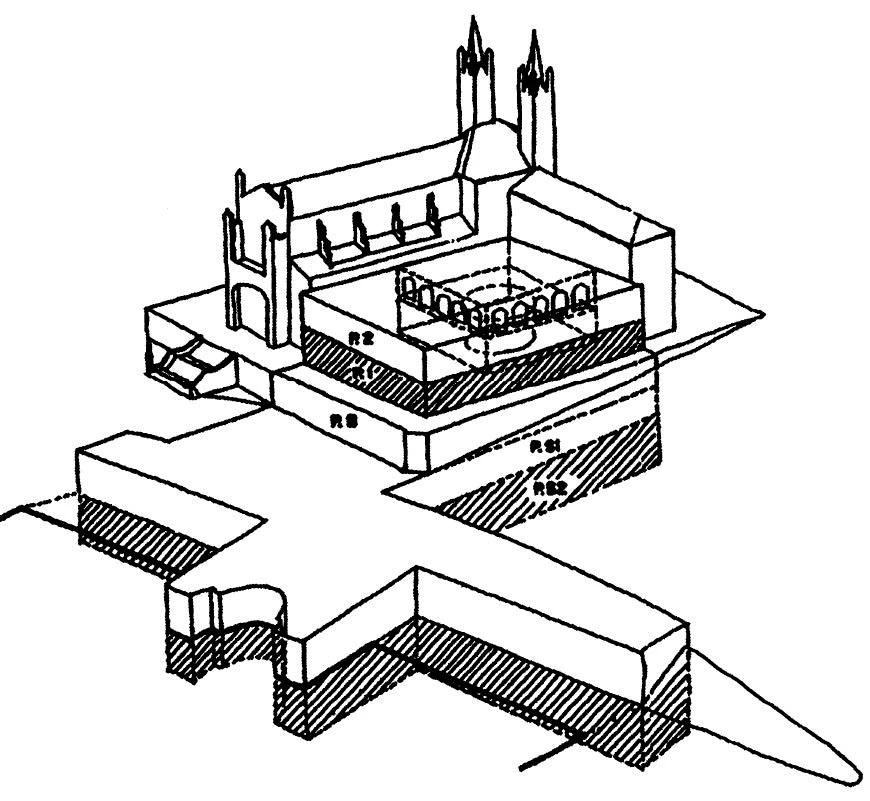

The architects that participated in the second phase of the competition for the Prado Museum extension received from the organizers a detailed outline that left hardly any room for formal or functional alternatives.

n any event, the true culprit is not Miguel Ángel Cortés, despite his unflagging efforts to please President Aznar, who has made the Prado his pet project. Nor is it entirely the fault of the museum director Fernando Checa, a notable historian who no one ever expected to take up full leadership in the management of the institution. The bulk of the blame must fall upon the board of trustees, and if we had to personalize this body in a single individual, it would probably have to be the engineer José Antonio Fernández Ordóñez, who has presided over it since socialist days. Curiously, the government of the People’s Party maintained all three directors of Madrid’s art triangle in office: Fernández Ordóñez in the Prado, José Guirao in the Reina Sofía, and Tomás Llorens in the Thyssen. But whereas it has been smooth-running for the latter two institutions, the Prado has managed to be a permanent focus of upheaval.

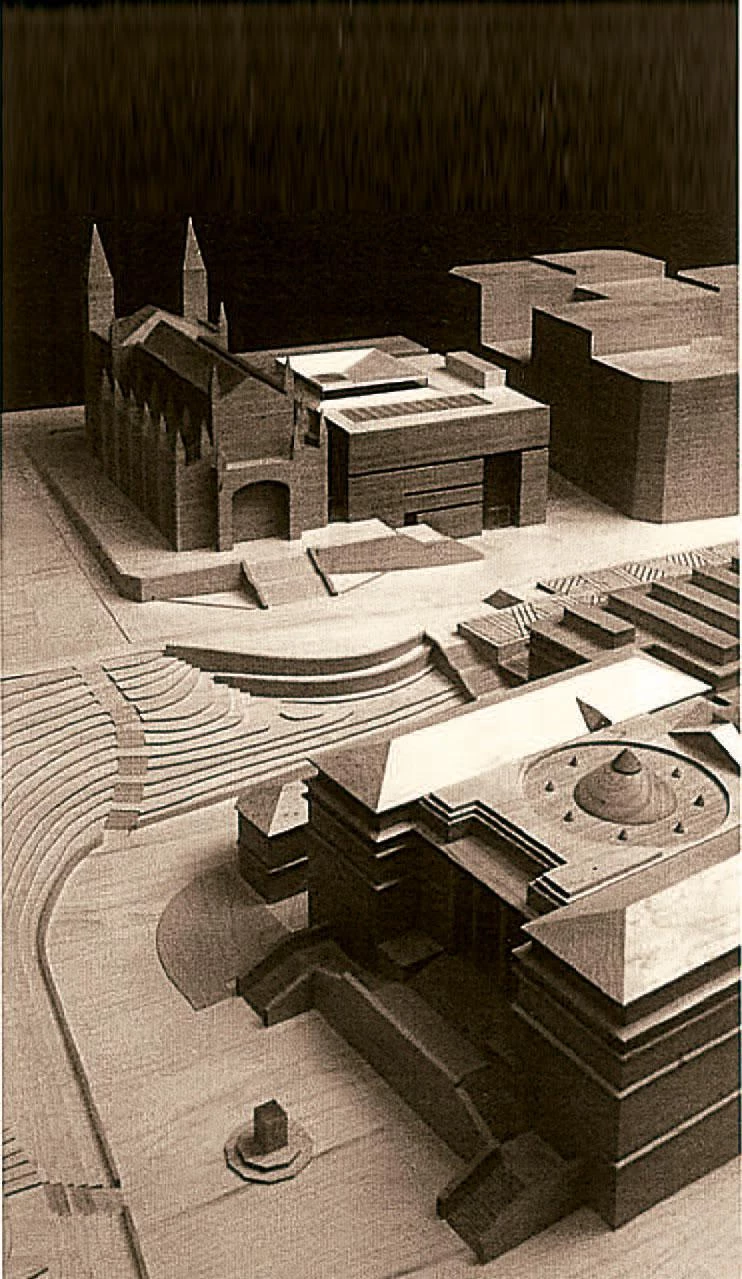

Rafael Moneo’s winning project carefully follows the given guidelines in planning a cube around the Jerónimos cloister, connected to Villanueva’s original building by a semisubterranean volume illuminated from above.

With the current political calendar, the enlargement of the Prado must now wait for the next legislature. Hence, not everything that has been done is irreversible. Even if Aznar stays in office, and even if people in his circle assure him that the prestige of the architect will shield him from the storm of public opinion, the Prado is not the Guggenheim, nor is it the Kursaal. It is not, as it has been said, a project of Moneo, and though true that no one could decorate this ongoing nonsense better than the Navarrese architect, a more worthy work could still be carried out, if only the trustees would lift the limitations established by the guidelines of the competition.

In the project that served as a fuse for it all, the museum’s incumbent curator, the architect Francisco Partearroyo, proposed a northward growth, though he did so with more head than hand, and that possibility was finally banned from the subsequent competition. But many of the participants deliberately defied the guidelines to follow the road traced out by history and topography, and Norman Foster’s extra-competition project developed this option with singular brilliance. Foster knows from his Reichstag experience that buildings eventually become what they really want to be, and in Berlin, by exchanging the canopy for a dome, the British architect simply let himself be guided by the logic of construction and memory. The Prado is our Reichstag, and if they finally allowed him to, Rafael Moneo would do well to listen to the voices of the place, voices which hopefully would lead him from the cube to the pit, and from the cloister to the crater.