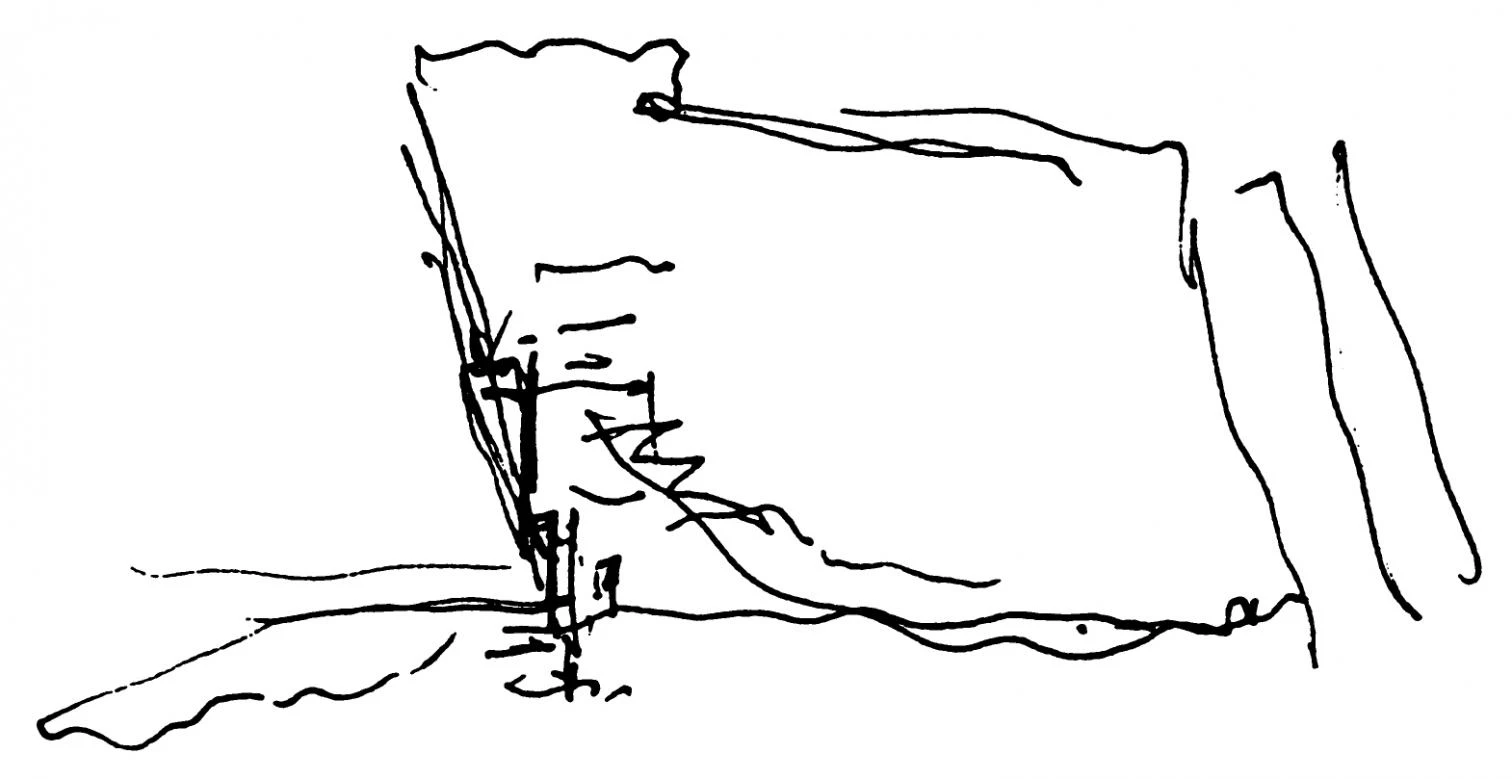

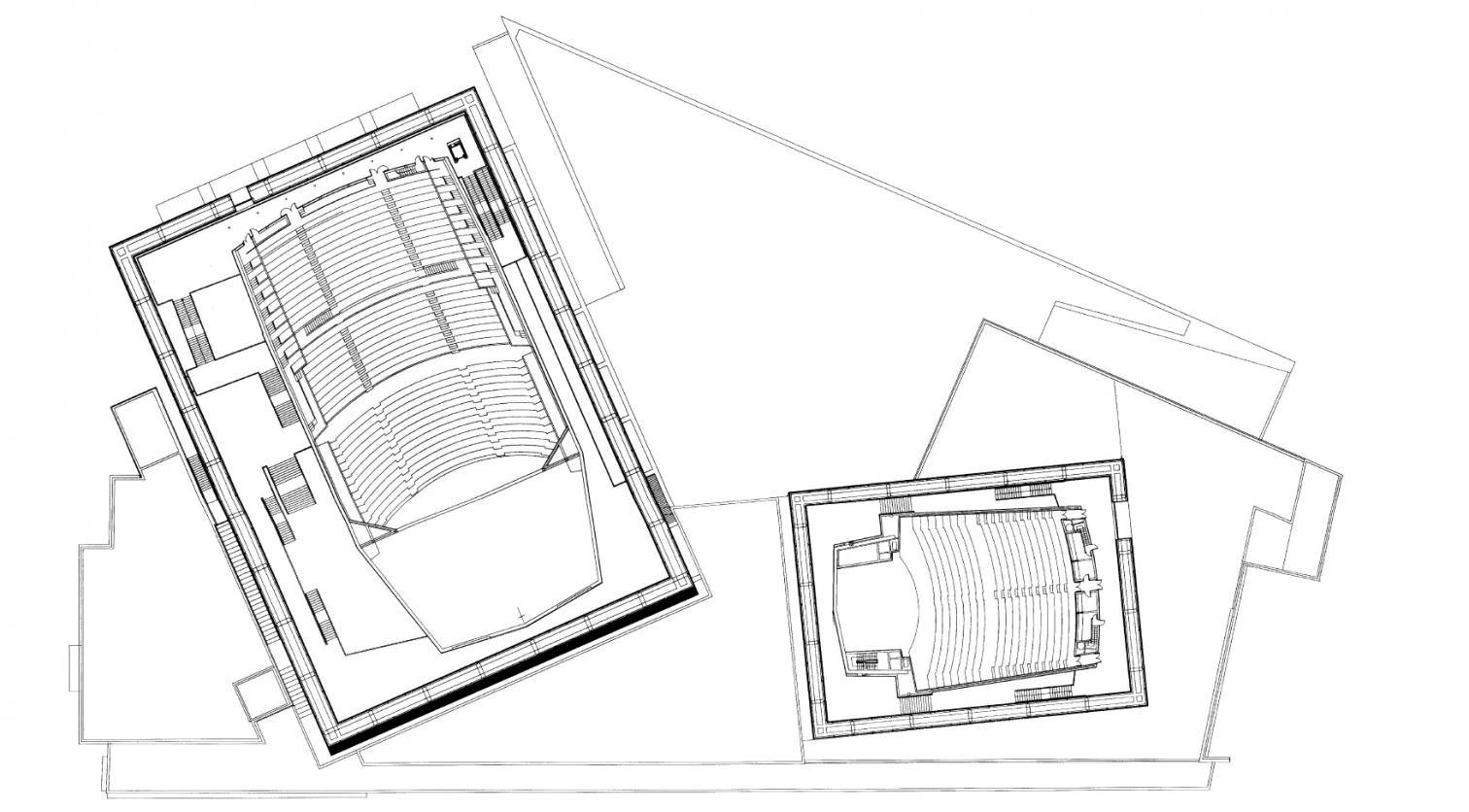

With its leaning, translucent cubes, the San Sebastian Kursaal is Rafael Moneo’s finest project since Mérida, and without doubt the most formally and constructively daring of his large oeuvre.

We dined together on a Saturday. Hours later a staircase caved in at the construction site of the Kursaal auditorium in San Sebastián. That Sunday, April the 20th, marked the first setback in the career of the architect Rafael Moneo. Over dinner we had been discussing Benjamin of Tudela, the famous Jewish traveler who in the 12th century had scoured the Near East, a region Moneo frequents of late to supervise the building of Beirut’s Bazaar, and in the next few days he took time off the eddy of commitments triggered by the collapsing to send me a Hebrew, Spanish and Basque edition of his distant compatriot’s book of voyages. The theologian brother of the architect Peter Eisenman refers to Benjamín de Tudela in his monumental and heterodox James, Brother of Jesus, which Moneo now has on his reading table, and I had also come across this predecessor of Marco Polo in Paul Zumthor’s Babel ou l’inachèvement, a luminous and evocative work the French medievalist and poet appropriately left unfinished on his death in 1995. The peruser of the Sephardic Jew traveler’s narrative of the Diaspora is distracted, his or her attention simultaneously drawn by Zumthor’s reflections about the building of the Babelic myth and about the problems our own Rafael de Tudela has had to face in his most daring work.

Moneo has suffered the first setback of his career precisely with his most experimental building. The collapse of the Kursaal’s auditorium staircase illustrates the vulnerability of contemporary technology.

The only two architectural pieces mentioned in the Bible are antithetical: the Temple of Solomon is of course a work of God; but the Tower of Babel is a construction of humankind, the confusion of tongues and the dispersion of its builders being the divine punishment for such an audacious violation of competences. The Apollonian temple and the Dionysian tower have survived in history as conflicting myths, and come down to our century in the opposition between the hermetic, material and gravid geometries that extend from Mies van der Rohe to Jacques Herzog on one hand, and the defiant, pictorial and ingravid forms that span from Le Corbusier to Rem Koolhaas on the other. The temple is subjected to divine law as well as to the laws of nature, whereas the tower rises up against them; in its gravity-defying attempt to reach the sky it challenged both God and physical laws, and Benjamín de Tudela the traveler offers a clear and accurate description of the marks left by such a futile endeavor: the ruins of ancient Babel and the ceramic remains of its spiral tower, a ziggurat now geographically identified by archeologists. To Zumthor, this unfinished tower is an emblem of the unfinishable nature of any human work, the beauty and risk of the enterprise, and the essential melancholy of its inevitable and foretold ruin.

In such a sacred, cosmic and entropic context, Rafael Moneo’s tribulations for the failure of a few weldings acquire a symbolical dimension: they represent penitence for his daring, poetic justice in chastisement of his defiance of gravity, and a warning to herald the ultimate destruction of all architecture. Beyond the irremediable attributions of responsibility in a collective project involving numerous professionals, beyond the unpredictable vulnerability of contemporary technique, and beyond the impossibility of ruling out the element of chance in a human venture, the small but large accident at the Kursaal is a reminder of the material and mortal condition of buildings and their authors. Yet perhaps the essence of art and life rests, precisely, in transgressing the laws that subject matter to gravity and bodies to dust; maybe freedom lies in lightness. And in any case, severe gravity will always defeat us: vehicles are inspected, but a bus can skid and run off a cliff; dams are guarded, but a dike may give and poison a river with mud; scaffoldings are checked, but «a bricklayer falls off a roof, dies and misses lunch,» as the poet César Vallejo summed up with apocopated ire. We rebel against chance, but chance vanquishes us: abutterfly’s wing provokes a storm, the horseshoe nail decides the result of a battle, and the fixing of a cable determines the stability of a construction.

In the territory of art, risk and beauty coexist. In Creueta del Coll Park in Barcelona, the sculptor Eduardo Chillida also saw one of his pieces fall to the ground, after the anchorage from which it was suspended gave way.

The Kursaal is a singular work, Moneo’s finest since the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, and it is so because in it he has taken tremendous risks. The matador has had afternoons of glory by making cautious passes, but in San Sebastián, the ring and professional pride have made him take on a bravado not ordinarily in keeping with his status as a consolidated figure, invoking instead his more juvenile, more lyrical and more ingravid project. Although esthetic risks must not be confused with physical ones, the jab Moneo has suffered halfway through the pass reminds many of us that we see the bulls from the barrier, with no fear of other wounds than errata, as the artist Kitaj bitterly complains in the pictorial repudiation of criticism now on display at Reina Sofía Art Center and Museum in Madrid; and this painful experience, which ultimately exalts the stature of the Navarrese architect, should also serve as a dark looking glass for complacent masters who have reduced their art to a grave routine. The nomadic shepherds of the book of Genesis were mistrustful of urban culture and the risks of technique; for them, the tower of Babel represented the foolish adventure of human autonomy, dangerous and impious in its defiance of heaven. In a commentary of the Biblical episode, the builders of Babel throw arrows upward from the top of the unfinished tower, and the arrows fall back down upon them, stained with blood. And perhaps this means that we cannot win over the heaven of art without wounding it and being wounded.

Esthetics of Risk

The experimental spirit of some of our finest architects, engineers and artists has been thrashed by a streak of bad luck that has turned esthetic risks into physical risks. Enric Miralles, whose unstable forms have always been more admired by his colleagues than by the public at large, took a severe beating five years ago when the roof of the Sport Hall of Huesca caved in, as a result of the failure of an anchor cable, but his stubborn energy managed to complete the building with another roof, also designed by him. Rafael Moneo, who had to put up with the incomprehension of many when faced with the avant-gardeness of Kursaal’s leaning and translucent prisms, now suffers a mishap in the execution of what is his most experimental building. And just a few days ago, on the 1st of May, engineer José Antonio Fernández Ordóñez and sculptor Eduardo Chillida – who as a team already were objects of an interminable public debate in the seventies when they proposed to hang the Beached Mermaid from Madrid’s Juan Bravo bridge, which was finally carried out – saw how a similar piece of reinforced concrete suspended over the Barcelona park of Creueta del Coll dropped to the ground, close to a group of visitors. Whether sculptural buildings or built sculptures, all these works explore the unmapped terrain that stretches between architecture and conventional sculpture, a wild territory where risk and beauty coexist.