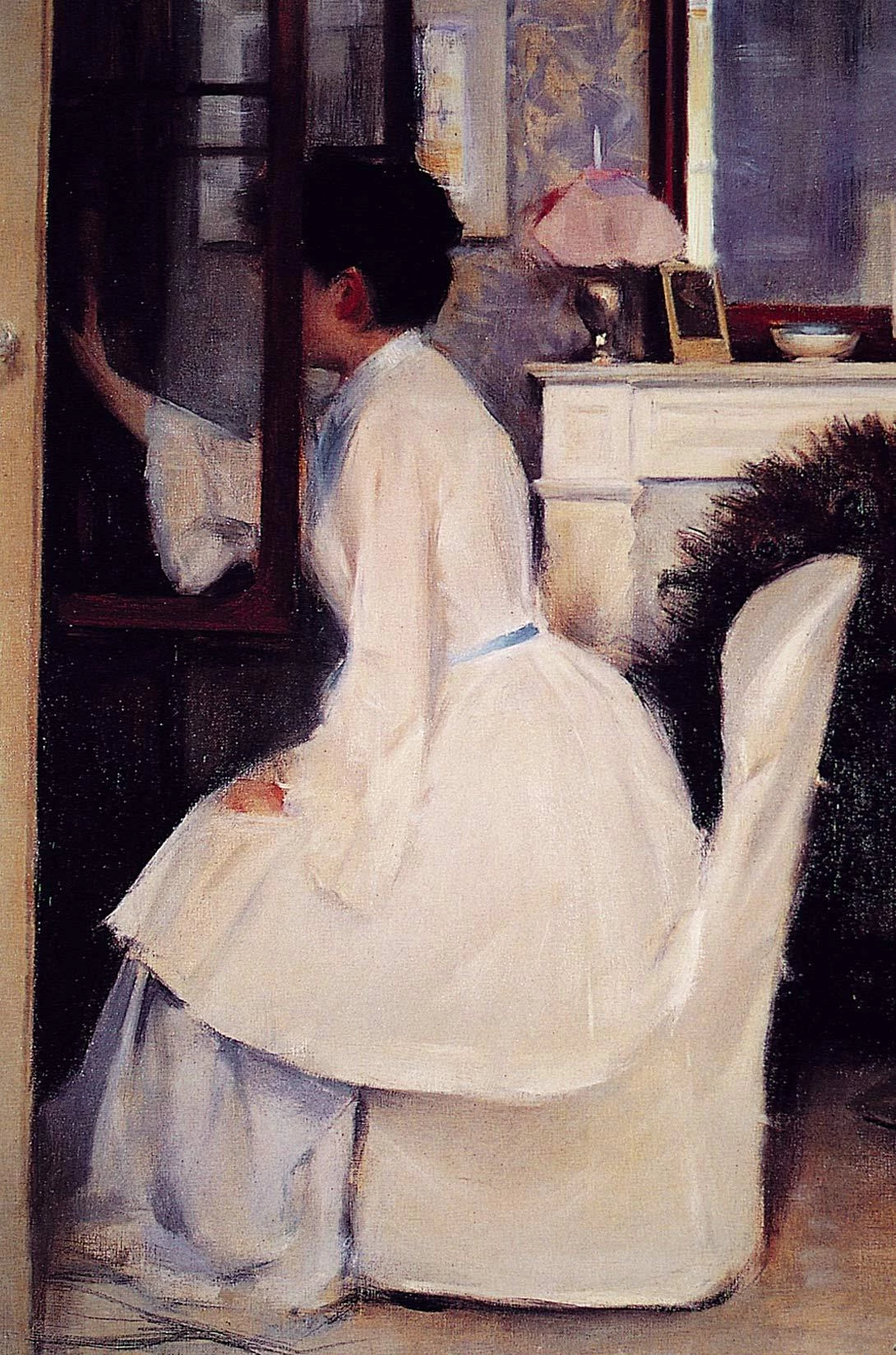

Interior (c. 1890), by Ramón Casas.

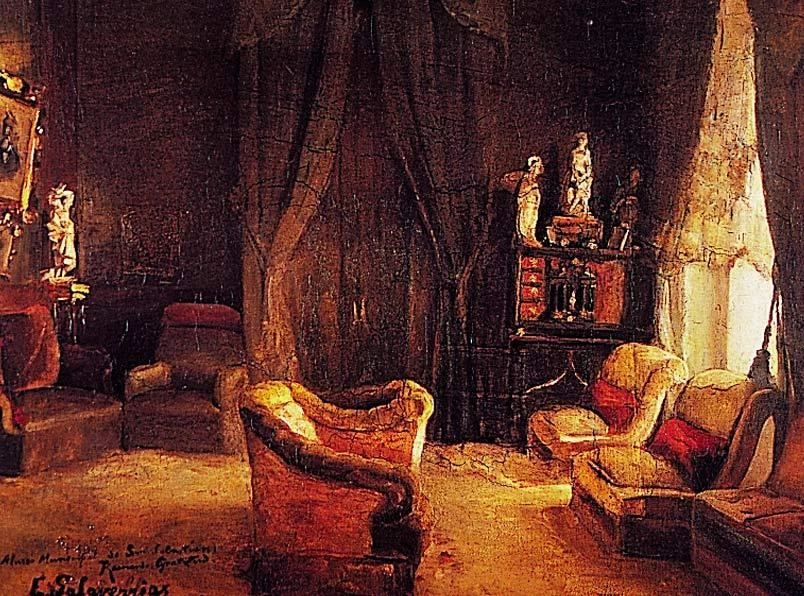

During Spain’s dark years, shadow was penumbra. The country was on the threshold of change, and the seeds of the century were germinating in its interiors. Before beginning to pulsate in immobile landscapes, the future throbbed in the dimness of bedrooms. Social transformations intertwine with intimate mutations, and the material changes that alter the public domain silently reverberate in the private sphere. The room absorbs the vibrations of the world, but this inner territory is also a uterus gestating larger metamorphoses. If we were to listen to this domestic womb, we would not only hear the tepid murmur of routine, but also the beat of new life. In such interior landscapes of turn-of-the-century Spain, the anthropological darkness of the patriotic pessimism of ’98 was perceived as an ambiguous penumbra.

Between the bedchamber of Ana Ozores and the corrala of Uncle Rilo lies an insurmountable pit burrowed by social stratification; between the anxiety of the unemployed Villaamil and the smug placidity of Antonio Azorín stretches a psychological abyss that is expressed by their domestic backdrops; and between the hut of Batiste and the boardinghouse of Doña Casiana is the material and moral distance that separates rural poverty from urban misery. It is with the wickers of social fracture, political dysfunction and economic violence that the settings of everyday life are woven. The city builds the house: the collective domain shapes private space. But it is in this sanctuary that the subversion of the public world is incubated, and in the shadow of the house burns the slow flame that will one day destroy the sleeping city.

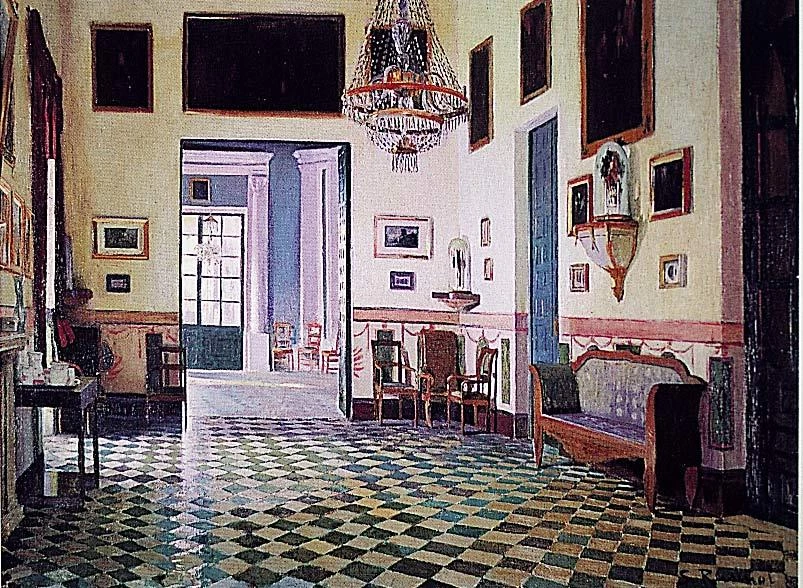

Interior of Viznar Palace (1898), by Santiago Rusiñol.

Study of Interior (1903), by Elías Salaverría.

Restoration and Representation, from La Regenta to Miau

The best portraits of the Restoration are the novels of Clarín and Galdós. In La Regenta (1884), Leopoldo Alas takes apart with clockwork precision the pieces forming the social mechanism of a provincial capital, and exposes with intricate irony the characters and scenes surrounding the sensitive, nervous and adulterous Ana Ozores; in Miau (1888), Benito Pérez Galdós satirizes the absurd universe of Madrid bureaucracy through the unemployed Villaamil and the frivolous women of his household, so obsessed with bel canto and appearances. The intimate atmosphere as the bourgeois space par excellence: this is the thread that connects the bedroom of La Regenta to the parlor of the Miaus, two interiors which braid psychological characterization with social description.

The bedroom of Ana Ozores is clean, tidy, austere and vulgar. Separated from the boudoir by garnet-red satin drapery, it had a commonplace gilt bed with a white canopy, a tiger-skin at its foot, and an ivory crucifix above the headboard, nothing much more. To the indiscreet Obdulia, there are no signs in it of a woman of elegance. “Absolutely nothing worth while. There’s no sex there. Leaving its tidiness aside, it’s just the same as a student’s room. Not a sigle objet d’art. Not one wretched bibelot. None of the things demanded by good taste and comfort. Just as the style is the man, so the bedroom is the woman. You know a woman by the bed she sleeps in... It’s such a pity... that such a precious bijou should be kept in such a miserable jewelbox.” Located at one end of the Ozores mansion, the Regenta’s chamber is an autonomous personal space that violates the ornamental codes of femininity.

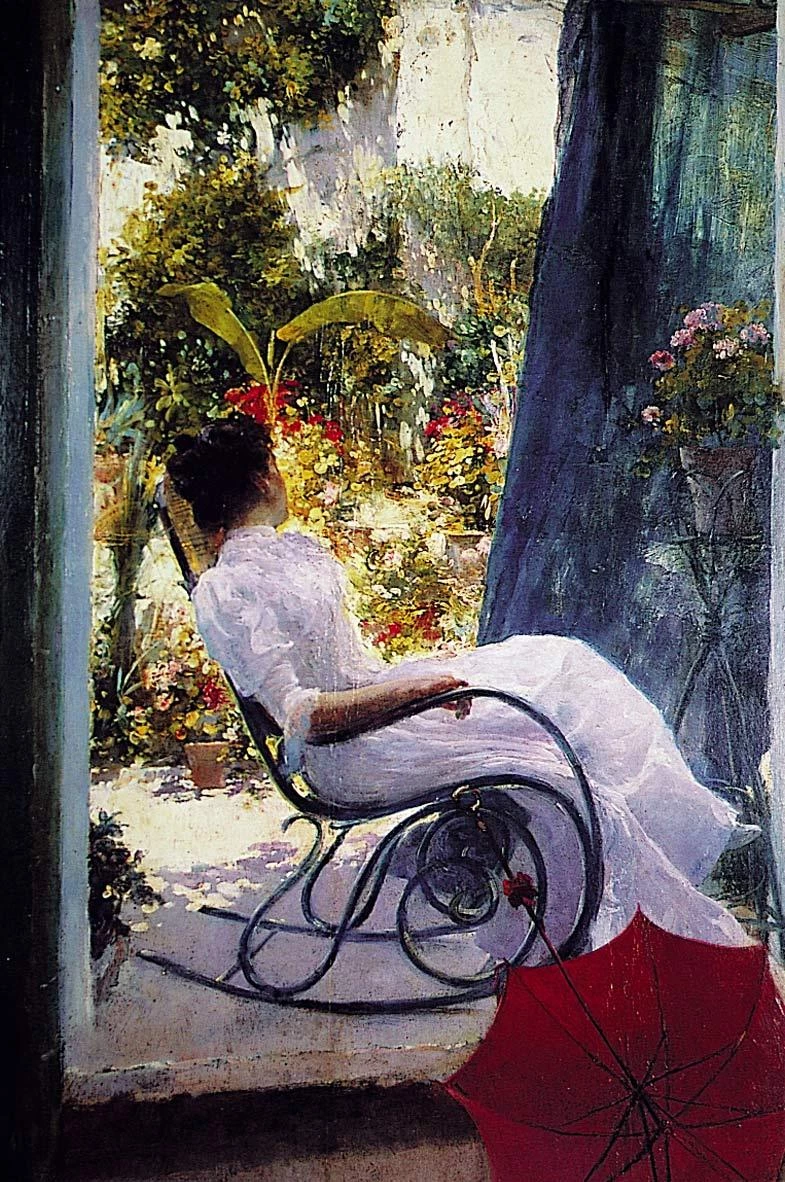

Study of Summer (1893), by Ramón Casas.

The parlor of the Miaus, in contrast, is a cluttered bazaar that combines an upright rosewood piano with gold-filleted, lacquered rosewood cabinets, Damascus chairs, wall-to-wall carpeting and the silk drapes that are Doña Pura’s most prized possession, all this enhanced by candelabra inside globes, the inevitable golden clock, and an infinite array of knickknacks and junk. But the piano is untuned, the clock unwound, and the carpet protected during the day with removable rugs, but nothing can ease Villaamil’s wife’s anguish at the thought of the economic predicament of unemployment compelling her to mortgage some of these treasured objects. “This idea always made Doña Pura shiver, because the drawing room was the part of the household closest to her heart, the true symbolic expression of the home.”

Ana Ozores, sensual and unhappy, draws the drapes, absently slips off her dressing-gown, buries her bare feet in the fur of the tiger-skin a suitor once gave her, stretches her limbs voluptuously, lets herself fall face downwards on the soft mattress, caresses the sheet with her cheek. “She took great delight in that tactile pleasure, which ran from her waist to her temples.” The trivial Doña Pura, in her turn, expresses her attachment to textiles by having the visiting ladies touch the silk of her curtains, rub it between their fingers and feel its weight, while shuddering with terror at the thought of parting with them. “‘No, no... the shirts before the curtains.’ Stripping bodies, to her, was a tolerable sacrifice. But stripping the drawing room... never!” It is difficult to imagine a clearer opposition between pleasure and appearance. The helpless naked body of Ana Ozores provides a critical counterpoint to Obdulia’s chidings and Doña Pura’s panic at the idea of naked bedrooms and parlors.

Necessity and Paraphernalia, in La Barraca and Antonio Azorín

The turn-of-the-century rural world had two opposed chroniclers, Blasco Ibáñez and Azorín. In La Barraca (1898), the republican journalist described peasant life and the social conflicts of Valencian farm country through the hardworking Batiste’s vain efforts to establish himself and his family as tenants on untilled land. Through Antonio Azorín (1903), the also Levantine José Martínez Ruiz reconstructed the character he used as an alter ego and pseudonym, and the timeless landscapes and everyday details of the fields in his native Monóvar. Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s random construction of the domestic sphere finds a pessimistic skeptical rejoinder in Azorín, who clutters his rural houses with nostalgic objects deposited by the passage of time.

Andalusian Indolence (1900), by Julio Romero.

The Siesta (1900), by Julio Romero.

Batiste’s hut is a declaration of faith in hard work as a tool with which to change one’s world. The former mill worker and carter becomes at once a farmer, a carpenter and a bricklayer, as ready to move earth and sow seed as he is to rebuild his ruined shack. The thatched roof, the cracked walls, the stockyard and the stable, the well and the vine arbor: everything is reconstructed with materials salvaged from the rubble, until finally, “from the half-open door, one can discern the new shelf with its white tiles and green fat-paunched jugs”, and the family’s miserable paraphernalia – “consumptive cushions, mattresses filled with scandalous corn leaves, straw chairs, frying pans, pots, plates, baskets and green bed benches” that arrived one day piled up on a cart – is now surrounded by the modest, proud prosperity of a house, the fruit of hope and tenacity.

Courtyard of Sitges, Interior (c. 1892), by Santiago Rusiñol.

Antonio Azorín describes his own country house in Sax with laconic precision. Flanked by the bulk of the oven and the rooms of the farmhands, it forms a small square with a chapel and a coach house, beside which are a cistern and an irrigation pool. The house has spacious halls, a library with four thousand volumes, chambers with slanted ceilings, dark granaries, an earthenware jar for storing oil, a large cellar, an oil press, two kitchens with wide-hooded smokestacks, pigeon lofts, stockyards and barns... And in the manner of a concise inventory, the writer gives us two leads into the space and furniture. “The study has a high ceiling and clean walls. It is furnished by two armchairs, a rocking chair, six chairs, a pedestal table, a desk and a console table.” “The bedroom is large and bright. Light shines in through the balcony... The furniture pieces are an iron bed, a marble washstand with a mirror, a chest of drawers with branches and angels in white inlay, a coat stand, three chairs, a green armchair.”

Woman in Library (1900), by Ramón Casas.

By the Stove or The Love of the Hearth (1896), by Manuel Cusí.

The sharecropper and the landowner are separated on the social ladder to a degree manifested as much in their dwellings as in their furniture and household items. The hut is replaced by a house “of labyrinthian rooms,” the well becomes a cistern and a pool, the household effects that Batiste fits on a cart go on to take up pages of detailed descriptions in Azorín, and even the shelf of earthenware jars that is the pride of the tenant worker has its superior version in the writer’s Monóvar house: “On the shelf are four jars, and on each jar, resting on its wide mouth, is a jug oozing bright drops. And there is also a large jar with a lid, and a small bowl on a support nailed to the middle of a picturesque tile painting, and a clean towel hanging on the wall that flaps with the wind blowing in from the courtyard.” But beyond such detailed multiplication of items, there is an even greater emotional distance between the peasant who builds out of debris the necessary landscape of an uncertain future, and the landlord who contemplates the objects of his intimate landscape like pieces of debris left by the passage of time, remains of the inevitable shipwreck of life.

Rooms of Urban Survival, on the Margins of La busca

Pío Baroja’s interest in society’s margins made him an excellent reporter on the misery of city life at the start of the century. In La busca (1904), part 1 of his trilogy La lucha por la vida, Baroja describes with accuracy two of the most humiliating forms of urban habitation, the boardinghouse and the corrala. Compared to the overcrowding and insalubrity of rooms in both cases, the living conditions of peasants were enviable; rural poverty rarely reached such degrees of domestic degradation. The houses of Doña Casiana and Uncle Rilo hardly deserve to be called so: her boardinghouse is a dark, stinking den, and his, a sordid, infected corrala. Vertical segregation prior to the elevator, which stratified neighbors by floor level, from the prosperous low stories to the modest attics, and horizontal segregation, which distinguished the respectable rooms at the front from the servants’ quarters on the inner courtyards, amount to organic structures when compared to the random squalor of rooming houses.

In the gloomy boardinghouse, always in darkness, lodgers are guided by a gaslamp over the door, by “the vague brightness diffused by a rubber butterfly swimming in the water and oil of a glass fixed to the wall by a tin ring” at the entrance, and by the smoky footlights of the rooms. One of them is occupied by three women of dubious virtue, Doña Violante and her daughters: “The three slept in an inner room facing the yard, from whence came the repugnant reek of fermented milk of the stables below. There was no room for anything, not even to move around; the unit they had been assigned... was a boxroom containing two narrow iron beds, with a folding bed inserted into the small gap in between.” Darkness and fetidness are the common curse of these unhealthy rooms.

Celestine (1906), by Ignacio Zuloaga.

Uncle Rilo’s corrala surpasses even this physical and biological degradation. In the galleries of rooms surrounding two foul-smelling courtyards, “one could see nothing but dirty clothes hanging on rails, mat curtains, patchwork quilts of motley colors, blackened rags placed on broomsticks or hung on ropes stretched from one pillar to another, blocking out light and air.” The main courtyard is full of junk, rubble and garbage; the drain clogs here when it rains, giving rise to “the unbearable stench of black water.” A corridor “full of filth” joins it to a smaller courtyard, “which in winter becomes a fetid swamp.” According to the novelist and physician Baroja, “in a more humid climate, the corrala would have been a source of infection; Madrid’s wind and sun, the sun which cures rashes on the skin, took care of disinfecting this den.”

These rooms of urban margins are even more somber than the sad “three-keyed houses” of some factories, where workers take turns to sleep on beds; the crowding and exploitation of the industrial proletariat does not worsen their predicament with the cruel stratification of residential squalor. Here, in fact, debasement has infinite gradations. In the boardinghouse, Doña Violante and her daughters are given a repulsive tiny room, “one in accordance with the small board and lodging and the irregular payment thereof,” but Petra the maid gets something even worse, “a dark cell full of old junk,” a hole where the heat is stifling and she sleeps on the floor with her son Manuel. Similarly, the corrala accommodates “all grades and nuances of misery.” For example, “rooms around the inner patio were cheaper than in the large courtyard; most would cost twenty to thirty reales; but rooms could be had for two or three pesetas a month: dark boxrooms with no windows whatsoever, built into the gaps of staircases and under the roof.” While waiting for the hygienic revolution of light and air, this segregated and satanic city brewed a social revolution in its gutters.

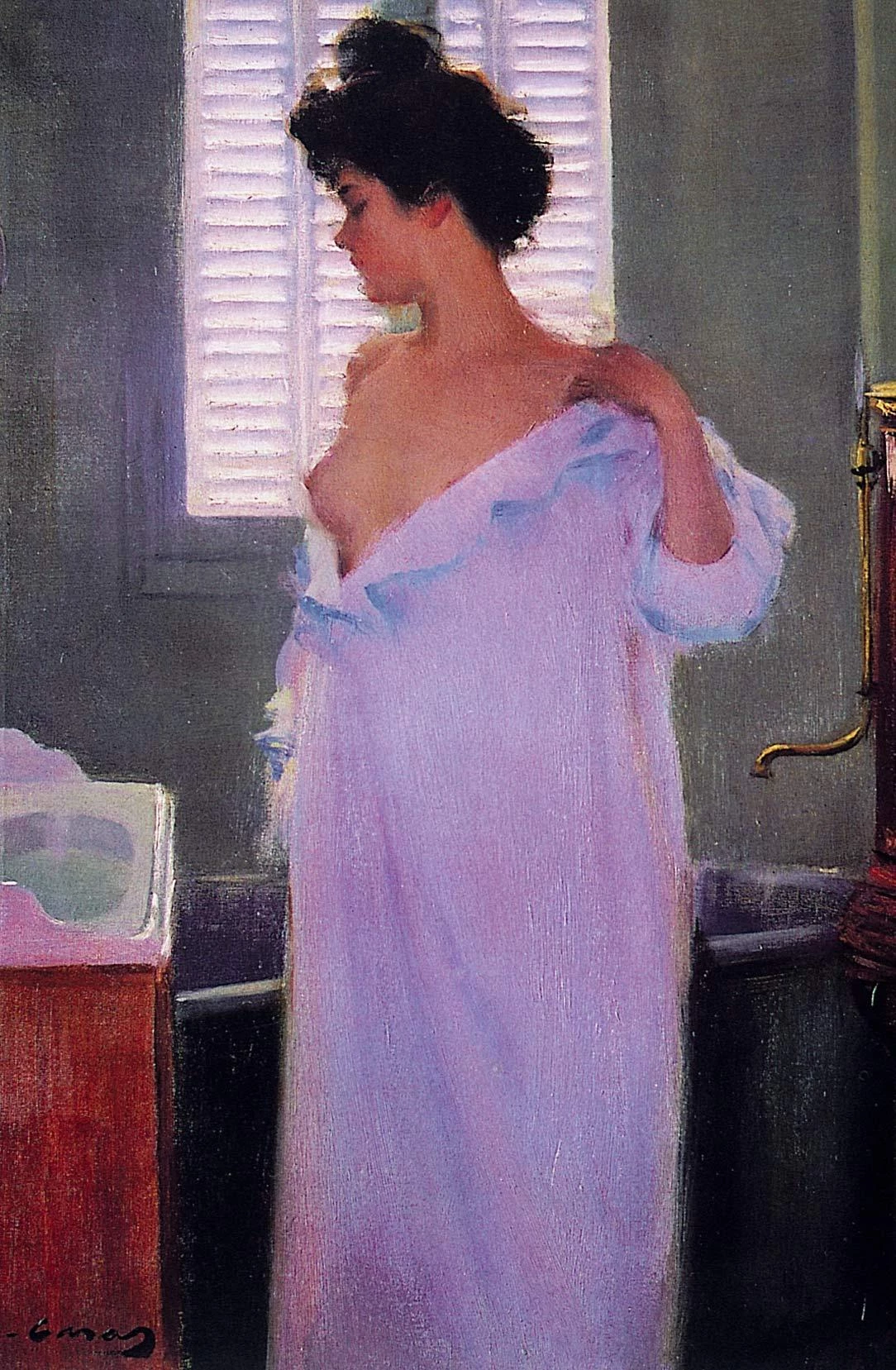

Before the Bath (1895), by Ramón Casas.

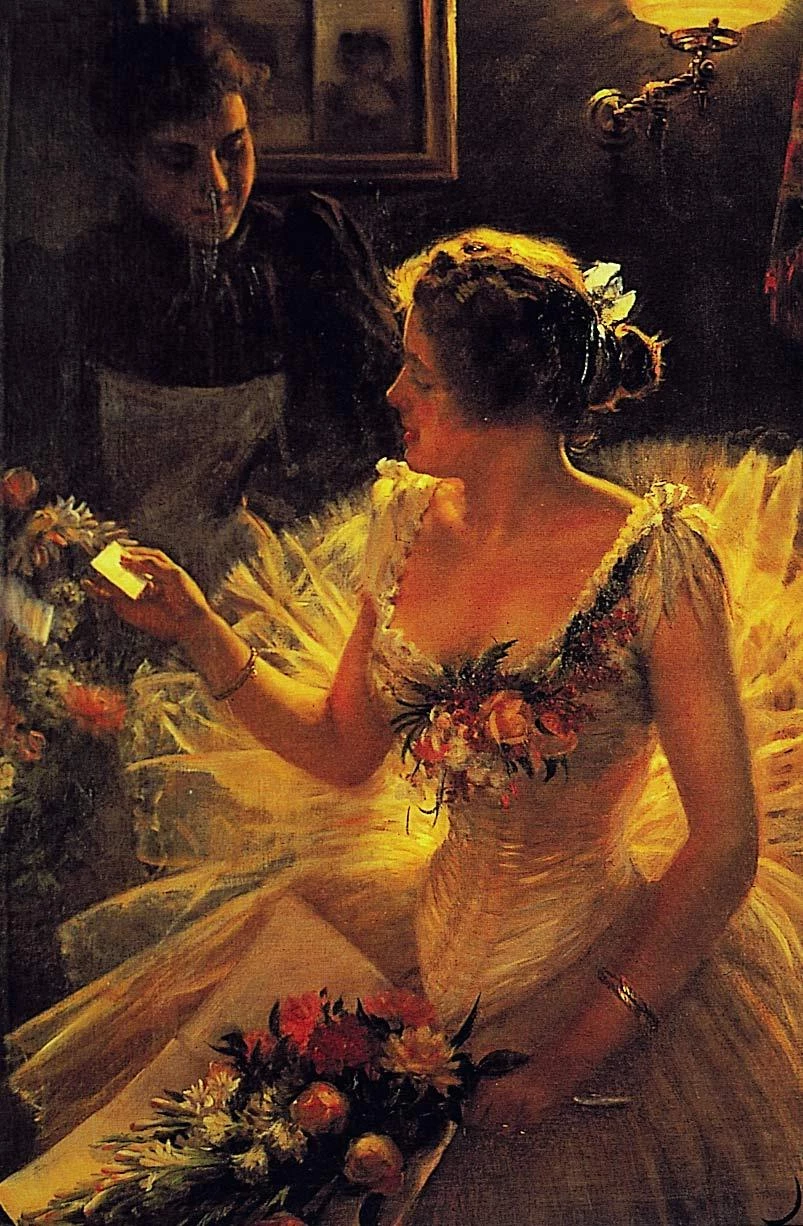

In the Dressing Room or Gaslight (1895), by Manuel Cusí.

Lights and Shadows of the Century, through Madrid callejero

The 20th century started late in Spain. The introduction of gas, and later of electricity, would change the landscape of urban housing, but during the first decades the bulb coexisted with the oil lamp; people continued to use braziers, stoves and pavilions over beds to combat the cold; and it took running water a while to replace the jugs and washbowls and the portable bathtubs, which were still being advertised in Madrid well into the century. By the early years the capital boasted voltaic arches and streetcars, but the same smoky boilers that asphalted the Puerta del Sol served to warm up the city’s ragged homeless on winter nights. The drama of Ana Ozores, the suicide of the unemployed Villaamil and the burning down of Batiste’s hut speak of the cracks of a social, political and economic system, in the same way that the sordid uprooting in La busca of Manuel, a child adrift in a city assaulted by misery, reveals the disaster of an intolerable regime.

The Rastro (1922), by José Gutiérrez Solana.

In 1923, the painter José Gutiérrez Solana described the Madrid callejero, and took the opportunity to settle scores with the Generation of ’98, “well-meaning men of action and prey who were capable of everything, but ended up digressing in a most lamentable manner.” The quixotic “Spaniardization of Europe” had by then given way to the reticent acceptance of a late modernity. The painter and chronicler scoured the Gran Vía’s “buildings à la moderne, petulant, all very white,” and portrayed the destruction of the city’s entrails: “Inside the remains of demolished houses, which resemble giant boxes, one sees the staircase... deep-red wall-paper with branches of yellow flowers leading to the bedrooms and dining room. On the ground floors one notices the black stain of the kitchens... Beside the entrances to the buildings about to be torn down... are the personal effects of the residents: chests, straw mattresses, kneading troughs and earthenware jars, the sewing machine... and piles of clothes, iron beds, chests of drawers, console tables, washbowls, and the broken white-horse tricycle of a child.” This landscape of rubble and transit represents well the painful but necessary passage of a Spain in penumbra at the turn of the century.