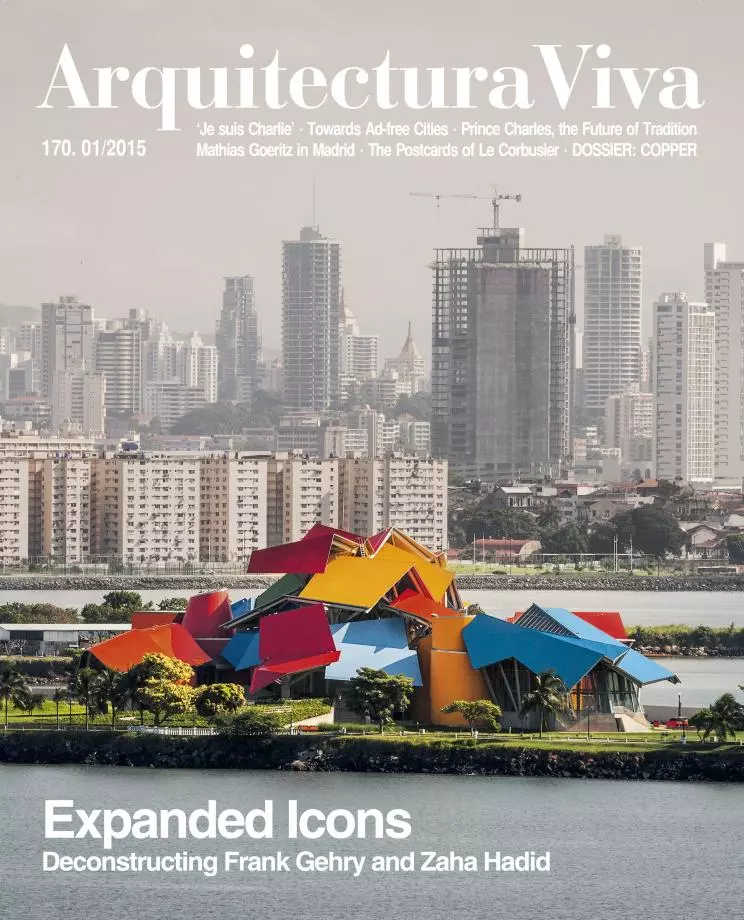

Icons expand, going beyond architectural and geographical boundaries. The new generation of emblematic works breaks through the conventional frontiers of architecture, becoming inhabited sculptures or built landscapes, and also multiplies virally to extend unbridled throughout the planet. These are icons of an expanded architecture whose global expansion generates aesthetic and ethical problems. As far as aesthetics is concerned, digital tools have enabled designing and building sculptural or topographical objects that are hard to understand using the discipline’s traditional tools, because they invade adjacent fields that must be explained with another repertoire of instruments; and in ethical terms, the growth of works of unique expressiveness and cost forces to ponder on whether their use of material and formal resources is commensurate with the financial capacity and the symbolic needs of the communities where they go up.

But emblematic works have always been around, and from the pyramids or the colossi of the ancient world up to Ronchamp, our history is punctuated with iconic constructions that blur the boundaries between architecture and sculpture. The second half of the past century was marked by buildings that left an imprint on each decade: the fifties cannot be conceived without Wright’s Guggenheim, a heroic spiral facing New York’s Central Park; the sixties without the endless construction of Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, with its concrete sails rising over the bay; or the seventies without the cheerful technology of Piano and Rogers’ Centre Pompidou, a multicolor refinery in the Parisian Marais quarter. Three icons in three different continents that expressed well the interests of their time, fostered architectural innovation and became fully representative of their respective cities, even though they stood in sharp contrast with their environment.

The dialogue between architecture, sculpture and landscape has become more intense and muddled over the last decades, despite the efforts of the critic Rosalind Krauss to theorize their mutual relations in an often quoted article of 1979, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ – recently used as guiding thread in a series of encounters between art and architecture published as Retracing the Expanded Field. In fact, what truly extended the field of architecture was the huge critical and popular success of the Guggenheim Bilbao, which Frank Gehry opened in 1997, festively altering the rules of the game with the crucial aid of Catia software, and triggering an iconic deluge which had Zaha Hadid and her partner Patrik Schumacher (who soon proposed ‘parametricism’ as the conceptual support of the free-flowing forms of the Anglo-Iraqi architect) among its most significant champions: in the end, this warped, fractured ground is where our expanded icons stand today.