European Eves

The architectural year that has just ended can be summed up in four names: Juan de Herrera, Sverre Fehn, Aldo Rossi and Frank Gehry.

The eves of Europe come with variable weather. The year of convergence toward a single European currency has been both sunny and rainy for Spain. Sunny in the economic and social fields, with a rise in stock values and optimism; rainy in the political and meteorological realms, with the tension caused by conflicts in the media and the courts competing with the storms provoked by El Niño. So have cloudy and clear days alternated in the cultural field, where alarm at the diffusion of conservative folklorism has been compensated by the festive mood of much awaited inaugurations. The year of architecture can be summed up in four names: Juan de Herrera, the centenary of whose death has served as prologue to a complex debate about Spanishness; Sverre Fehn, whose winning of the Pritzker Prize initiated a chain of Scandinavian celebrations; Aldo Rossi, whose sudden demise closed a chapter of contemporary architecture; and Frank Gehry, who on completing the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao reached the peak of his career while providing a great symbol for the turn-of-the-century culture of spectacle.

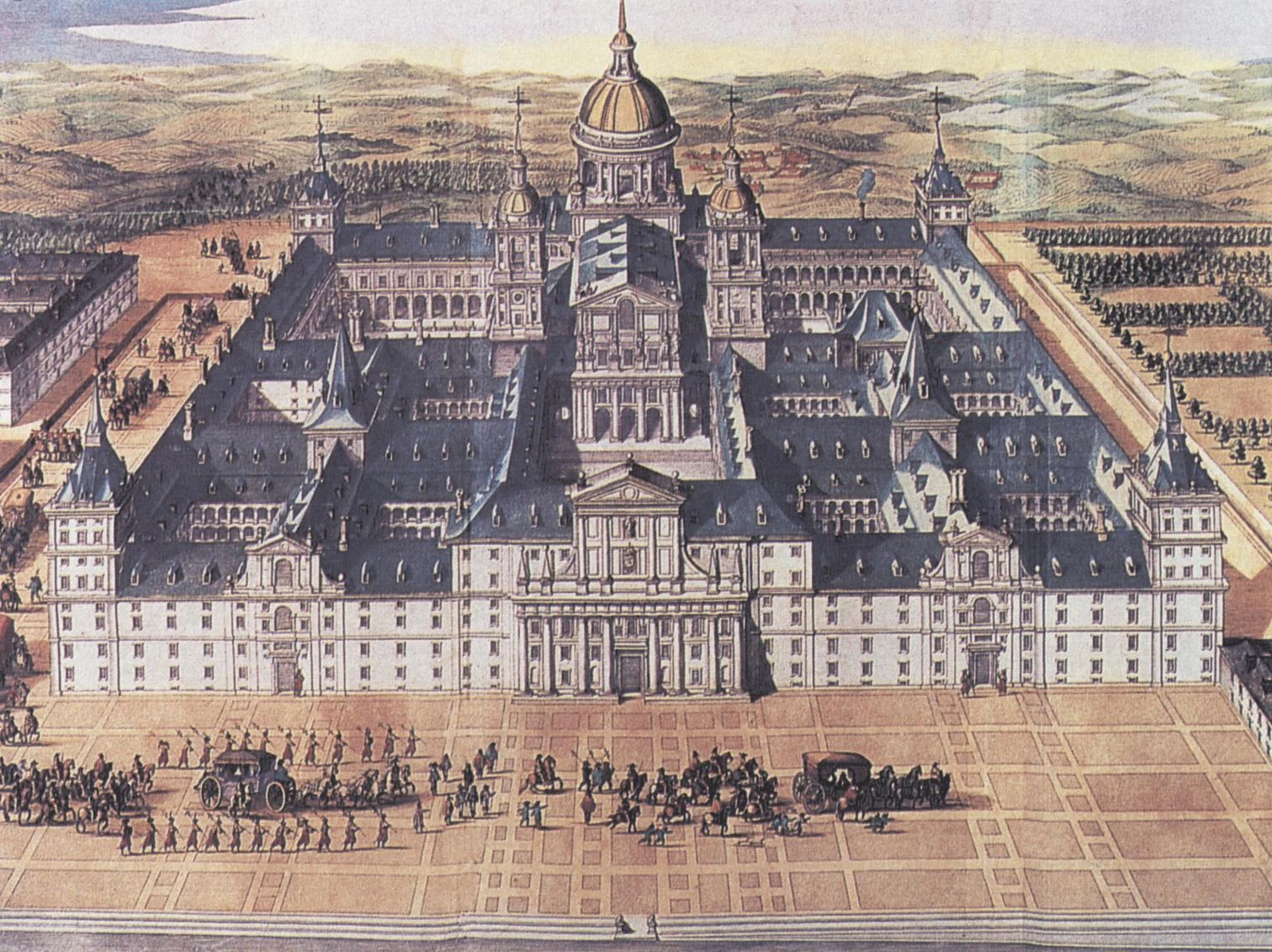

January marked four hundred years since the death of the architect of El Escorial, inciting a complex debate about Spanishness which will culminate in 1998 with the centennial of his patron, Philip II.

Spain’s Winter

January’s fourth centennial of the death of Juan de Herrera, architect of El Escorial, was a cold celebration. Nevertheless it aroused an appetite for a new revision of Spanish history that inevitably touches on his patron, Philip II, preparations for whose own centenary in 1998 have already begun to bear fruits that will tie up with another patriotic and cultural commemoration, the hundredth year since the disaster of 1898. Probably Spain’s most important architect prior to Gaudí, Herrera was an intellectual whose stature grows with time, parallel to that of his king, in turn a Renaissance Maecenas and administrator whose figure is only now being severed from the somber overtones that were attached to it by the propaganda of religious wars and his association with the imperialist dreams and Herrerian classicism of postwar Francoism. Such revised views of the history of Spain are gaining ground, though not without political and educational debates between advocates of nationalist affirmation in some regions, and the efforts to establish a new European identity. An identity, by the way, which the designers of the euro bills have found in the continent’s successive architectures, and which in March the jury of the European Mies van der Rohe Award encountered in the geometric monumentality of Dominique Perrault’s Grande Bibliothèque: the Parisian Escorial of Mitterrand, a republican monarch who like De Gaulle defended a Europe of fatherlands.

In spring the Norwegian Sverre Fehn won the Pritzker Prize for a lyrical and tenacious career characterized by a devotion to construction and landscape, most evident in his Glacier Museum of Fjærland.

Scandinavia’s Spring

The awarding in April of the Pritzker Prize to the Norwegian Sverre Fehn began a streak of Scandinavian festivities that was prologued in 1996 by Copenhagen’s turn as European culture capital and is to culminate in 1998 with Stockholm’s and the centenary of the Finnish master Alvar Aalto. The architect of the Glacier Museum and of the Nordic Pavilion in Venice was feted for a lyrical and tenacious career based on his devotion to construction and respect for landscape: two Nordic virtues not too evident in some of the recent emblematic buildings of Scandinavia, such as the Museum of Modern Art of the young Soren Robert Lund in Copenhagen or the Museum of Contemporary Art of the American Steven Holl in Helsinki, but overwhelmingly patent in the Museum of Modern Art and Architecture by Rafael Moneo in Stockholm, perhaps because the architect recalled his training with the Dane Jørn Utzon. In any case the coming Aaltian commemoration, with its numerous exhibitions and tributes, will reseal the connection with the best of that fertile Scandinavian tradition.

Summer took the life of the Italian Aldo Rossi, whose ‘Grand Theater of the World’ embodies the metaphysical poetry and cult to memory that sum up a most influential oeuvre of the latter third of the 20th century.

Summer’s Ashes

August took the life of the American Paul Rudolph and summer ended in September with the death of the Italian Aldo Rossi, one of the great ideological and formal renovators of contemporary architecture. With his metaphysical poetry and his parallel cult of geometry and memory, the Milanese changed the course of architecture and urbanism of the final third of the century; but his elegiac defense of the traditional city and historical types has been rejected by the latest generations of architects, led by personalities like the Dutch Rem Koolhaas, who preach a return to modern experimentalism and are fascinated by the colossal scale of urban developments in the emerging economies of the Pacific. The Documenta of Kassel, which gauges the arts every five years, precisely chose the Rotterdam architect as a point of reference through an exhibition on the chaotic urbanization of southern China. Nevertheless, the handover of Hong Kong in July and the stockmarket and monetary quakes that have shaken Asia during the second half of the year put a brake on the vigor of a continent which has also welcomed a work of Rossi and the final phase of Rudolph’s career.

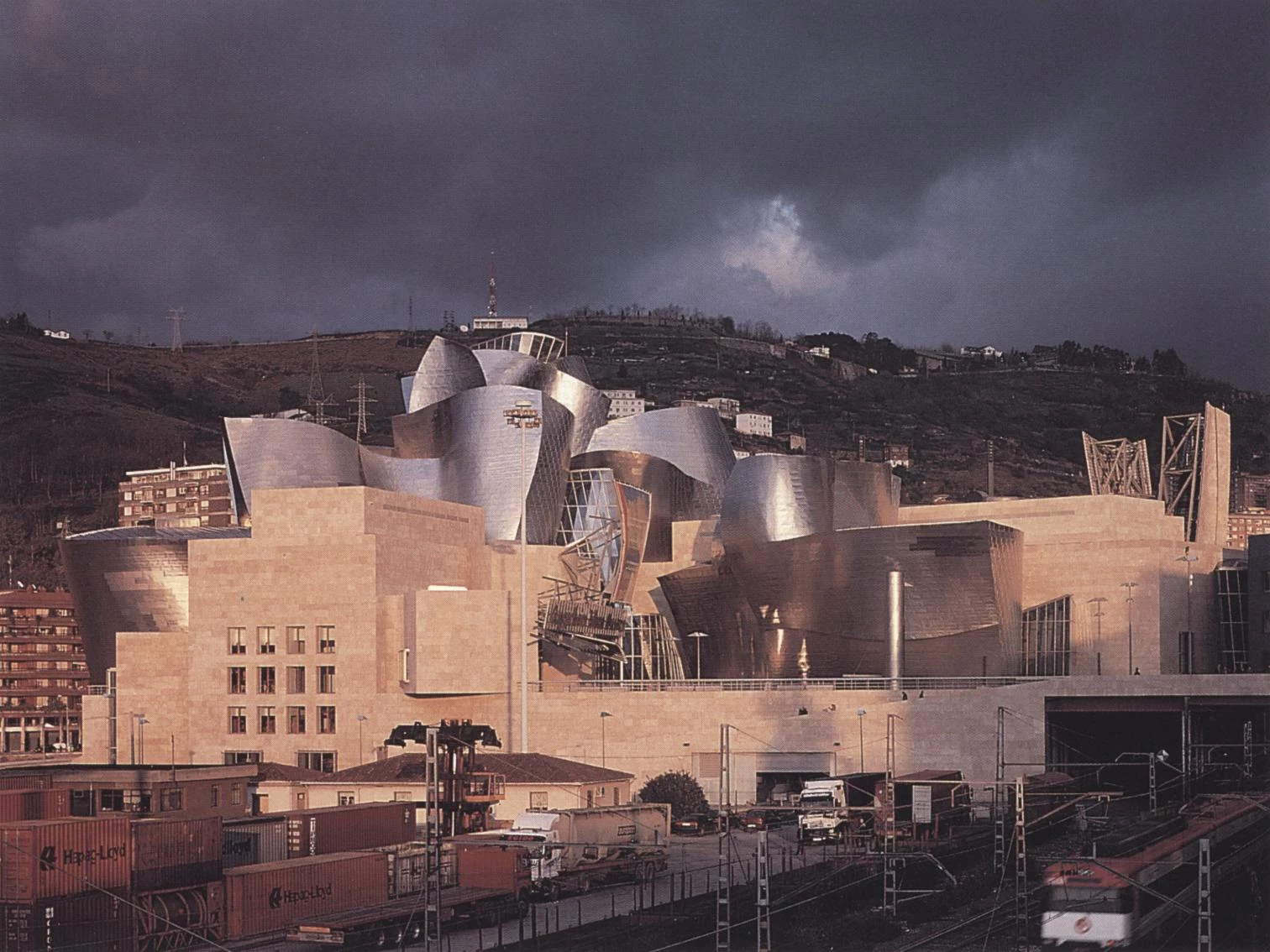

All of autumn’s limelight was directed at the Californian Frank Gehry, who opened the huge titanium sculpture that is the Guggenheim Bilbao, a symbol of the Basque Country’s cultural and economic regeneration.

Autumn’s Spectacles

The big star of the fall season was the Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao, the October opening of which was a major triumph for both its author, the Californian Frank Gehry, and the Basque Country, which has made the sculptural titanium building a symbol of its drive toward modernization and economic recovery. The inauguration of this emblem of the culture of spectacle was preceded by the more polemical premières of Barcelona’s National Theater of Catalonia, a work of Ricardo Bofill, and the long awaited renovation of Madrid’s Royal Theater. And the series of débuts wrapped up with the auditorium of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, a lyrical seaside fortress which counts as the finest mature work of the Catalan Óscar Tusquets. Autumn also saw the completion of colossal works like Richard Meier’s Getty Center in the hills of Los Angeles; and the denouement of disputed competitions like the one for Barajas Airport, whose winning by the British Richard Rogers (in association with Madrid’s Antonio Lamela) culminates a magical year for the architect of Tony Blair’s New Labour, or for the extension of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where the Japanese Yoshio Taniguchi prevailed over New York-based Bernard Tschumi and the Swiss partners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. But the season closed with the sad news of the death of Félix Candela, a Spanish architect and engineer who left the best of his poetic reinforced concrete work in Mexican exile, a chapter of history which today’s Europe-facing Spain trusts is a thing of the past.