Empty Pedestals

The crisis of leadership in Europe, in the context of an increasingly dangerous world, fuels popular movements that entail both promises and risks.

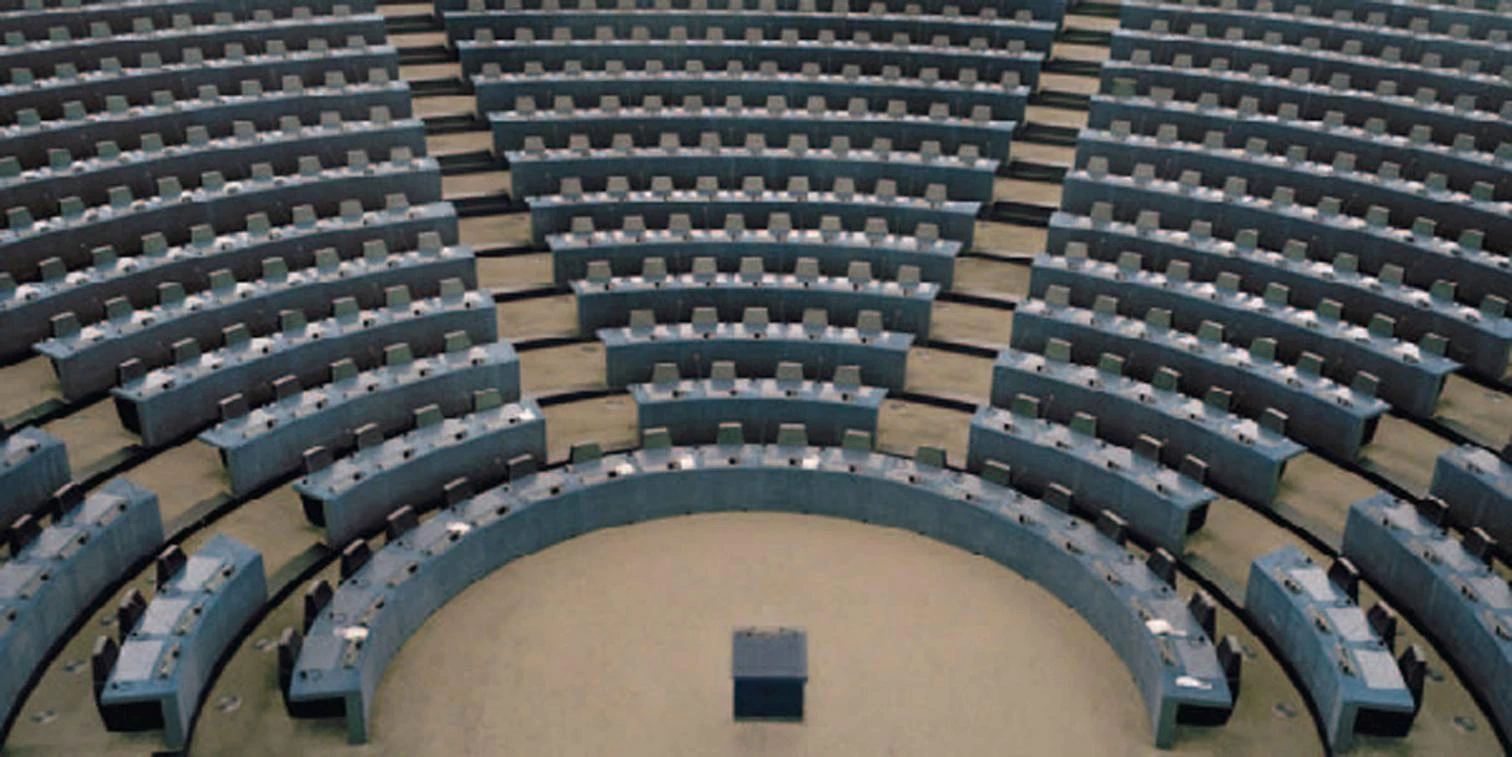

Europe today is a landscape without figures, a garden marked out by empty pedestals. The heroes have abandoned their podiums and wander about in the summer, oblivious to the buzz of the crowd. A century ago, Europe’s leaders acted out a grand guignol that did not prevent the butchery in the trenches, and the continent’s political and economic elites are now again engaged in a senseless ballet around the Byzantine bureaucracy of Brussels. There, the latest elections were perceived as a threat on the system, and not as an expression of the frustration created by casino capitalism and the corruption of meritocracy. In an increasingly dangerous planet, where the USA turns its attention to the struggle with the other superpower in the Pacific, Russia regains a leading role using its energy resources and military power, and the Islamic world accentuates its convulsive insecurity, Europe continues to be a redoubt of privilege, though increasingly besieged by external perils and cracked by internal fractures. Shaken in its representational legitimacy, which has taken on authoritarian features by making democracy opaque and the citizen transparent, and weakened in its territorial cohesion through the revival of divisive nationalisms, the continent faces the storm without captains at the helm to inspire confidence.

Something seems to have gone wrong with democracy, and while we figure out how to revive it, Europe faces a political landscape devoid of the leadership of other times, and a parliament bogged down by indecision.

Most young Europeans are happily oblivious to military conflict, political oppression, or extreme poverty. Most take peace, freedom, and prosperity for granted; few are aware that they are historical exceptions. Almost half a century ago, Rear Admiral Desmond Hoare – director at the time of an international school created in Great Britain by the German educator Kurt Hahn to foster mutual knowledge between young people of different countries – spoke to us who were then his students using an oft-repeated line: “When you have your war…” Fortunately this has not happened, but every generation before us had experienced one, and people of my age who have not had to go through that test know we are unique in this. The Spanish transition was possible because in the mind of its main figures, awareness of the Civil War was still alive, but nowadays it is hard for most citizens to see that peace, like freedom and prosperity, is neither free nor given. In Europe, security has been provided by an American military governance now less alert than in the past, freedom has become associated with liberal democracies that have lost their shine, and prosperity has come from ever more fragile markets.

Such a shifting situation of social mutations, economic transformations, and geopolitical quakes debilitates the web of European solidarity, increasing the vulnerability of each of the Union members, which intensify their distinctive features and interests while watching the hatching of statehood aspirations, a Balkanization of the continent that contradicts its process of integration. François Mitterrand bid farewell in 1995 before the European Parliament in Strasbourg with a precautionary discourse we remember by the phrase he coined as his political testament, “le nationalisme, c’est la guerre,” warning that “war is not only the past, but can also be our future,” and Angela Merkel deserves praise for having repeated the warning as recently as 2013, during a solemn visit to the Élysée.

But she is more the exception than the rule in a panorama of leaders who do not lead, who deal with the crises of institutional legitimacy, demography and society, and territories or nationalism – three crises intensified in Spain to the point of paroxysm – with pasteurized statements or placebo solutions. In this context of paralysis of representative democracy, it is no wonder that movements crop up that are described negatively as populist, but which perhaps can be understood as seeds of a ‘performative’ democracy, to use the term of the Polish sociologist Elzbieta Matynia. Using the philosopher of language J. L. Austin’s performative statements as reference, this form of democracy does not aim for representation, but for transformation of the political arena through citizen participation, something which took place in 1970s Spain, 1980’s Poland, and 1990s South Africa. Capable of stimulating pacific transitions and characterized by dialogue and compromise in the public realm, the performative democracy theorized by Matynia is a message of hope inspired by two philosophers of emancipation “who knew darker times, Hannah Arendt in Nazi Germany and Mikhail Bakhtin in Stalinist Russia.”

The current crisis of representation, manifest in the drift towards power deprived of images – a figurative expression of the disappearance of responsibility – has provoked a wave of social unrest that is at once a risk and a promise, and the murmur of the crowd has pushed charisma towards the margins, highlighting the lack of leadership in the inner core of the political and economic system. The pedestals are empty, and the sleepwalkers roam about in the garden, trying in vain – like Cansinos Assens – “to extend the summer holding it by its tail of moist satin that shines and rips.”