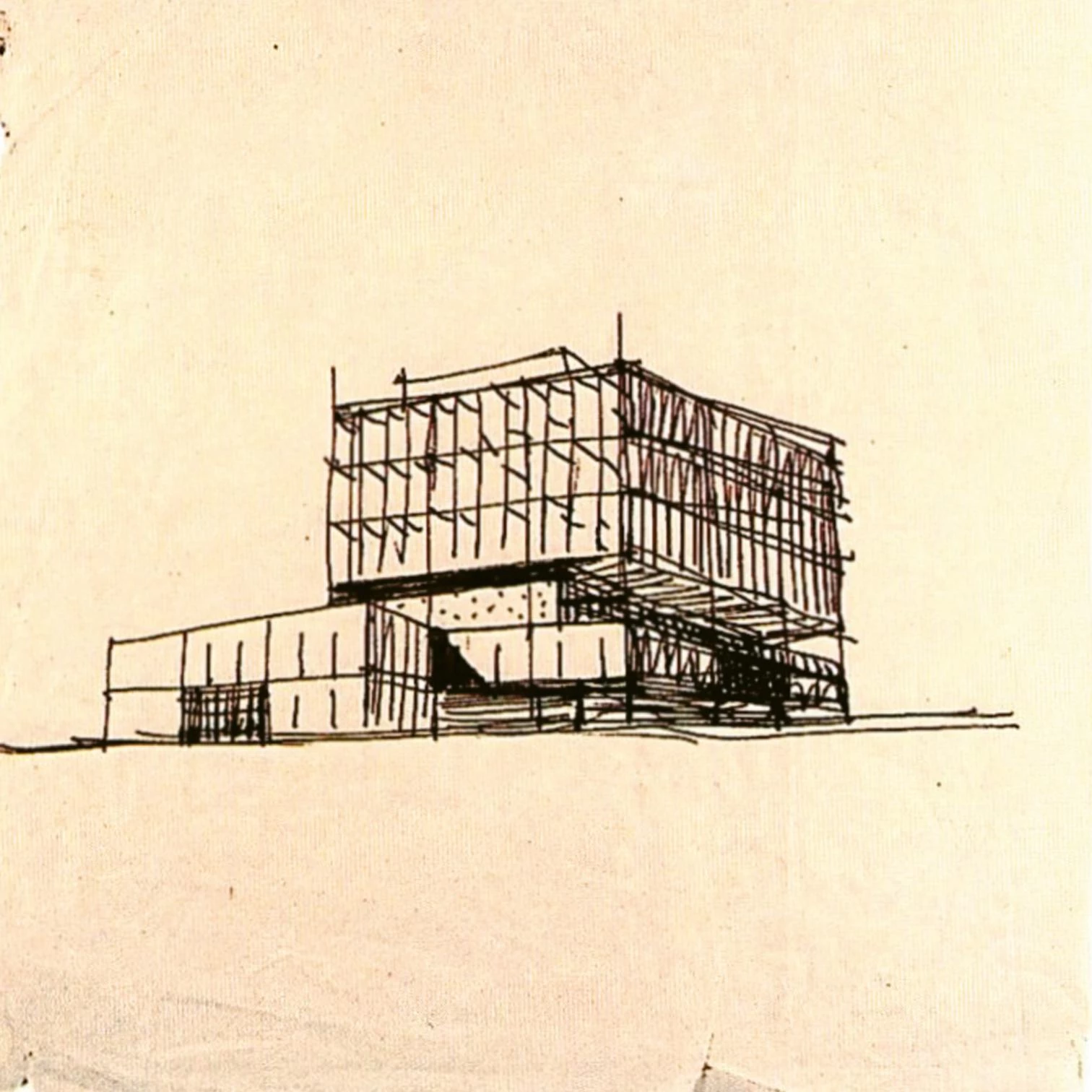

Sota was based in Madrid and lived most of his life here, but he came from Galicia in the northwest of Spain, a remote region with a cold, clear light and a vernacular founded upon sharp granite masonry. When glass was used, it was as a sheet or screen flush with the stone, a planar surface, both tactile and abstract. His mature works had just this quality of materiality and immateriality - as if there were a spiritual presence just beneath the surface of the simple facts of steel girders, plate glass or textured brick. Given this elusive sensibility and his other-worldly temperament, it is not surprising that Sota should eventually have been attracted to the architecture of Mies van der Rohe, which he knew only through books. His own private quest for ‘essentials’ within structure and technology happened to coincide with a growing dissatisfaction in Spanish society with the extreme traditionalism of the Franco regime. While not socially radical (he could be called a ‘mystical conservative’) Sota was radical in matters of art, and thirsted after the ‘universality’ of the major works of the Modern Movement which had been denied his generation in Spain. The sparse planarity and ideal forms of Mies van der Rohe thus took on the character of moral emblems to him: combining a progressive ethos with a spiritual core... [+]