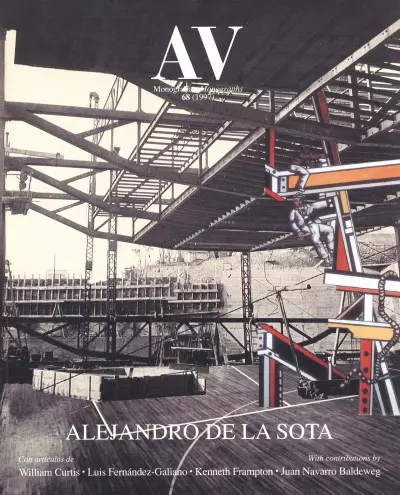

ALEJANDRO DE LA SOTA

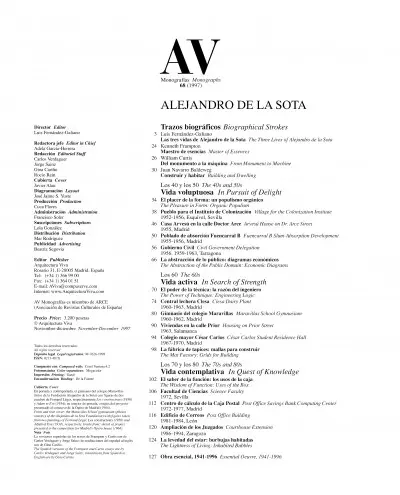

Trazos biográficosBiographical Strokes

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Las tres vidas de Alejandro de la Sota The Three Lives of Alejandro de la Sota

Kenneth Frampton

Maestro de esenciasMaster of Essences

William Curtis

Del monumento a la máquinaFrom Monument to Machine

Juan Navarro Baldeweg

Construir y habitarBuilding and Dwelling

Los 40 y los 50The 40s and 50s

Vida voluptuosaIn Pursuit of Delight

El placer de la forma: un populismo orgánico

The Pleasure in Form: Organic Populism

Pueblo para el Instituto de ColonizaciónVillage for the Colonization Institute

1952-1956, Esquivel, Sevilla

Casa Arvesú en la calle Doctor ArceArvesú House on Dr. Arce Street

1955, Madrid

Poblado de absorción Fuencarral BFuencarral B Slum-Absorption Development

1955-1956, Madrid

Gobierno CivilCivil Government Delegation

1956, 1959-1963, Tarragona

La abstracción de lo público: diagramas económicos

The Abstraction of the Public Domain: Economic Diagrams

Los 60The 60s

Vida activaIn Search of Strength

El poder de la técnica: la razón del ingeniero

The Power of Technique: Engineering Logic

Central lechera ClesaClesa Dairy Plant

1960-1963, Madrid

Gimnasio del colegio Maravillas Maravillas School Gymnasium

1960-1962, Madrid

Viviendas en la calle PriorHousing on Prior Street

1963, Salamanca

Colegio mayor César CarlosCésar Carlos Student Residence Hall

1967-1970, Madrid

La fábrica de tapices: mallas para construir

The Mat Factory: Grids for Building

Los 70 y los 80 The 70s and 80s

Vida contemplativaIn Quest of Knowledge

El saber de la función: los usos de la caja

The Wisdom of Function: Uses of the Box

Facultad de Ciencias Science Faculty

1972, Sevilla

Centro de cálculo de la Caja PostalPost Office Savings Bank Computing Center

1972-1977, Madrid

Edificio de CorreosPost Office Building

1981-1984, León

Ampliación de los JuzgadosCourthouse Extension

1986-1994, Zaragoza

La levedad del estar: burbujas habitadas

The Lightness of Living: Inhabited Bubbles

Obra esencial, 1941-1996 Essential Oeuvre, 1941-1996

Luis Fernández-Galiano

The Three Lives of Alejandro de la Sota

The men of the Renaissance aspired to reconcile pleasure with power and wisdom. According to Platonic tradition, human life was to combine voluptas, potentia and sapientia, and this was the origin of many a humanistic dissertation that recommended the simultaneous emulation of Paris, Hercules and Socrates, or the joint veneration of Venus, Juno and Minerva. In the usual ternary ordering, such insistence on the multidimensional variety of life is occasionally expressed as a desire to integrate the delightful, the practical and the theoretical, in line with the powers of a soul that is allegedly endowed with sensibility, strength and intelligence. These trinities, which will remind architects of the venustas, firmitas and utilitas of the familiar Vitruvian triad, had their canonical expression in the much repeated presentation of the three lives: vita voluptuosa, vita activa, vita contemplativa; three lives which at times appear as alternatives, as they do to Poliphilo in the famous scene that has him choosing among three doors leading to love, earthly success and divine glory, and other times as successive stages, not too different from the archaic three ages of man —ardent youth, active adulthood and reflective old age— which allow one to reconcile diversity by arranging it chronologically. Here it is the latter interpretation of the three lives that serves as a rhetorical device for a narrative orchestration of Alejandro de la Sota's professional biography, a trajectory which is stubborn in some essential convictions but also dislocated at some points by several existential fractures.

This mythical reconstruction of the life of the hero begins with a period dominated by the pursuit of pleasure that beauty provides, in a path that leads from the organic folklorism of the villages to the abstraction of the public buildings in an introverted postwar Spain. The second phase corresponds to the years of economic growth, during which the architect, fascinated by engineering, formulated practical challenges involving the rationalization of construction and the choral anonymity of minimums. In the third and final period Sota pursued the silent wisdom of function with progressively naked and immaterial boxes, in a stripping process that anticipated his own physical disappearance. Premodern, modern and transmodern, the three lives of Sota were three movements of a single score played in the course of half a century.

Son of a military engineer and surveyor from Santander, Alejandro de la Sota Martínez was born "in a stone house" of Pontevedra on October 20, 1913, and cultivated his musical and artistic talents in the favorable setting of a well-to-do and educated family, soon beginning to play the piano and draw cartoons in the manner of Castelao. After two years of Mathematics at the University of Santiago de Compostela, young Sota set forth for the restless Madrid of Republican times to study architecture, only to be interrupted by the break-out of the Spanish Civil War in the summer of 1936. At the end of the conflict, in which he participated on the Franco side, he resumed his studies at the Madrid school and earned his degree in 1941. He was to reside in the capital until his death in 1996 but remained tied to Galicia, where his father was influential as president of the central government delegation in Pontevedra, where family and social contacts afforded him many of his first clients, and which was birthplace as well to admired colleagues like Ramón Vázquez Molezún of La Coruña and to masters like fellow-Pontevedran Antonio Palacios who then had much clout in Madrid.

In Pursuit of Delight

From 1941 to 1947 he worked for the National Colonization Institute, an organism created to plan rural settlements in the newly irrigated lands of a country devastated and impoverished by war. Also a fruit of this long contractual relationship were the villages Sota carried out during the first half of the fifties, where he used the same friendly and organic language of his private house commissions or his office and store renovations. In 1952 he married Sara Rius, a very beautiful young woman who was to give him seven children, and between that year and 1956 he took part in a series of competitions for public buildings whose functional and symbolic requirements geared his architecture toward abstraction. This period of formal preoccupations ended with the project for the civil government of Tarragona, a trip to Berlin that put him in contact with European trends, and his entry in the School of Architecture as a teacher, three events which, combined with the failure of the country's isolationist economic model, sparked a process of critical reflection that led Sota away from formalist esteticism. At the end of the decade, a professional drought prompted him to join the Post Office, becoming a functionary in 1960.

In Search of Strength

The boom of the sixties gave a new impetus to Sota's career. The long postponed construction work in Tarragona finally got going, and in Madrid he supervised the building of the Clesa dairy plant and the Maravillas gymnasium, two projects of an industrial character which allowed him to continue the dialogue with engineering initiated a few years back at the aeronautic workshops of Barajas. On completion of these works he obtained new commissions in Zamora and Salamanca, as well as one for CENIM's research facilities in Madrid, and in 1964 he signed for a leave of absence at the Post Office, eager as he now was to devote full time to his practice. In this climate of social and technological optimism, besides continuing to experiment with large metal spans in sport building projects, he began to explore systems of prefabrication in concrete, which he first tested in houses and later tried to apply in mat residential developments such as those for Mar Menor and Orense. Yet none of these was carried out and his disappointment was aggravated at the end of the decade by two severe blows: the defeat of his Miesian glass prism in the competition for Bankunión, an office building on Madrid's Paseo de la Castellana; and his failure to obtain a chair at the School of Architecture, a let-down which made him abandon teaching altogether.

In Quest of Knowledge

Sota's depression brought him back to the Post Office in 1972, and he would stay in the service until his retirement. During this final phase of stocktaking and introspection his obsession was "the box that functions," a progressively immaterial container that was a continuation of the Bankunión proposal, that was best expressed in two unexecuted projects, Aviaco's headquarters and the museum of León, and which also lay at the base of his two major Post Office jobs, the calculation center of the Caja Postal in Madrid and the Post Office building in León. The same pursuit of functional lightness is perceived in his residential projects of the period, the greater part of which would remain on paper. The twilight years saw public recognition coinciding with physical deterioration and the pain caused by the death of his architect son. Shortly before his own demise on February 14, 1996, Alejandro de la Sota signed his last project for the Maravillas school, a tribute which closed his biography in the place where it had reached its finest moment.