The Professor and the Chorus Girl

Moneo Inaugurates the Barcelona Auditorium

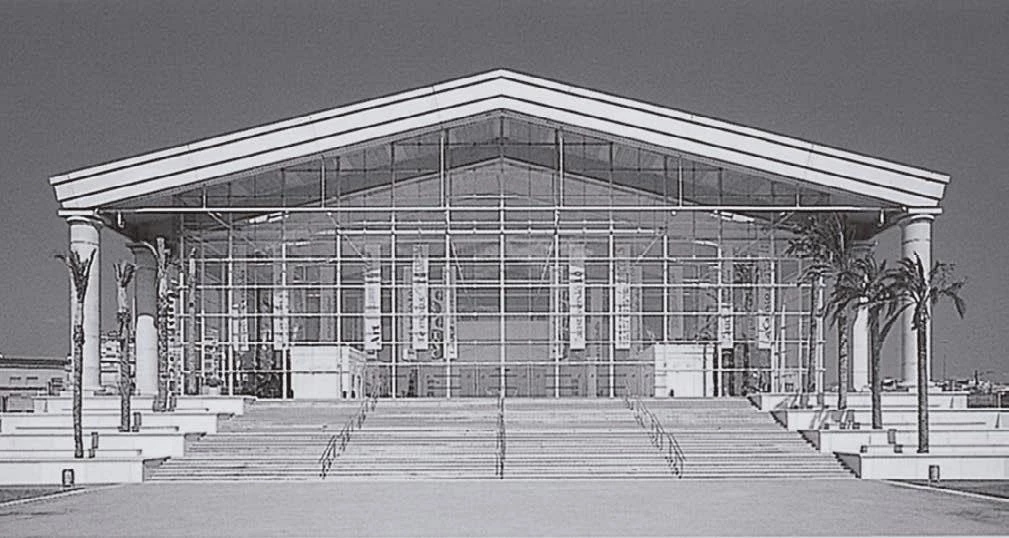

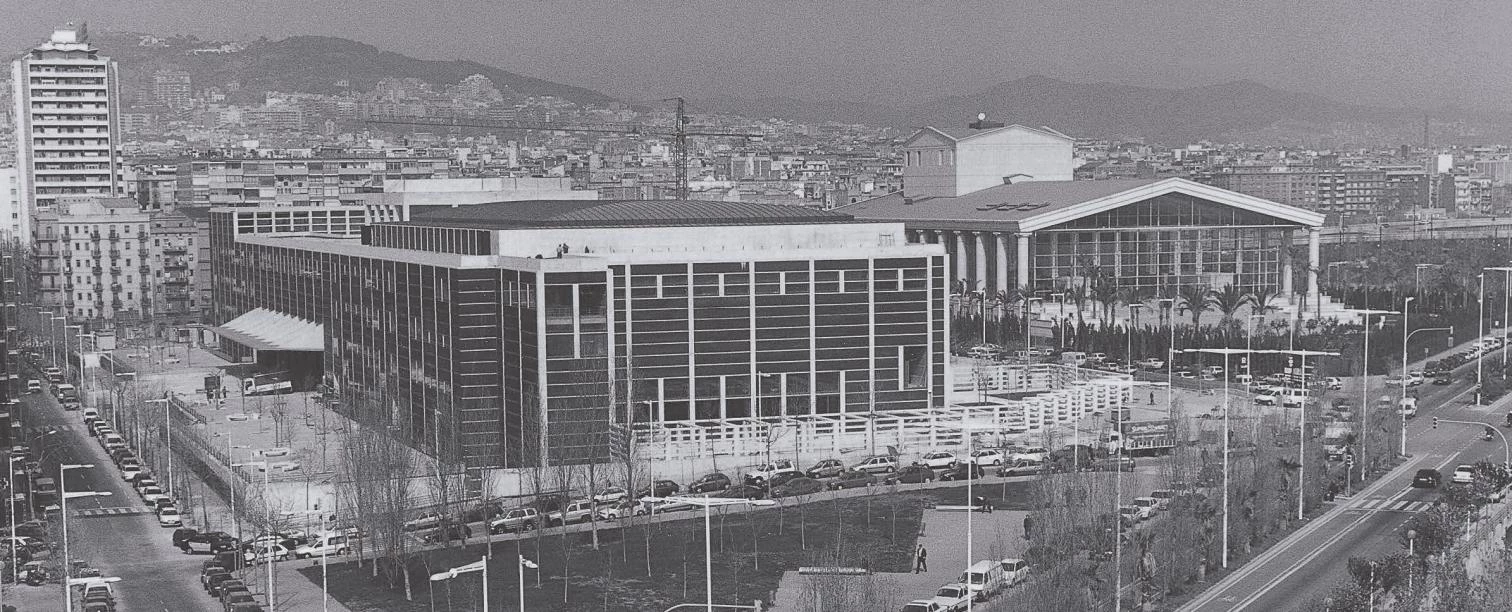

They will admire the professor, but still woo the chorus girl. At the confusing crossroads that Barcelona’s Plaza de las Glorias is, Rafael Moneo’s auditorium has Ricardo Bofill’s theater for a dance partner, and though the buildings seem to ignore each other, they have obviously arrived at the party together. Summoned to solve the encounter between the Diagonal and the Meridiana, a place no longer quite part of the Ensanche but neither as yet belonging to the outskirts, Moneo and Bofill reproduce the encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table. Beside the festive classicism of the theater, cluttered with columns, palm trees and spotlights that form a crossbreed of Hollywood insouciance and Las Vegas ostentation, the severe hermetism of the auditorium’s dark striped box is impressive. This horizontal prism of concrete and steel shelters a music heart of maple wood, but few will prefer the professor’s inner life to the shallow lure of the chorus girl. In this loose part of the city, the whistles of admiration will all go to the blonde.

With a rigorous hermeticism, heir to the dumb boxes of Louis Kahn, the Auditorium of Rafael Moneo distances itself from the festive classicism of the National Theater of Ricardo Bofill.

A rigorous box calls for a more academic environment, perhaps, or at least a better, more consolidated landscape against which, by force of contrast, one can assess its will of abstraction. Here Moneo quotes Louis Kahn and the master’s mute boxes at Yale, but he was probably on the whole unaware that a dumb box cannot compete with a dumb blonde. On the other hand, the Philadelphian built with a precision so exquisite that his details, like Mies van der Rohe’s, must have been inhabited by God. In Moneo’s details lives not so much a god as a mischievous imp, who goes about sprinkling errata in the adjustments between materials, giving the complex a pòvero air in tune with the roughness of the place, even if this may seem somewhat informal by the still surviving codes of concert protocol. Such sloppiness is particularly annoying in the clash between the concrete grid and the meticulous wooden panels that seal the openings on the inside, whose rigorous geometry repeatedly highlights deficiencies in the execution of the structure.

Whereas the concrete deserves no eulogy, the carpentry merits double praise, since the whole in-terior of the building is clad with a warm and lu-minous Canadian maple wood that muffles foot-steps and softens voices, while serving as a support for services that are either skillfully concealed or discreetly exposed, as well as for the elegant signage in Catalan. The friendly splendor of the wood culminates in the symphonic hall, which has the predictable echoes of Scharoun and the precise proportions of a musical instrument, but where ash green seats dissipate one’s illusion of being inside a giant model.

The half of the building that now opens is separated from the volume that contains the chamber music and rehearsal halls by a public foyer. This is a partly covered plaza, crowned by a floorless, ceilingless glass cube that, positioned diagonally with respect to the huge horizontal box, acts as an illuminating courtyard for the galleries of a future museum of music. Moneo resorted to the same Palazuelo who decorated Bankinter’s plaster ceilings a quarter of a century ago, and the artist once again provided geometric patterns, which in this case he attached to the glass walls of the lantern. The result, alas, is as dispensable as that of their previous collaboration, but this does not reflect on the talent of either. Rather, it speaks of the extraordinary difficulty of bringing together the arts in contemporary architecture. In any case, after all, architecture, painting and sculpture in an auditorium are subordinated to music, and the final judgment on the building must be done with ears rather than eyes. Here, at least, there is no doubt to Verlaine’s hierarchy: “De la musique avant toute chose.”