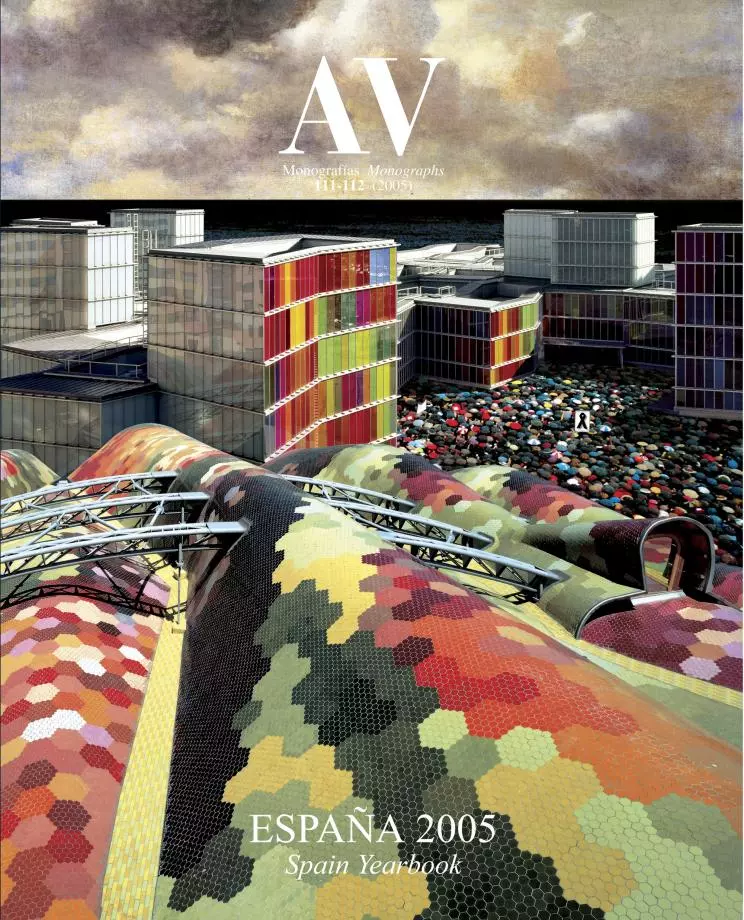

Tragic Trains

After Manhattan’s 9-11, the Madrid bombs of 11 March in four commuter trains have tragically revealed how the horizontal city is as fragile as the vertical one.

The four planes of 11 September were four trains on 11 March. Whereas in Manhattan two crafts successfully destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, in Madrid the chance factor of timers behaved in such a way that the two convoys meant to explode simultaneously in Atocha failed to put the structure of the station to the test. The terrorist attacks produced no great architectural damages, but its tragic count of victims – two hundred dead, over a thousand wounded – reveals the extraordinary vulnerability of the infrastructures that support urban life. By bringing down office skyscrapers, 9-11 attacked the towering emblems of economic power. By blowing up the guts of suburban trains, 3-11 has punctured the arteries that irrigate the spread out body of the metropolis, showing how the vertical city is no more fragile than the circulatory system that sustains its horizontal sprawl on the territory. The city bleeds just as much, with this tissue torn, as after a crack shot at its nucleus.

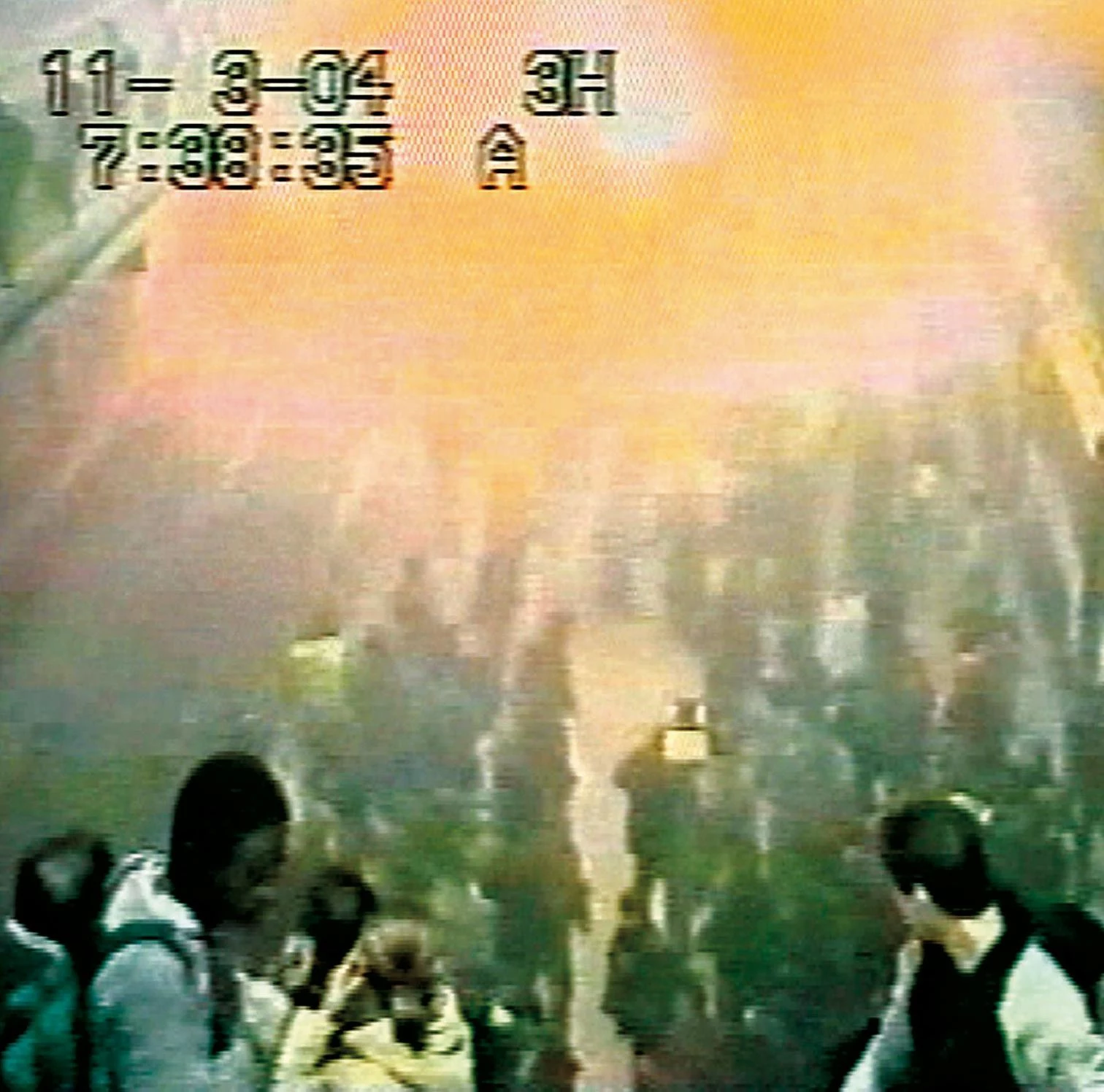

The attack recorded on the station’s cameras, Atocha’s profile, and rescue teams by one of the bombed trains.

Madrid will not suffer any less than Manhattan. It will repair material damages faster, but the wound inflicted on the social capital of mutual trust will take much longer to heal. Fear of tall buildings and trains will give way to the everyday demands of cities constructed around the elevator and the subway. The trauma of watching people leaping into the void and bodies mutilated by a bomb fades with time. Wariness of others, however, worsens inexorably, leading to an exchange of freedom for security. If people of almost a hundred nations perished at the World Trade Center, among the casualties in the morning rush hour trains headed for Atocha were numerous immigrants from Latin America, Eastern Europe, and North Africa. But their toll of blood will not diminish the xenophobia that is nourished by Andean drug mafias, by delinquent gangs of the former socialist countries, and now, apocalyptically, by terrorist networks of Islamic fundamentalism. We shall see a trafficker in every Colombian, a gunman in every Russian, a dynamite bearer in every Muslim.

With its predictable repercussion on immigration policies and its inevitable influence on the make-up of the urban population, diversity being as potentially enriching as it is materially difficult to administer, such criminalization of the foreigner is but an extreme manifestation of distrust of one’s fellow man or neighbor, a corrosive fluid that capillarily penetrates the social tissue and that with its gut fear dissolves the routine mortar that gives cohesion to the city. An attack like Madrid’s is terrible not only in its cruel toll of mutilated lives or in its bringing to light the vulnerable nature of transportation networks, but above all, because it undermines the absentminded trust that allows people to live side by side. It is frequently stressed that the contemporary city is governed not by the architectural logic of monumental or anonymous buildings, but by the engineering logic of the infrastructures that facilitate mass movement. This is why Madrid’s horizontal wound is no less detrimental to urban health than the vertical void of New York City. But all too often we forget that, beyond physical constructions, the essential material of cities is its inhabitants and the hank of mutual trust that binds their destinies together, connects their expectations, and regulates the economic and demographic flows that condition their future.

The city as a network has been devastated by a network of terrorism. The dead have been buried and railway traffic has resumed, but the delicate fabric that knits us together, ripped by trauma and suspicion, has not mended entirely. The networks of mobile phones collapsed on the morning of the attacks, saturated as they were by calls of alarm that tried to weave a web of comfort, however fragile. But this network of information and succor used the same gadgets that were utilized as detonators in the explosive backpacks. In a tragic sarcasm, though also with a lyrical pathos of unspeakable pain and violent emotion, throughout the aid operations the cellphones of the dead did not cease to ring. The unanswered calls are the loudest image of a broken down network. Buenos días por decir algo (‘good morning for lack of something truer to say’), cried radio broadcasters in unison, over and over again. Such narcotic refuge in the rhetorical greeting clearly reflects the collective panic and personal disorientation of the occupants of that Hertzian space who in other crises of our communal life, particularly that of 23 February 1981, were able to create for us a network of security, but who on 11 March 2005 could offer the city no other consolation than a vacuous, analgesic sentimentalism.

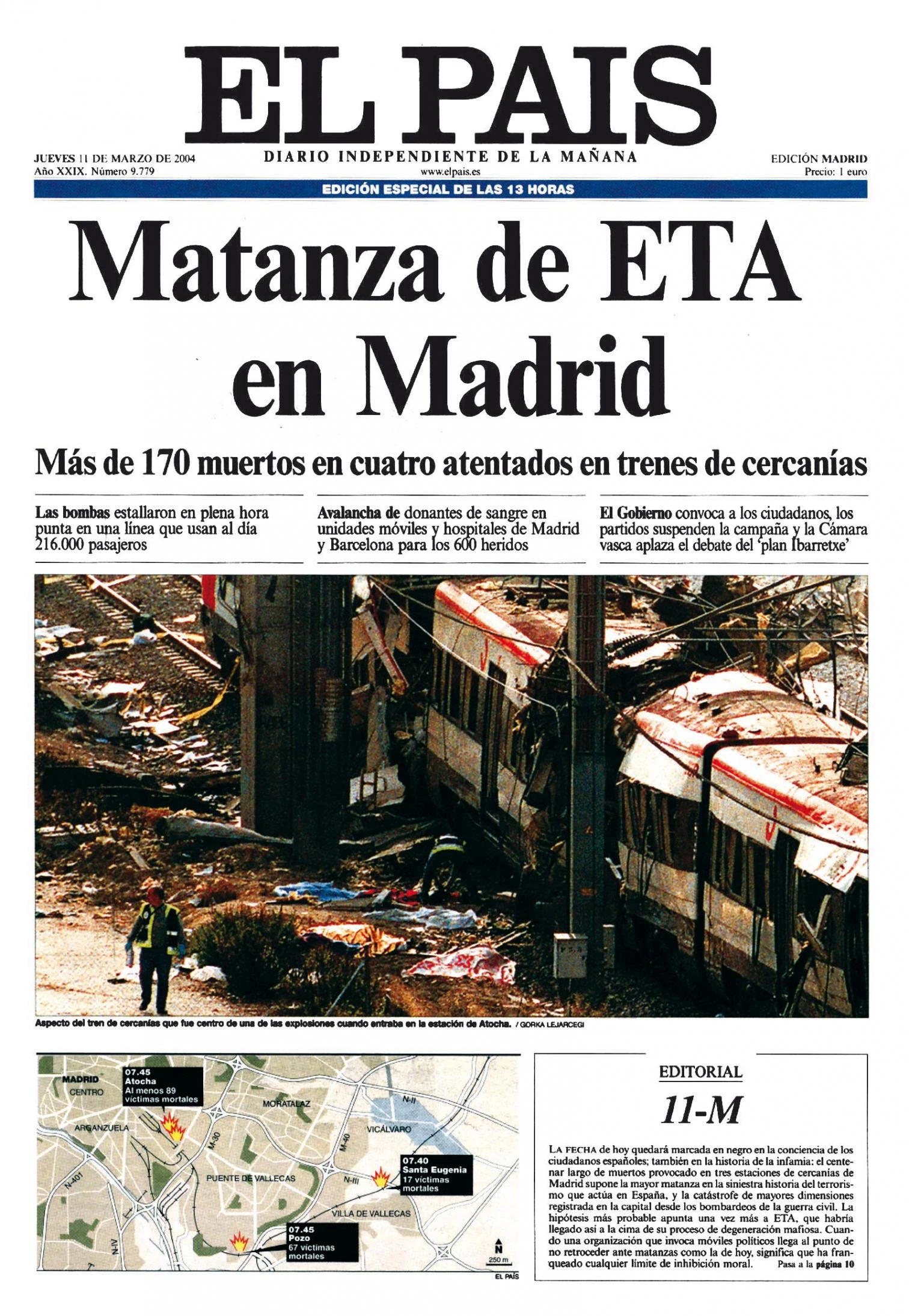

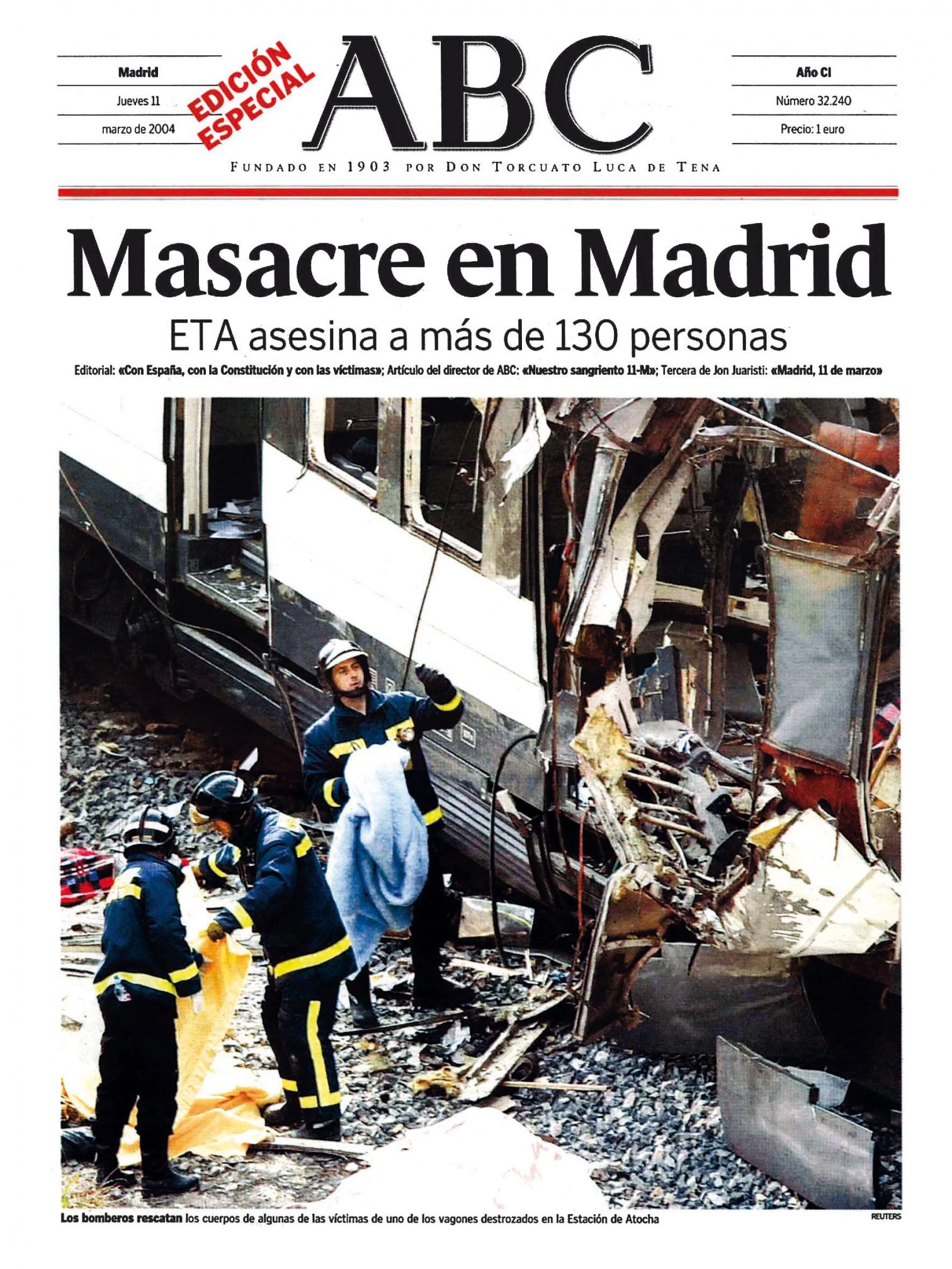

Front pages of the special editions of the Madrid newspapers on 11 March, the mass demonstration of protest held on the 12th, and a spontaneous memorial in the hall of Atocha Station with notes, flowers and candles.

Madrid now, like New York then, is colonized by commemorative altars and Mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón has hastened to propose a memorial. I amnot sure it is new monuments the capital needs at this dramatic crossroads. Foreign television network correspondents flown here to cover the catastrophe, including CNN star Christiane Amanpour, have chosen the solemn brick drum of Atocha Station as background for their reports. This architectural icon designed by Rafael Moneo probably has the uniqueness and the monumentality necessary to accommodate the memory of the monstrous railway massacre, inevitably linked as this is to the name of the terminal for trains 17305, 21431, 21435, and 21713. (By a strange coincidence, the American and British TV channels would complete their stories with images showing President Bush – indelibly linked to Aznar by 9-11 and the Iraq war – laying a wreath before the black-banded flag at the Spanish Embassy in Washington, D.C., a building recently finished by Moneo, so that the architectural backgrounds of both items were works of one same architect.)

Crystallization in symbols, however, has a chance component that resists deliberate designation. This is something that did not seem to matter to the inhumane organizers of the Madrid holocaust, who cabalistically chose to carry out the attack 911 days after 9-11 and fiendishy claimed responsibility with a videotape deposited in a wastebasket placed between the Mosque and the Morgue along the M-30 highway: two emblematic constructions on the edge of Madrid’s major beltway. The massacre was followed by wakes in both buildings. But in the brief passage from one to the other, from the Muslim faith to civil mourning, the sinister Al Qaeda managed to expose the vulnerability of the open societies of the West, write a new chapter of history on the confrontation between Islamic radicalism and “the new Christian crusaders,” and intervene decisively in the political process by putting a city, a whole country, on its knees. Capital of disgrace and capital of pain, Madrid today is a station, a mosque, and a morgue.