Franco never died; he decomposed. His agony, just like his regime’s, was so longand so slow that the eventual news of his demise was received with a serenity bordering on indifference. Twenty-five at the time, I was living the lawful life of an architect and another, clandestine existence as a political activist. Two years before ETA had murdered the general’s dauphin, Admiral Carrero Blanco, and fear of a “night of long knives” had sent me sleeping away from home, as it did the majority of us involved with illegal parties – few and in most cases well known to the police. But Franco’s death did not alter my habits and the evening of November 20, 1975 found me in my own bed, neither anxious nor euphoric.

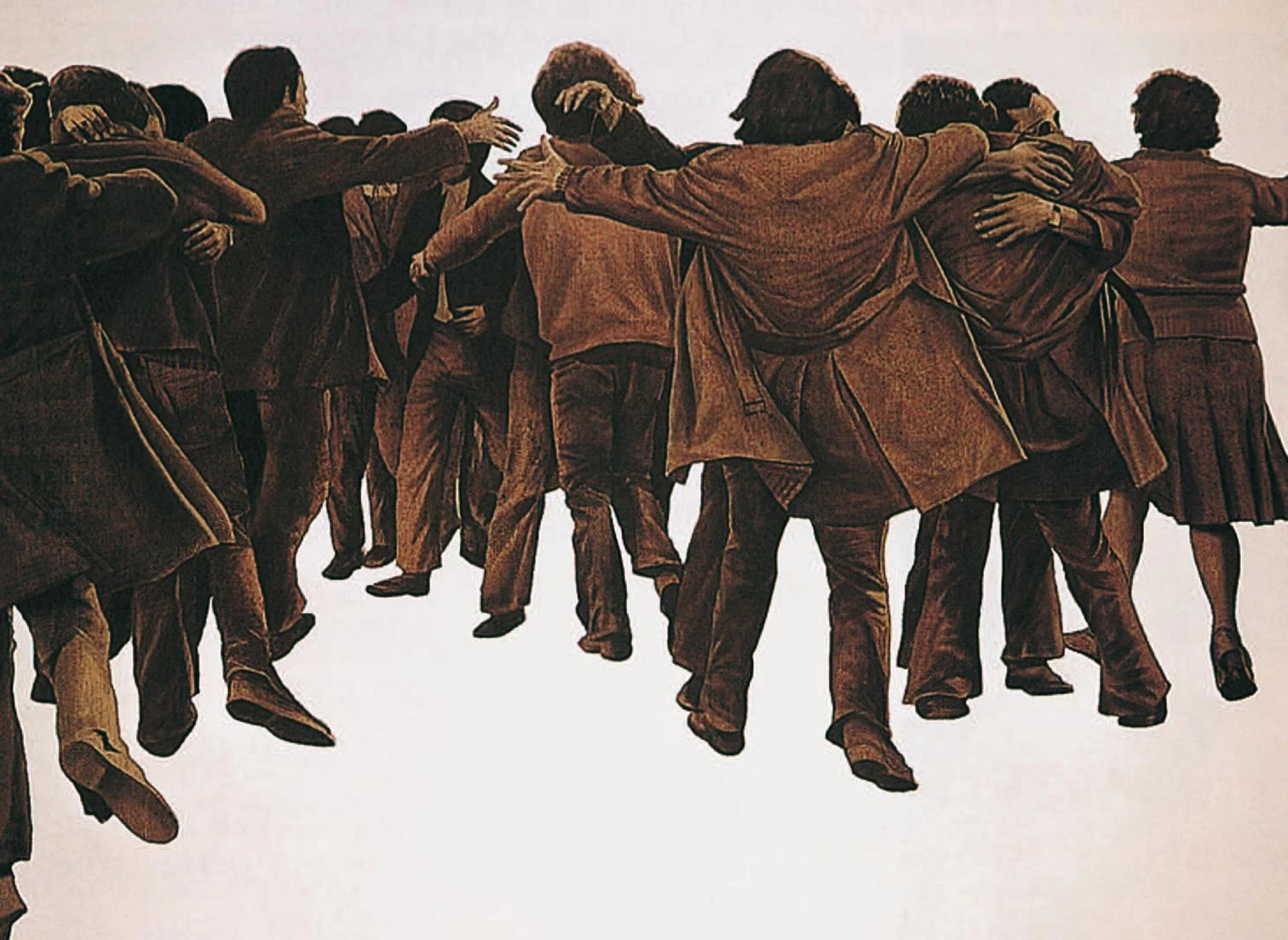

El abrazo, Juan Genovés, 1976

In those years there were still two Germanies, but also two Spains: two countries separated not by a physical frontier, but by an emotional barrier hoisted in every city and every family. In the months that followed, the street was the scene of those divergent sentiments. From the massive mourning of the dictator tothe demonstrations clamoring for freedom, each Spain appraised its strength with more precaution than drama, avoiding a confrontation exorcized by the ghosts of the Civil War. The result we well know, a mutual amnesty that took the form of amnesia, and allowed the painless birth of a normal country. Many had predicted or dreaded a bloody delivery, but instead we experienced a metamorphosis; between Francoist larva and democratic butterfly, pupa Spain had its day with no further violence than the breaking of the cocoon sewn with the thread of old laws.

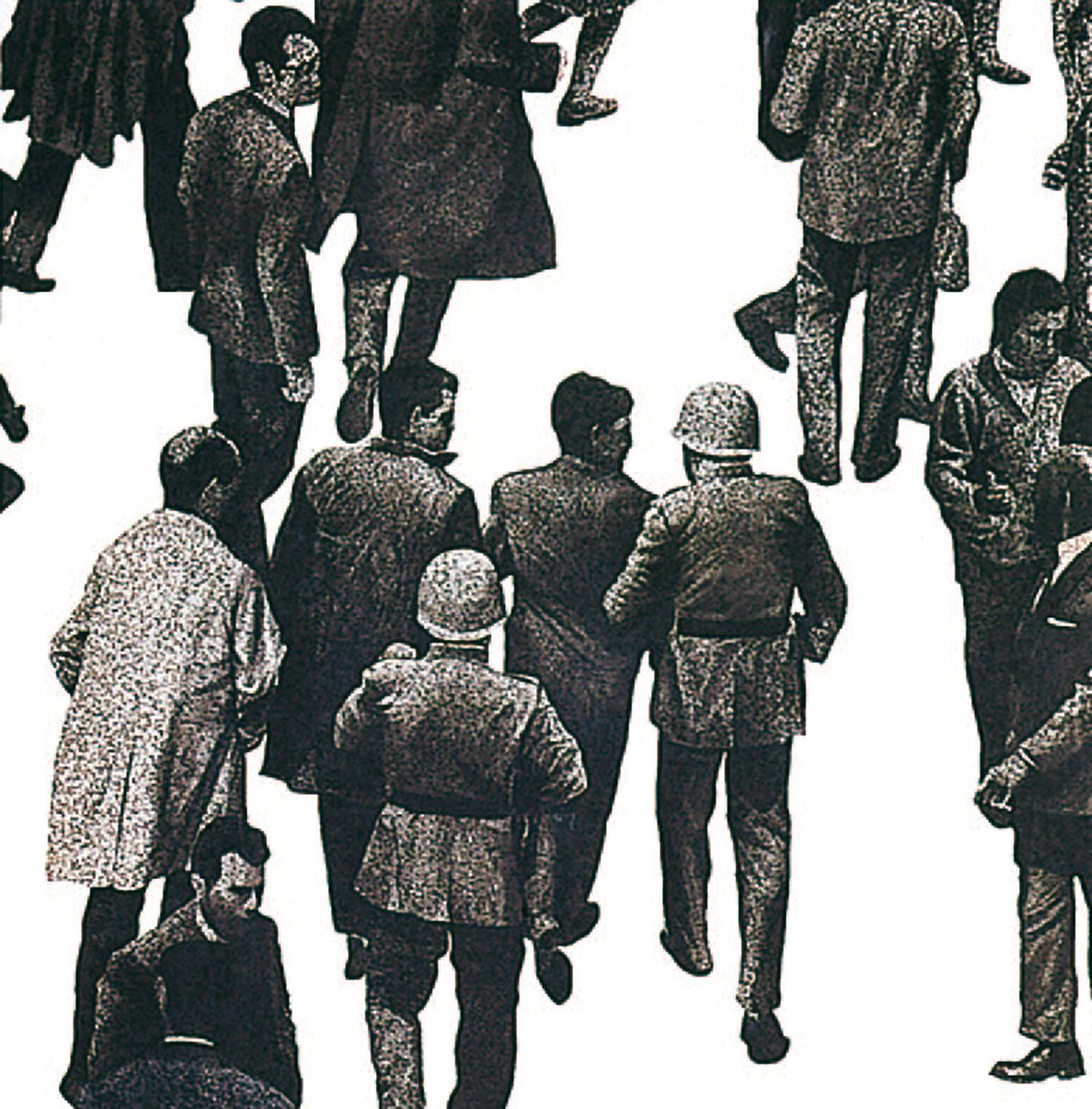

The Spanish transition to democracy is portrayed in two works of Juan Genovés: En la calle, 1975 and El abrazo, 1976 (above); and Juan Muñoz’s Instalación de los chinos (below) represented in 1995 a new egalitarian feeling.

Instalación de los chinos, Juan Muñoz, 1995

Nevertheless it was not an easy period for anyone, and neither for architects. The economic crisis induced by the soaring of oil prices in 1974 had paralyzed many projects, and the second energy convulsion in 1979 brought about a standstill that would last into the eighties. With some friends, I started to practice the profession under the highflown name ‘Collective of Architecture’, and suffered the gale of accelerated history: our most innovative work, a solar house that expressed the moment’s fascination with ecological buildings and alternative energy sources, ended up heated by fuel-oil; and our most important commission, a large tourist hotel on the desolate dunes of El Aiun, capital of the Spanish Sahara, was canceled after the Green March of 1975, the audacious movement of Hassan II which, in the uncertain days of Franco’s physical decline, allowed the Moroccan king to annex Spain’s last African colony.

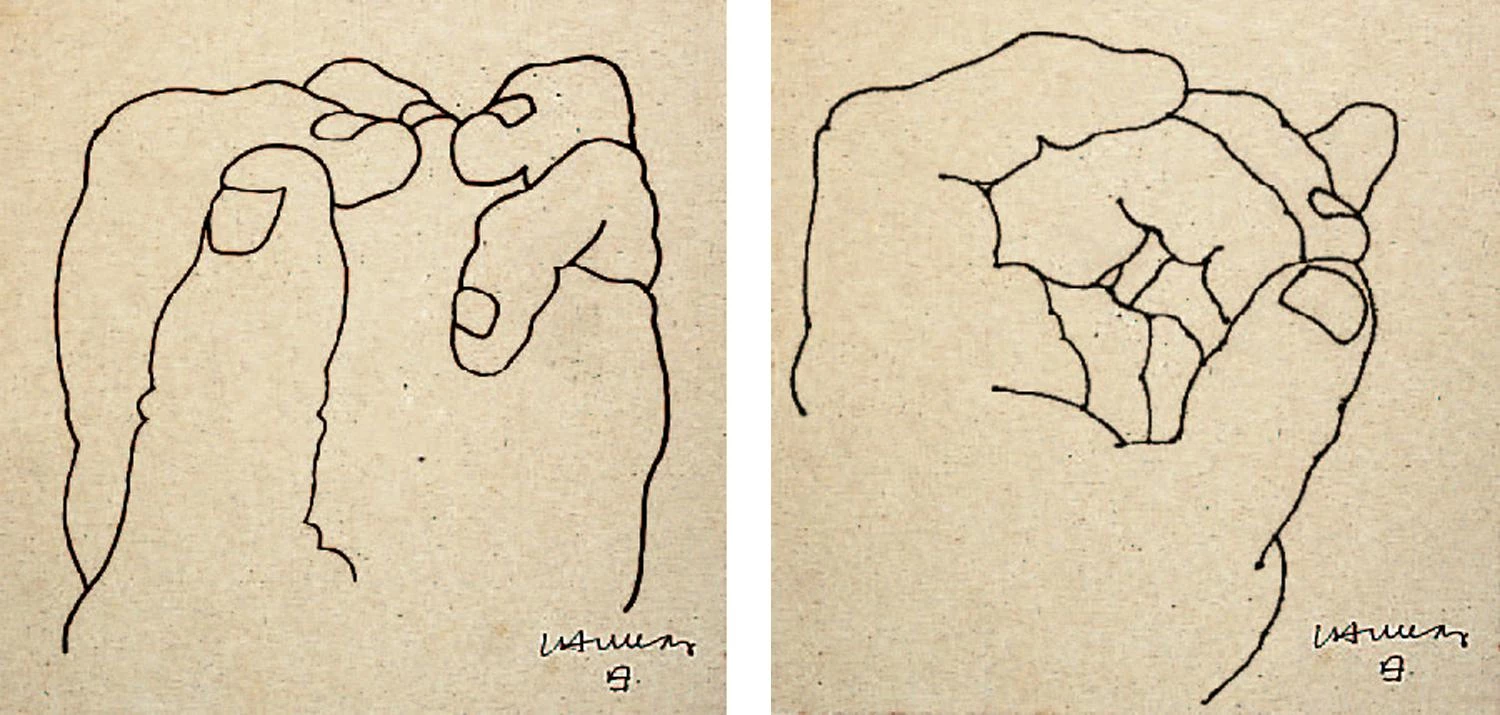

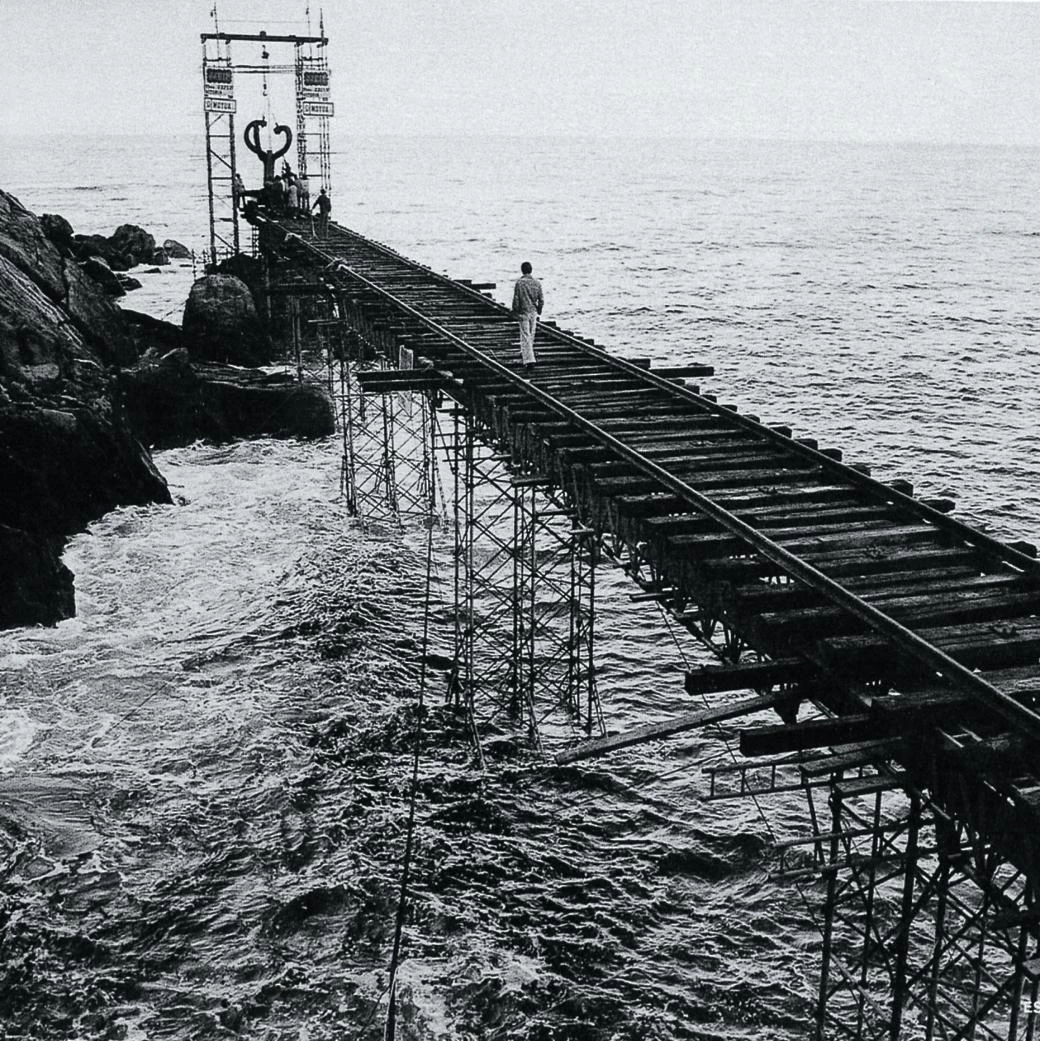

The work of the Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida (on the right, the set up in San Sebastián in 1977 of El Peine de los Vientos) was the emblem of the struggle for freedom, as it is today of the struggle against terrorism.

The set up in San Sebastián in 1977 of El Peine de los Vientos, Eduardo Chillida

The architectural associations, then arena of a political clash soon to extend to the new democratic institutions, also served as channel for a transformation of the profession that would turn urban reformers into protectors of heritage, esthetic avantgardists into artistic populists, and modern Utopians into cautious postmoderns. When Franco died, Madrid’s architectural association – I was on its executive board – was a platform of unrest and propaganda for clandestine political parties, which used social conflicts and urbanistic corruption as publicity weapons against the dictatorship. Rejecting the narcissism of ‘signature architecture’ was in tune with the silent anonymity that the architecture schools were preaching, and with the traditionalist respect for heritage that was being clamored for by a society scandalized by the devastation of historic centers and coasts during the economic boom of the sixties. So it was that leftist dissidents became, paradoxically, the protagonists of a conservative architectural reaction.

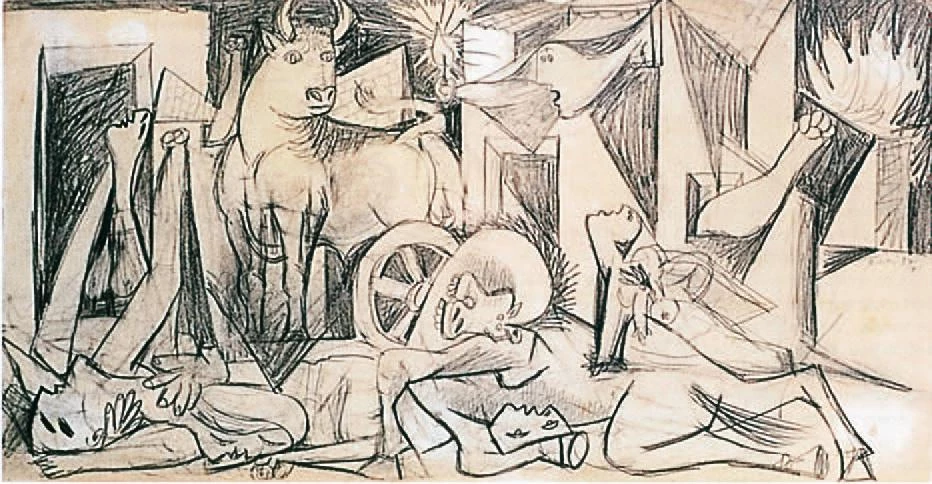

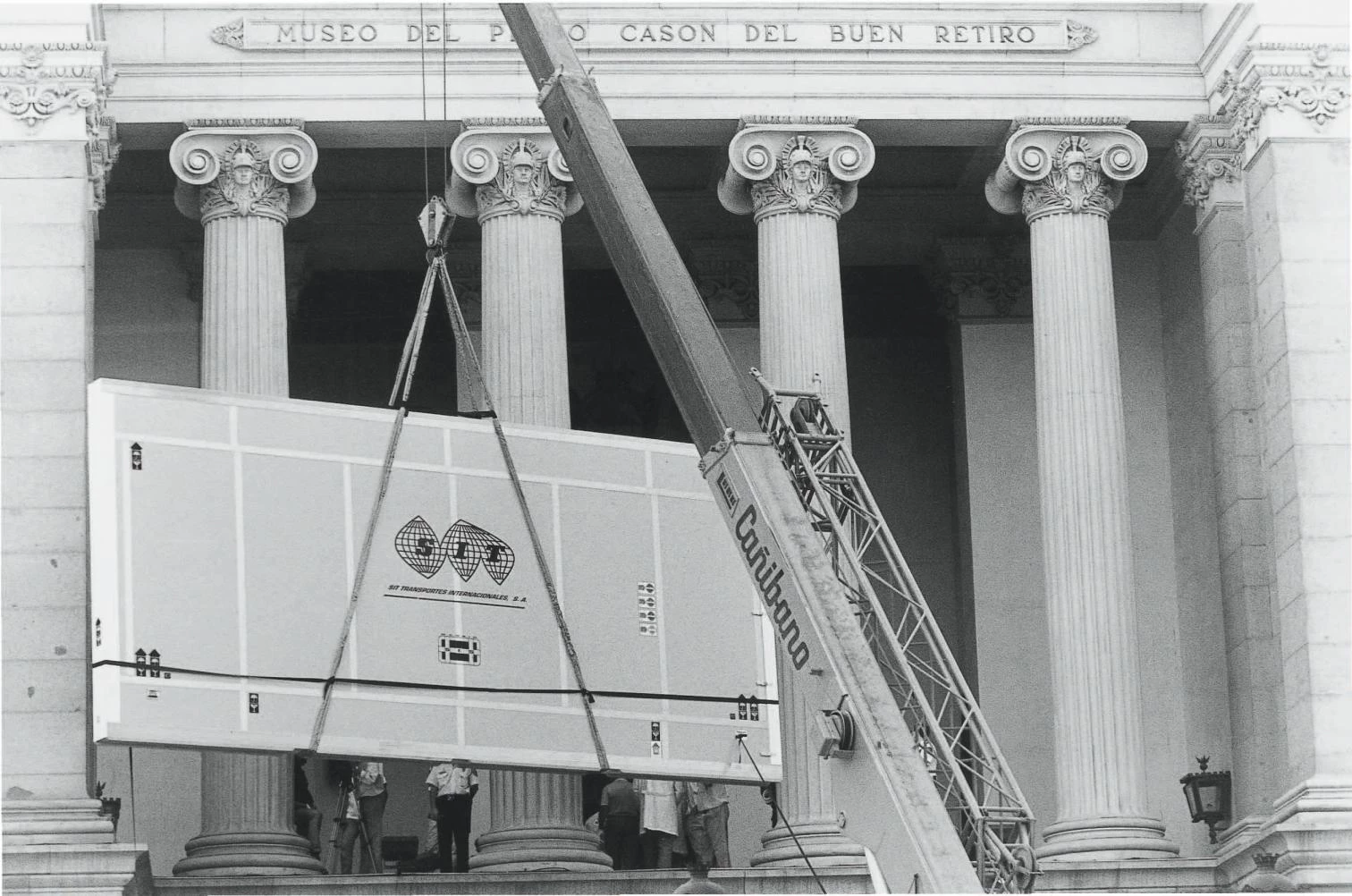

Democratic normalization brought back those in exile and Picasso’s Guernica, but also the dominion of economics over politics, commerce over culture, and habit over exception, creating a disappointment that some expressed as “against Franco we were better off.” The society of spectacle put the limelight on Spain in 1992, and the country adorned the architectural fruits of its prosperity with the reconstruction, in facsimile, of two mythical pavilions by exiled authors: the German Pavilion of Barcelona 1929, the work of a Mies van der Rohe who with the rise of the Nazis was to leave Berlin for Chicago; and the Spanish Pavilion of Paris, showcase of the Guernica, the creation of two architects destined to abandon Spain in the wake of Franco’s victory in the Civil War: José Luis Sert, who settled in the United States, and Luis Lacasa, who escaped first to the Soviet Union and then to China. From the Barcelona of the Olympic Games to the Bilbao of the Guggenheim Museum, the Spain that was a chrysalis twenty-five years ago is now a light and mediatic butterfly where the only grave conflict is that brought on by an ethnic nationalism of a kind more dangerous for Europe than Haider’s, where Chillida sculptures previously symbolizing the fight for freedom are now emblems of the fight against terror, and where the only exiles are those who are fleeing from a Basque Country now reduced to being the last redoubt of Spain’s tragic history: a history that began to fade with Franco’s extinction a quarter-century ago.

And the return to Spain of Picasso’s Guernica (its move from the Casón del Buen Retiro to the Reina Sofía Museum) symbolized the homecoming of exiles after the restoration of democracy in the country.