Clesa Dairy Plant, Madrid

Alejandro de la SotaBetween 1955 and 1969 Sota drew up six proposals for dairy centers, of which only the one for Clesa in Madrid was actually carried out. Though he began to work on it in 1958, the final project is dated two years later. By this time the reductive nature of Don Alejandro had already shifted toward a more silent kind of architecture. Ax he stated in the Clesa brief, it was now time for simple containers.

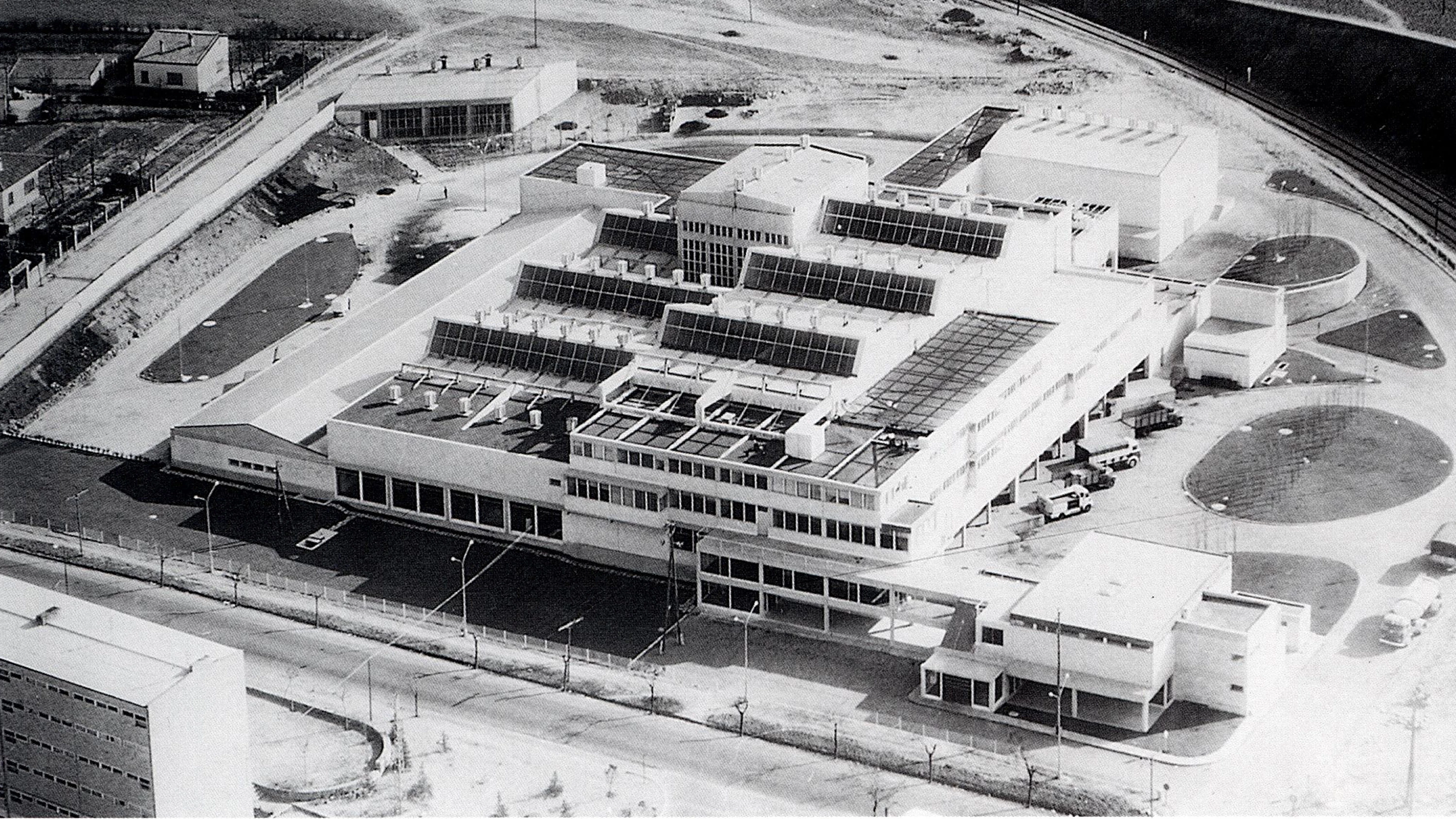

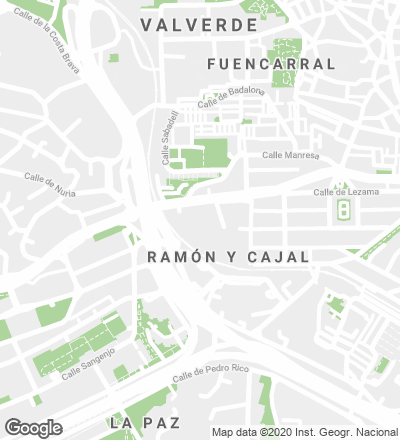

Set in a large industrial parcel of the Fuencarral district, the program is fragmented for hygienic reasons into independent volumes, though these are connected at ground level by glazed walkways. The milk collector facilities are detached from the central shed, which is flanked by the receivers of empty bottles on one hand and the dischargers of bottled milk on the other. The south zone contains the refrigeration chambers and the spaces for storing butter and other byproducts manufactured transversally in the course of the linear milk-elaboration process. It is toward the staff entrance along Cardenal Herrera Oria Avenue that the complex offers its most amiable and urban image. The facade accommodates the offices and the free-standing volume of the dining rooms in a careful balance between the bands of windows and the opaque surfaces, which interlock, superpose and intersect.

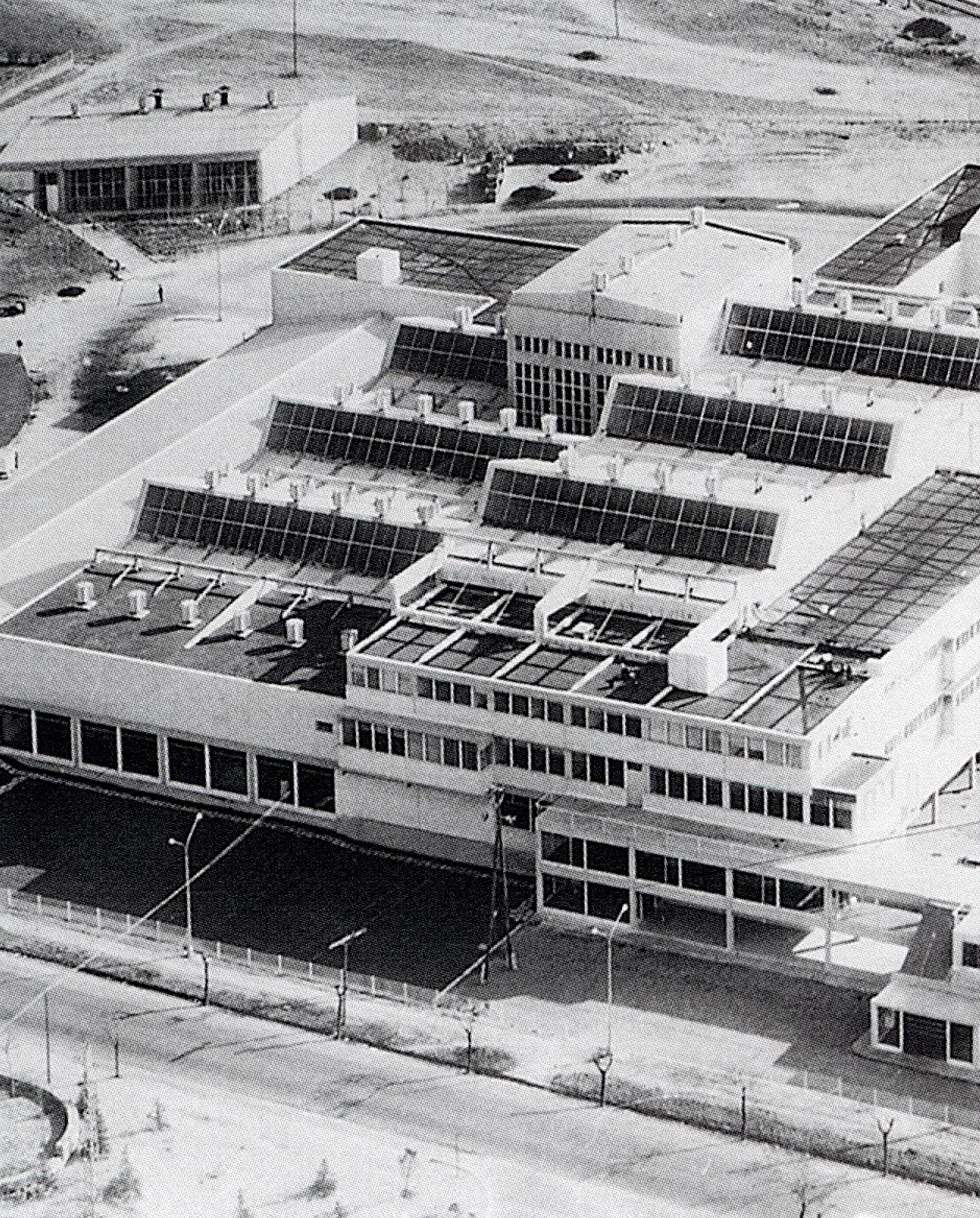

The production space is divided into two zones by the bands of skylights, an exception to which is the prism sticking out from the roof over the sterilization area. Dotted at their summits by rows of electric fans, these long connected skylights mark a directional and rhythmic tempo, in a sequence of broken sawteeth that rest lightly on structural lines. To the south they materialize into a double layer offibercement, including an air chamber and with the Unes of the metal frames lending rhythm to it, whereas the slope of the glazed north zone reaches the height of the sun during the summer solstice, thereby avoiding both the greenhouse effect and direct sunlight.

The iron shortage during those years of incipient reindustrialization made a massive construction necessary, a pretensed concrete structure with steel struts and an enclosure of prefabricated blocks whose chalky appearance stresses the gray Y-shaped pillars. Such a symmetrical main support sustaining another, tighter framework was repeated in the sport pavilion of Pontevedra (1966), which blends the muscular concrete volumetry of the Clesa factory with the lyrical steel one of the Maravillas gym... [+]