The Madrid Plan Castro.

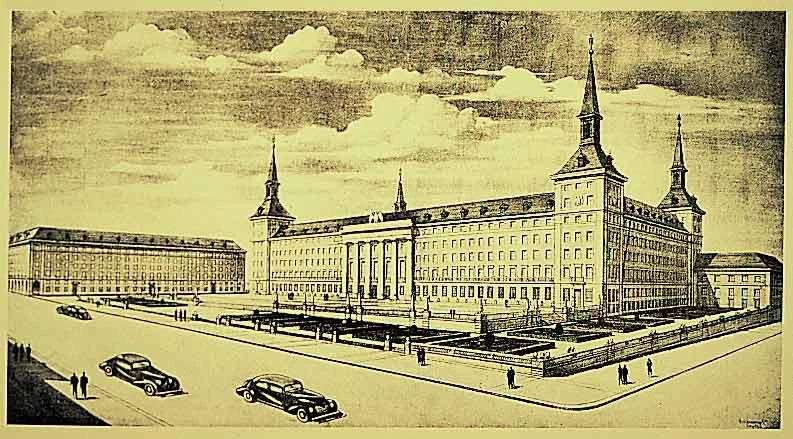

When Antoni Gaudí was born in 1852, less than ten years had passed since the founding in Madrid of Spain’s first School of Architecture, an outgrowth of the old Academy of Fine Arts. The vigorous urban development of the Restoration called for a new generation of trained builders, and the young Gaudí, who first studied in Barcelona’s Science Faculty, could complete his education in this city’s own architecture school, established just a few years before his graduation. The new architects of Madrid and Barcelona were to launch their careers in the midst of the urban growth fostered by the Ensanche laws of 1864, 1876 and 1892. Barcelona with its Plan Cerdá of 1859 and Madrid with its Plan Castro of 1850 set the pattern for the rest of the country, and which in the Catalan case benefited from the strategic talent of Ildefonso Cerdá, whose Teoría General de la Urbanización established the base of modern urbanism. Enriched by mining, railways, Basque iron works and the Catalan textile industry, the bourgeoisie undertook urban development with an energy also nurtured by foreign investments and stock market dynamism.

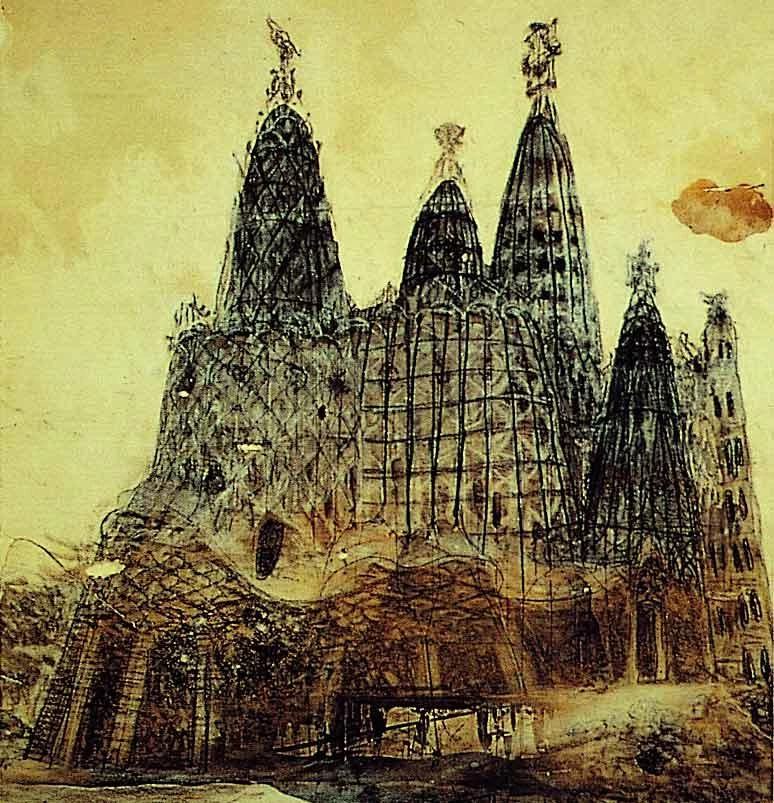

The historical conscience instilled by the architecture schools, the boom of monument restoration and reconstruction, and the late-Romantic climate that impregnated the final third of the century all fueled the adoption of eclectic historicist languages, especially neo-medieval ones. Both the influence of Viollet-le-Duc and the building vigor of bourgeois Catholicism, spurred on by the Vatican Council I (1869-1870), produced a neo-Gothic revival that crystallized in a large number of religious buildings, some of such scale and ambition that they took ages to complete. This was the case of Madrid’s Almudena Cathedral, the construction of which was initiated in 1880 following a Gothic project, and terminated a century later in neoclassical style, or of Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia, which began to go up in 1881 on a medieval scheme, only to be entrusted not long after to Gaudí, who would never see the end of it – despite unrelenting dedication until his death in 1926. The latter part of the 19th century was also witness to the massive introduction of iron architecture, which was first used for stations, markets and bridges but soon permeated other types of constructions, and which was immediately judged to be the best expression of technical progress and the positivist ideals of an enterprising bourgeoisie.

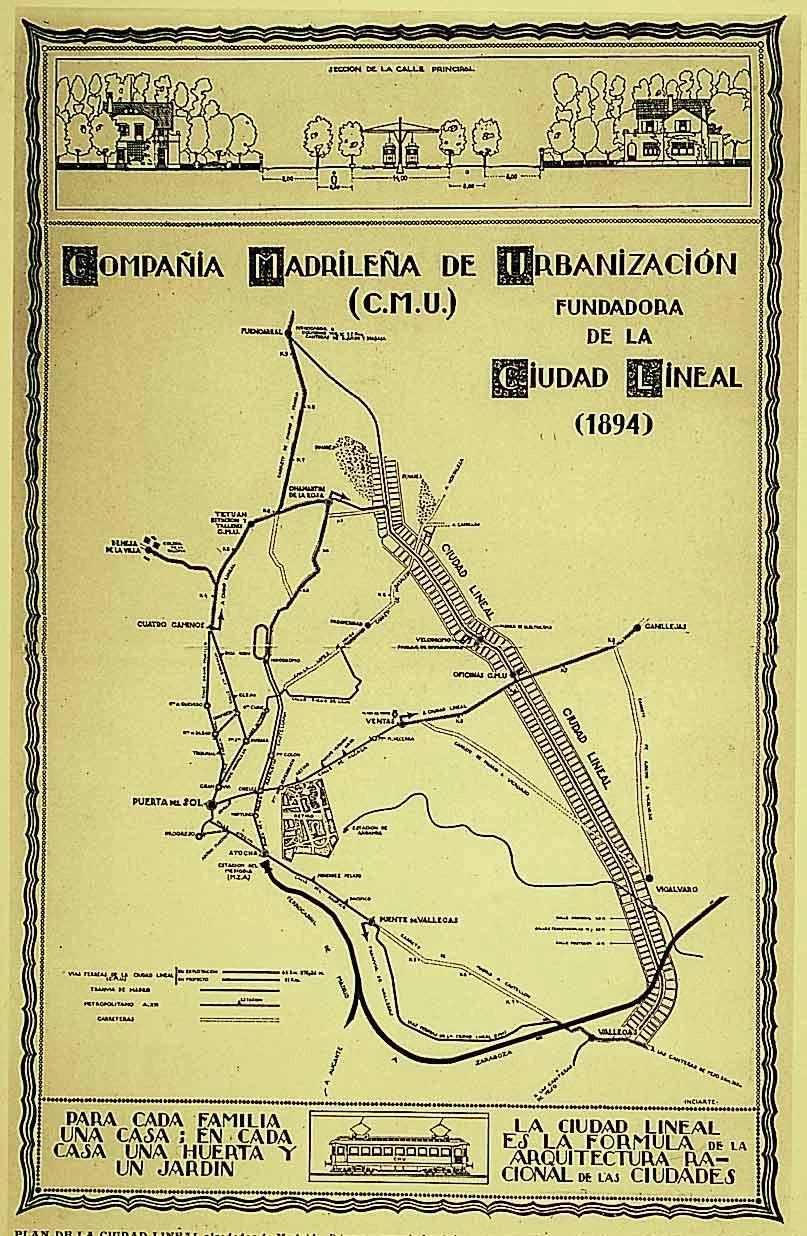

The Madrid Plan Castro (above) and the Barcelona Plan Cerdá (below) control urban development in the final third of the 19th century.

Barcelona Plan Cerdá.

In Catalonia, this bourgeoisie expressed its impetus through modernismo, a style of a curvilinear abstraction whose most brilliant interpreter was Antoni Gaudí, and whose most representative architect was Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Gaudí’s almost exact contemporary. Domènech began his career in the usual neo-medievalism of romantic nationalism, which exalted the glories of Catalonia’s medieval past, and admirably fused it with Industrial Revolution iron in the Café-Restaurant he built for Barcelona’s 1888 World’s Fair. But from here on his work would be modernista, and it was this florally rationalist language, influenced by European Art Nouveau, that he used in his most important building, the Palau de la Música Catalana in Barcelona (1905-1908), a polyphonic architecture that fuses industrial arts and crafts to compose a polychromatic Wagnerian piece. Younger architects like the historicist Josep Puig i Cadalfach or Gaudí’s disciple Josep Maria Jujol would prolong modernismo well into the 20th century, but its optimistic forms would not survive the crisis of traditional society in the twenties.

Ciudad Lineal of Madrid, by Arturo Soria.

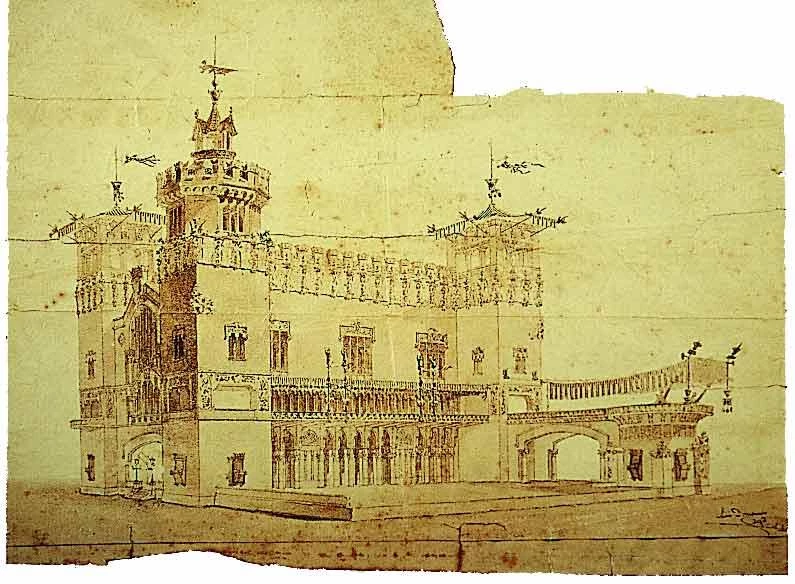

Café-Restaurant by Domènech i Montaner in the Exhibition of 1888.

The greatest modernista, though a hardly classifiable figure, was Gaudí, whose structural and naturalist expressionism merged severe constructive rationalism with exotic formal fantasies. From the bottle-shaped steeples of the Sagrada Familia –which evoke Berber constructions as much as the pointed rocks of Montserrat, a sacred place to Catalans – to the parabolic arches he used so profusely in his belief that the esthetic logic of this curve was proof of the divine origin of natural laws, his work amalgamates structural intelligence with an almost pantheistic religiosity. Whether in Parc Güell or in the crypt of the chapel of Colonia Güell (both built between 1898 and 1905 under the auspices of his great Maecenas, Eusebi Güell), or in Casa Milà (1906-1910), his constructive genius, naturalist sensibility and sculptural expressivity produced rare and disturbing shapes bordering on surrealism.

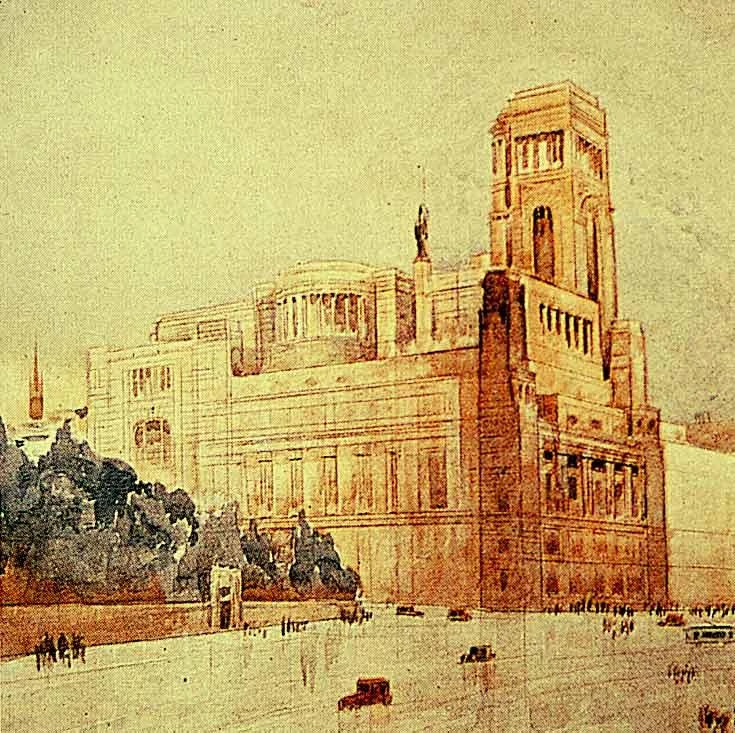

Elsewhere in Spain, the early decades of the century witnessed the coexistence of traditional academic monumentalism –represented by architects like Antonio Palacios, the author of some of Madrid’s most emblematic buildings, from the main post office (1903-1918) to the Círculo de Bellas Artes (1919-1926) – and the renovative ferment of regionalisms, which took inspiration from local architectures in order to defend their roots and identities. Nevertheless, both the montañés style of Leonardo Rucabado and the Sevillian style of Aníbal González shared the historicist approach of Palacios’ monumentalism, an attitude which on hindsight is hard to distinguish from eclecticism. When Mies van der Rohe built his pavilion at Barcelona’s 1929 fair, its radical novelty exposed the limitations of the Spanish scene, where young architects were only concerned with whether to design in Renaissance style, as the schools had taught them, or in Cubist style, as the most daring of them did.

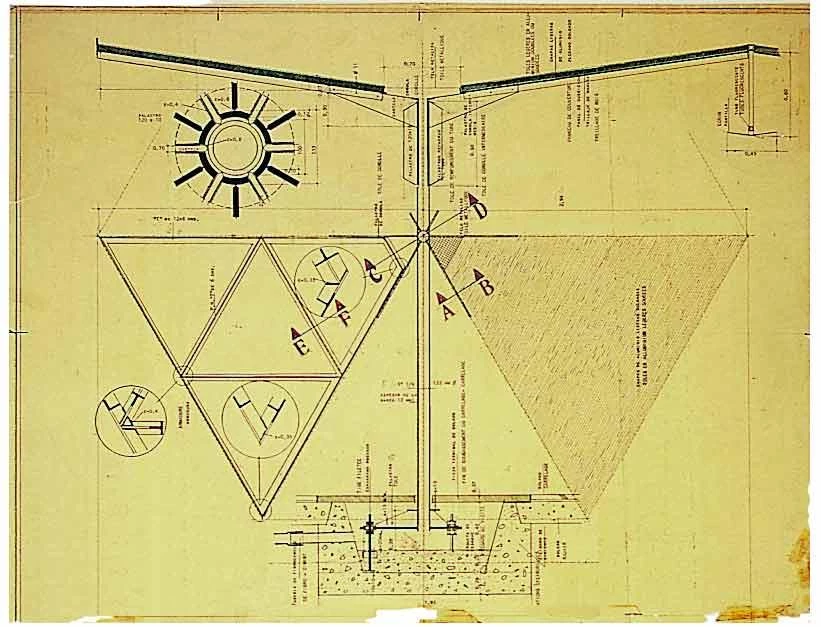

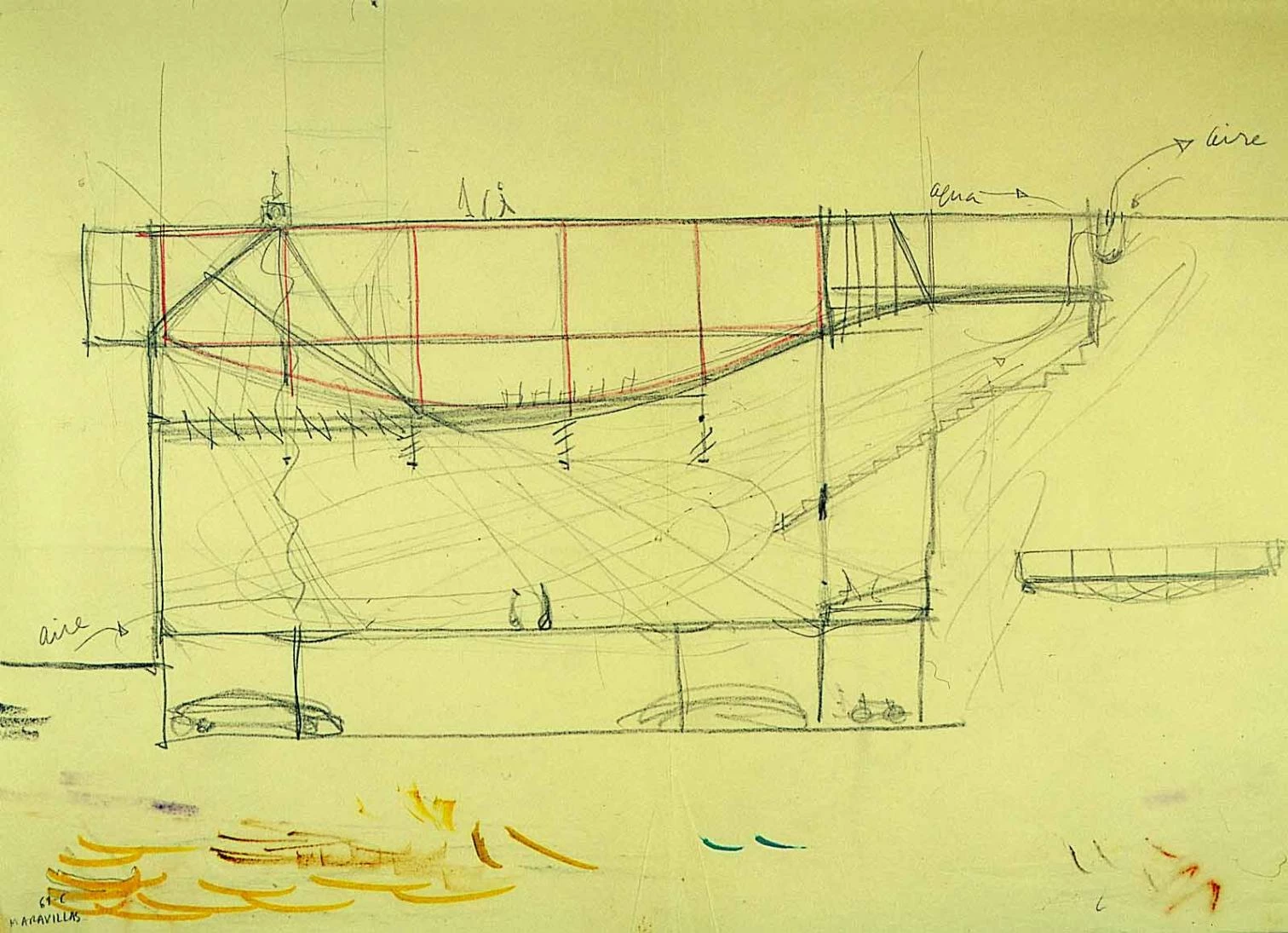

Gaudí’s project for the chapel of Colonia Güell.

Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, by Antonio Palacios.

In fact the most original and radical proposal of the period was Arturo Soria’s Ciudad Lineal, which hardly drew attention at the time. Formulated in 1892 and carried out in Madrid as a linear garden-city organized along a longitudinal public transport axis, the adventure continued into the 1920s without arousing the interest and support it deserved. Public urban planning efforts went instead to the 1929 fairs of Seville and Barcelona, and to Madrid’s Ciudad Universitaria, which was drawn up in 1927 on the model of the American campus but built during the Republican period, 1931-1936, in the sober brick rationalism that characterized the young architects known as the ‘generation of 1925’. Master to them all was the severe Secundino Zuazo, the eclectic architect and rational urbanist who did the Casa de las Flores in Madrid (1930-1932), an excellent example of urban housing, and with Eduardo Torroja, the Frontón Recoletos (1935), whose roof of spectacular shells of reinforced concrete would also be used by the engineer for the elegant stands of the Zarzuela racetrack –completed, like the Ciudad Universitaria, shortly before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in the summer of 1936.

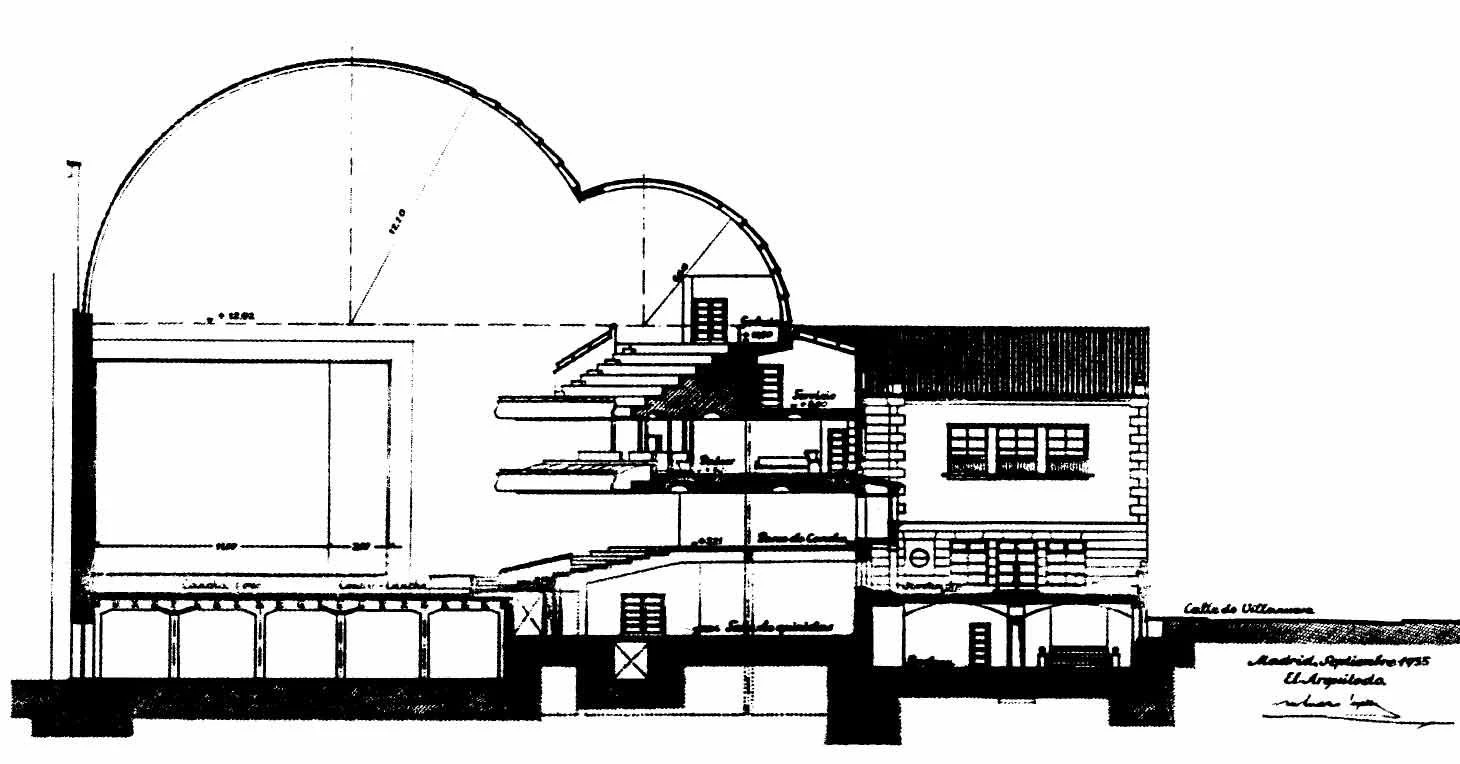

Frontón Recoletos, de Zuazo con Torroja.

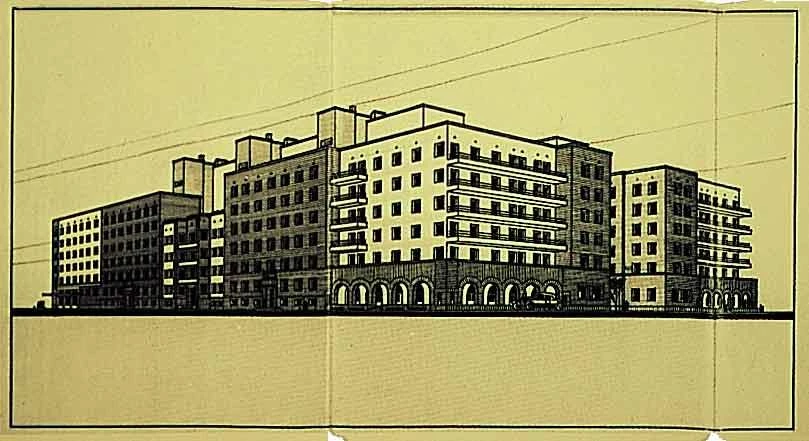

Casa de las Flores de Zuazo.

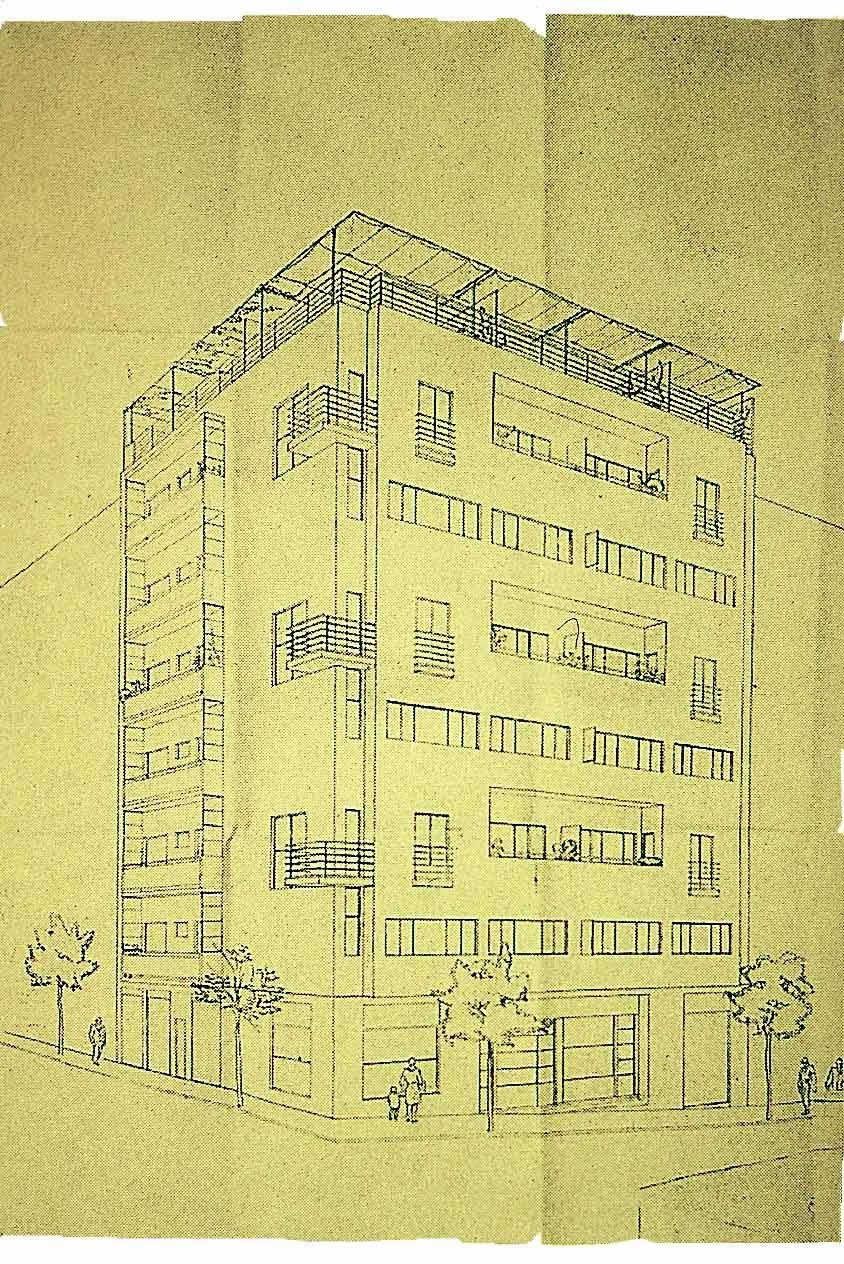

The Frontón Recoletos, by Zuazo with Torroja, the Casa de las Flores also by Zuazo, and the building on Muntaner Street, by Sert, all significant works of the rationalist movement halted by the Civil War.

The war destroyed a good part of the campus – battlefield of the protracted siege of Madrid – and put a halt to the rationalist renewal of architecture, in both its moderate Madrid form and the more orthodox, radical and white version developed in Barcelona, the main nucleus of the GATEPAC – a group of Le Corbusier followers headed by the small and tireless Josep Lluís Sert. During the republican years this leftist aristocrat and his colleagues built the worker’s homes of Casa Bloc (1932-1936) and the Tuberculosis Sanatorium (1934-1936), two exemplary projects of the hygienist rationalism that the members of the group had also theorized on in urbanistic proposals such as the 1933 Plà Macià for Barcelona, drawn up with Le Corbusier himself. With the war underway, Sert designed the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, a propaganda effort of the threatened Republic (for which Picasso painted his celebrated Guernica, a black and white condemnation of war) which failed to alter the course of events. These finally ended with the defeat of the Republic in 1939 and the dissolution of the architectural avant-garde, some of whose constituents had died in the conflict. Others went into exile, such as Sert himself, who would undertake the rest of his career in the United States, replacing Gropius as the dean of Harvard.

The building on Muntaner Street, by Sert.

Syndicates building in Madrid, by Cabrero.

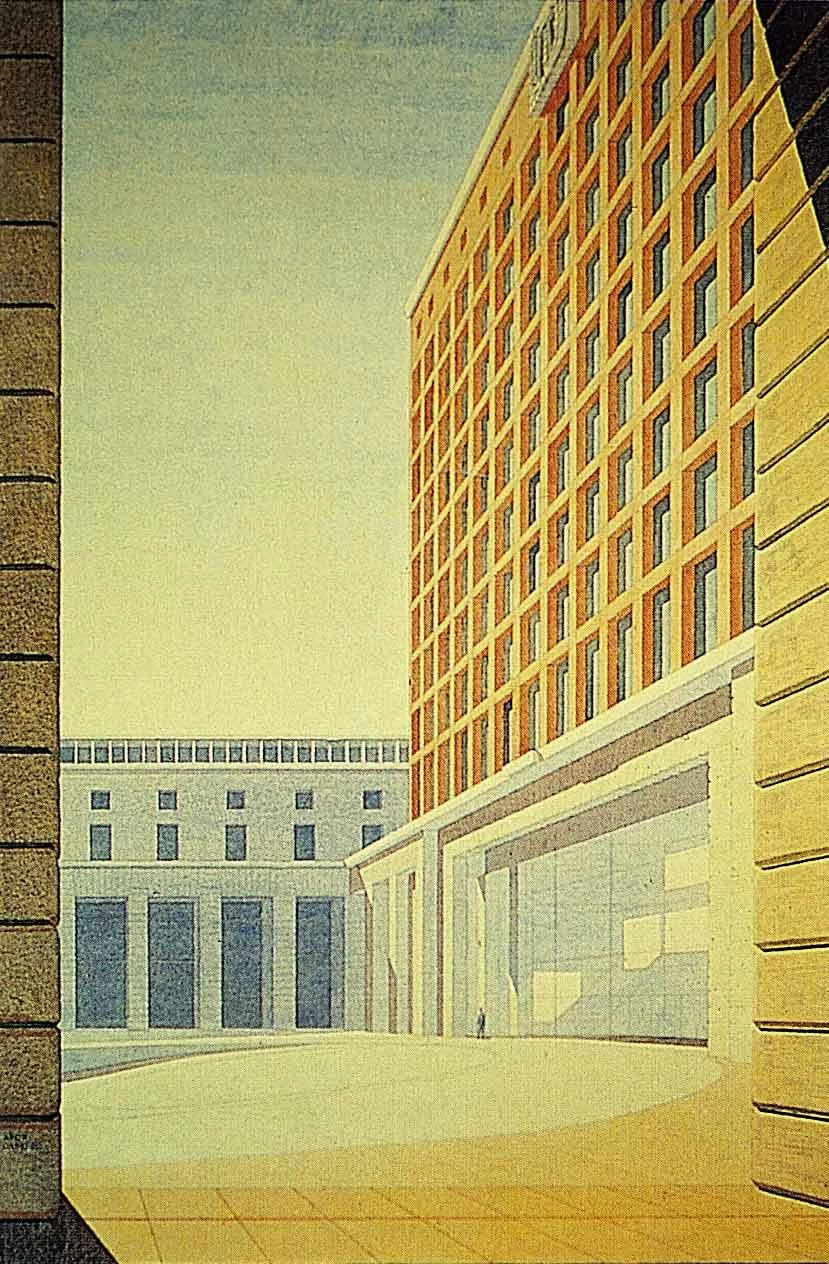

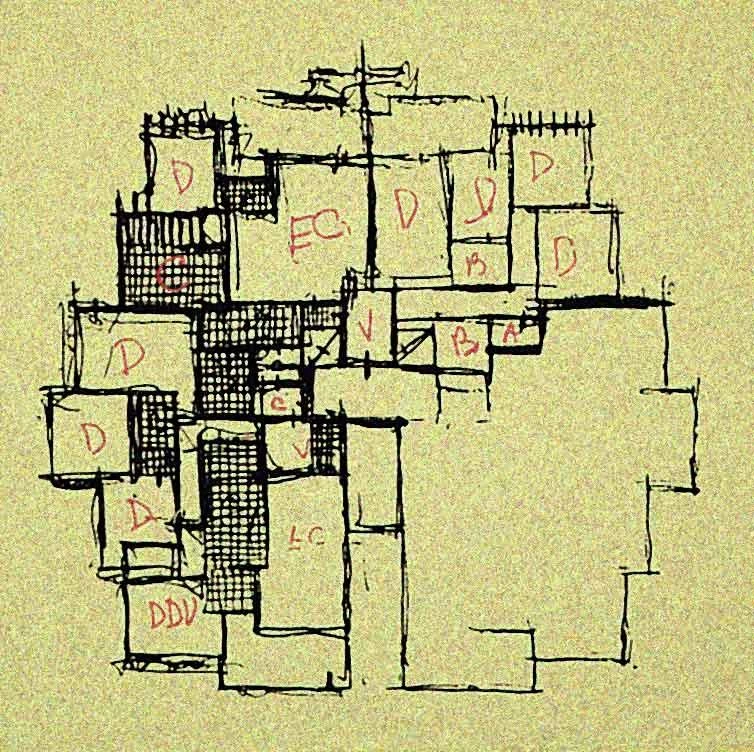

After the war, classicist monumentalism was the preferred style for public architecture. The Ministry of the Air, by Gutiérrez Soto and the Syndicates building by Cabrero, both works in Madrid

Postwar reconstruction favored a national classicist monumentalism for large public buildings and a neo-vernacular vocabulary for rural areas. Architecture of power had to evoke the language of the Spanish Empire (which Franco considered himself a continuer of), admirably represented by the huge stone mass of the monastery of El Escorial that Juan de Herrera built for Philip II, while popular architecture was to find inspiration in local traditions. Thus architects who had been modern before the war, such as the gifted and versatile Luis Gutiérrez Soto, now worked in the neo-Herrerian style so perfectly exemplified by his Ministry of the Air (1942-1951), a heavy building contradictorily meant to house the newly-formed Air Force. Others, like Luis Moya, obtained public backing to erect complexes of megalomaniac dimensions, such as Moya’s own Universidad Laboral de Gijón (1945-195), a classicist citadel that constituted the polemic reverse of Madrid’s devastated modern campus. And others still, including the rigorous Francisco Cabrero, interpreted the official monumentalism in terms of Mussolinian rationalism, as in his Syndicates building of Madrid (1949), the disciplined sobriety of which would lead him in the next decade toward Mies van der Rohe’s constructive abstraction.

Ministry of the Air in Madrid, by Gutiérrez Soto.

Spanish Pavilion at the World Fair in Brussels by Corrales and Molezún.

The fifties saw the return of the Modern language, enriched by vernacular tradition or, as in the Spanish Pavilion at the World Fair in Brussels by Corrales and Molezún, by technical experimentation.

Indeed the fifties saw a return to modern language, a process facilitated by the growing pragmatism of the political regime and the end of international isolation; but a modern language, to be sure, that had by now abandoned the functionalist fundamentalism of the avant-garde, and which professed an interest in the climatic, topographical and constructional peculiarities of each place. In both Madrid and Barcelona, architects used the wise rationalism of vernacular forms to reinterpret tradition in abstract terms, an approach that was especially appropriate to domestic projects: as in the case of the villages for rural settlers by Madrid’s José Luis Fernández del Amo, or the houses for Barcelona’s bourgeoisie by the Catalan José Antonio Coderch. At the end of the decade, the youngest and most radical architects, that included Oriol Bohigas in Barcelona and Antonio Vázquez de Castro in Madrid, had the opportunity to try out empirical rationalism in social housing developments promoted by the State to absorb, on the outskirts of large cities, the growing rural migration caused by the modernizing of economic and social structures.

Public buildings, in turn, expressed the renewal through technical and formal experimentation. The leaders here were José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún, authors of the Spanish Pavilion at the 1958 World Fair in Brussels, a mechanistic construction of hexagonal metal unbrellas which became an emblem of change; Miguel Fisac, builder of numerous research centers with bones of prestressed concrete; and Alejandro de la Sota, who left two masterworks, of rationalist abstraction in the Civil Government Delegation of Tarragona (1957-1964) and of technological neo-realism in the Maravillas School Gymnasium in Madrid (1960-1962). The economic development of the sixties and the building boom that accompanied it – and that caused so much damage in historical quarters and coastal landscapes – found expression in the organicist formalism of young professionals like Fernando Higueras, whose houses in Madrid’s sierra for well-to-do progressive intellectuals and artists, members of the expanding middle classes, show the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright; or like Antonio Fernández Alba, whose convents in Salamanca for a Catholic Church steeped in a process of renewal, accentuated in the wake of Vatical Council II (1962-1965), manifest an admiration for Alvar Aalto. But the most characteristic building of this period would come from a mature architect, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, whose sculptural Torres Blancas (1960-1968), a residential concrete skyscraper that greets one entering Madrid from the airport, constituted the most eloquent representation of the decade’s optimistic prosperity.

Las Cocheras housing, by Coderch.

Torres Blancas, by Oíza.

During the sixties, dynamic economic development found its plastic expression in organic formalism. Las Cocheras housing by Coderch and Torres Blancas by Oíza.

In contrast, the seventies were to see the confluence of several crises: the economic crisis induced by two successive oil shocks; the political crisis resulting from the social conflicts of Franco’s last years and the tense uncertainty that followed the dictator’s death in 1975; and the ideological crisis sparked by the youth rebellion of 1968, which in architecture harmonized with the revisions of modern postulates that Aldo Rossi and Robert Venturi propounded in their books of 1966. The young architects expressed their breakaway from the bureaucratic modernity of so many of their elders through a radical, anti-modern and post-modern classicism that they often summed up in small building-manifestos. Thus the ironic, sensual and Mediterranean classicism of the Catalans (Ricardo Bofill, Lluís Clotet, Oscar Tusquets), the fundamentalist classicism of the Basques (José Ignacio Linazasoro, Manuel Íñiguez, Alberto Ustarroz) and the anthropological, ethnographic classicism of the Galicians (César Portela, Manuel Gallego) all highlighted the vitality of regional cultures, immersed in a process of asserting the identity of the peripheries, to which the reestablishment of democracy would give free rein in forming institutions for self-government; a process accentuated by the creation there of new architectural schools and associations.

Bankinter headquarters, by Rafael Moneo.

Between the technological neo-realism of Sota’s Maravillas Gymnasium, and the contextual historicism of Moneo’s Bankinter architecture experienced the crisis of orthodox Modernism of the 70s.

But the most influential classicism would be the moderate, cultivated and contextualist version of Rafael Moneo, a Navarrese based in Madrid – while a teacher in Barcelona –who gave the capital’s Castellana the Bankinter headquarters (1972-1977), a refined, discreet building which combined a respect for urban memory with a silent affirmation of modern abstraction. Such intellectual civic virtues were to find their most forceful and eloquent expression in the Museum of Roman Art of Mérida (1980-1986), a severe, scenographic masterpiece whose solemn arches over an archaeological site put Moneo in the international limelight while becoming an emblem of Spain’s new architecture, by then the object of wide popularity and diffusion in the world. For Spanish architecture, true enough, the eighties were a period of effervescence, motivated by the economic euphoria of the second half of the decade, the generous patronage of public administration – in socialist hands since 1982 – and the heyday of exhibitions and specialized journals, which would air the numerous built works outside peninsular frontiers.

The lyrical, self-satisfied architecture of these years was enriched by the emergence of professionals endowed with a personal language: the Santander – born and Madrid – based Juan Navarro Baldeweg, a celebrated painter and the architect of the weightless dome crowning Salamanca’s Convention Center; the Catalan Enric Miralles, who in collaboration with Carme Pinós built the inspired, poetic and surreal cemetery-park of Igualada; the Andalusians Antonio Cruz and Antonio Ortiz, creators of the sober and luminous station of Santa Justa in Seville; or the Valencian Santiago Calatrava, a sculptor, engineer and architect who, from his Zürich and Paris studios, built several powerfully sculptural bridges in Spain.

Maravillas Gymnasium, by Alejandro de la Sota.

Such flowering of artistic talent reached full swing in 1992, the year the Olympic Games of Barcelona coincided with an Expo commemorating the fifth centenary of the discovery of America, held in Seville. Both events drew a huge share of social and cultural energies, and sealed Spain’s internationalization, all the stronger in architecture for the import of foreign professionals, among which the Japanese Arata Isozaki, author of the rotund Palau Sant Jordi in Barcelona; the American Richard Meier, who built the neo-corbusian Museum of Contemporary Art in the same city; the Portuguese Álvaro Siza, author of the refined Galician Center of Contemporary Art in Santiago; and the British Norman Foster, who built with his characteristic technical elegance Barcelona’s Collserola Tower and Bilbao’s underground.

But 1992 also saw the end of euphoria, with the difficulties of European integration, the rise in unemployment and several corruption scandals. Madrid’s leaning KIO towers, two awkward skyscrapers designed by the American Philip Johnson, would be the best symbol of this period of uncertainty; and the Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao, a magnificently sculptural stormy shape clad in titanium, built by another American architect, Frank Gehry, the most sparkling image of Spain’s incorporation into the new cosmopolitan society of spectacle.