A certain Tamayo has caused an earthquake in Madrid’s regional parliament. Projecting impassiveness, the deputy who has broken the socialist party discipline poses meekly in the office of his lawyer on the Plaza de Castilla, behind him a pallid landscape of blocks and towers that hangs like an Antonio López painting. His friend the developer Bravo, distracted accomplice in the maneuver that has prevented the left from governing in the region, is framed in the photograph with the classical orders of his postmodern office in Villaviciosa de Odón, and there is a peculiar agreement between the awkward double-breasted suit and the pilasters, moldings, and pediments of the main entrance; on the way to the parking lot, a shabby construction that reeks of a playful Rossian classicism provides a second symbolic backdrop to the walk ing figure of the real estate shark. Fourteen years ago, a certain Piñeiro was the protagonist of another case of “roguism” in the same Madrid assembly. The rogue was from the other party, however, and newspapers now reprint the picture of him at the entrance of the offices of a property developer with a Roman name and classicist laurels for a logo: The figurative rhetoric of grandiose architecture serves the miserly ambitions of uncertain personalities, and the cracked solemn order of the ancients hardly conceals the trivial and greedy disorder of these modern-day urbanizers.

The routinary layout of the neighborhoods that fill the metropolitan territory is interrupted by the emergence of signature buildings. The landmark of Madrid’s Sanchinarro area (below) will be a housing slab by MVRDV.

Architects are skeptical about urbanism, but surely the shape that the city and the territory around it takes is more important than its singular pieces. Sequestered by the symbolic magic of some signature works, we close our eyes to the anonymous expansion of the formless city. And sheltered by the intellectual sloth of mediatic mantras – land speculation, the mafia of brick, real estate corruption – we refuse to admit that garbage urbanism is consuming and crowding metropolitan territories as a material manifestation of prosperity and as a geographic expression of democracy. Like junk food or garbage television, the residential developments of poor architectural quality that proliferate in the urban peripheries respond to a huge social demand: McUrbanism mixes with Glam urbanism, and the multitude feeds the real estate bubble with the servitude of mortgages. The consumer sovereignty that reigns supreme in food and leisure also governs the house and the city, oikos and polis, and this etymological root of economics and politics sublimates the postmodern hypostasis of market shares and election polls in the single substance of the audience index, a cartography of conscience eventually transferred to the map of the territory.

Fruto de una demanda social imparable, las promociones residenciales de escasa calidad son paradójicamente una manifestación material de la prosperidad y una expresión geográfica de la democracia.

Beyond the Madrid anecdote, which simply highlights the known secret that political parties amalgamate ideas and interests – an on the other hand legitimate circumstance that in many mature democracies is manifested through organized movements and explicit lobbies – our political leaders’ penchant for submissive parliaments reveals the defensive reflexes of bureaucratic elites that are helpless in debate and fragile in transparency, for the stability of the system demands that the essential never be put into question. And the essence of the territorial model rests on the placid acceptance of consumerist urbanism, replacing collective decision-making on the city with a host of fragmentary interventions, products of shady agreements or dark guesses, which colonize the landscape with built junk. Neither the disloyal manipulations of deputies frustrated by breaches of internal pacts, nor their bosses’ highflown reactions to their insubordination, nor the opportunistic maneuvers of their electoral rivals in the face of the manifest decomposition of socialist leadership shed light on the mechanisms that shape Madrid’s territory. The ensuing string of accusations, with its spluttering of bribes and vote-buying, is a firework with black flashes of lightning illuminating some sewers of local urbanism, but that protects with its unanimous night the city agreed on by real estate democracy.

Exotic Dressing

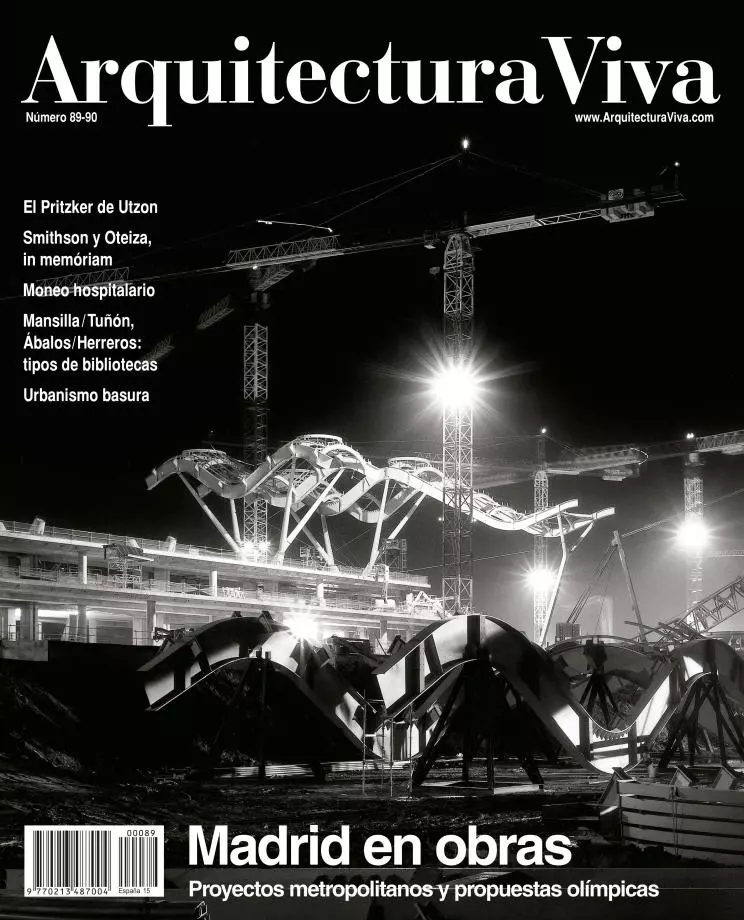

This featureless urb calls for flashes of signature to alleviate its narcotic anonymity, and sophisticated architectures lend themselves as alibis of the generic city. In the city of Madrid, the apartments commissioned to a hetetoclite galaxy of international firms – from MVRDV or Chipperfield to Morphosis or Legorreta – serve as an exotic dressing to the deplorable PAU operation, which has devoured the available soil with the homogeneous mediocrity of its routinary schemes. In the larger territory of Madrid’s region, the cultural centers assigned by the government to young talents are a futile exorcism and symbolic smokescreen amid the tenacious encroachment of the real estate mire that floods the landscape with its dull residues, cooked in public departments of urban planning frequented by builders and landowners, and in development companies with politicians on their payrolls and offices adorned with the glitz of classical architecture. But there are no great dramas here. This at once perverse and pacific system is a self-inflicted disease, so we need not investigate symptoms in pursuit of surprises: its etiology is trivial. The most cynical ones will say that in the final analysis, democratic politics is but the management of conflicting interests and the arbitration of power or profit, questions that preclude clear-cut ideas or forms, but which in their conformist indifference protect us from totalitarian Utopias.

In the immaterial universe of media and images, accelerated communication through emblematic objects conceals context while making it more dynamic. The seductive gleam of singular architectures keeps the ugly things in penumbra, but this Potemkin-style cover-up is corrected by the genuine impulse that novelty impresses upon the everyday life of the ordinary citizen. Maybe that is why symbolic pieces (including statuary and urban furniture) become so disproportionately important both in our perception and in municipal debates, at the expense of great structural decisions, which lose polemic prime time and often go altogether unnoticed. It was not the PAUs but the proliferation of old-fashioned urban furniture on the city’s sidewalks that made architects demonstrate against Mayor Álvarez de Manzano, who had his biggest clash with the intellectual elite, unreceptive as it is to Disney-style folk cuteness, on the issue of the statue of La Violetera, installed by his predecessor Rodríguez Sahagún. And of a sculptural nature, too, are the first artistic gambits of his successor Ruiz-Gallardón, who with an erroneous populist instinct has sanctified the pathetic trilithon dictated by a dying Dalí, the translation of a two-dimensional image, but who has also admirably and rigorously defended the goddess of the Plaza de la Cibeles from the excesses of Real Madrid victory celebrations, even at the cost of provoking the unprecedented ire of a team that seems not to make the connection between its exorbitant salaries and the club’s securing of municipal go-ahead to make a real estate business of the Ciudad Deportiva.

Absorbed in their solitary pleasures, signature architects contemplate urbanism with bewildered fascination. They know that cities need the mediatic adornment of their works, and that art transforms the everyday into something unique. But they also know that the most powerful Midas is the legislator who can transform the use allocated to land, turning into gold all that he touches. To their surprise, in their alchemic manipulations these apprentices of Harry Potter find that the urbanist’s magical powers are greater. And sheltered by cryselephantine critics, who defend both their golden touch and their ivory tower, the architects of Venus prepare to seduce the urbanists of Mars, convinced that the aesthetic appeal of signature works must be fertilized with the muscular energy of the city if healthy offspring are to be engendered. But if we fly over the bleak uplands built on our peripheries, we might come to the conclusion that urbanists are not from Mars, but from Uranus. We might as well adopt.