The past was a secular century. The etymological redundancy refers not only to the decline of the sacred in the 20th century; it also underscores its exacerbated temporality. If we live in the century we know ourselves to be outside religious grounds, and thereby cast into the torrential flow of the contemporary. Secular or lay, and therefore redeemed from the twin tutelage of faith and metaphysics, the survivors of this murderous century have learned to accept the disenchantment of the world and the death of God. Dwelling in space as Greeks and existing in time as Hebrews, we have built a technical civilization that has urbanized the planet and provided the means to de-urbanize it. With this victory and defeat of the spirit, the mutation of churches into identity traits of geographic or ethnic communities has reduced religion to a weapon of the civilizations clash – as the recomposition of the atlas of the empire is called in these skeptical and cynical times – and worship to a tradition of the lower classes.

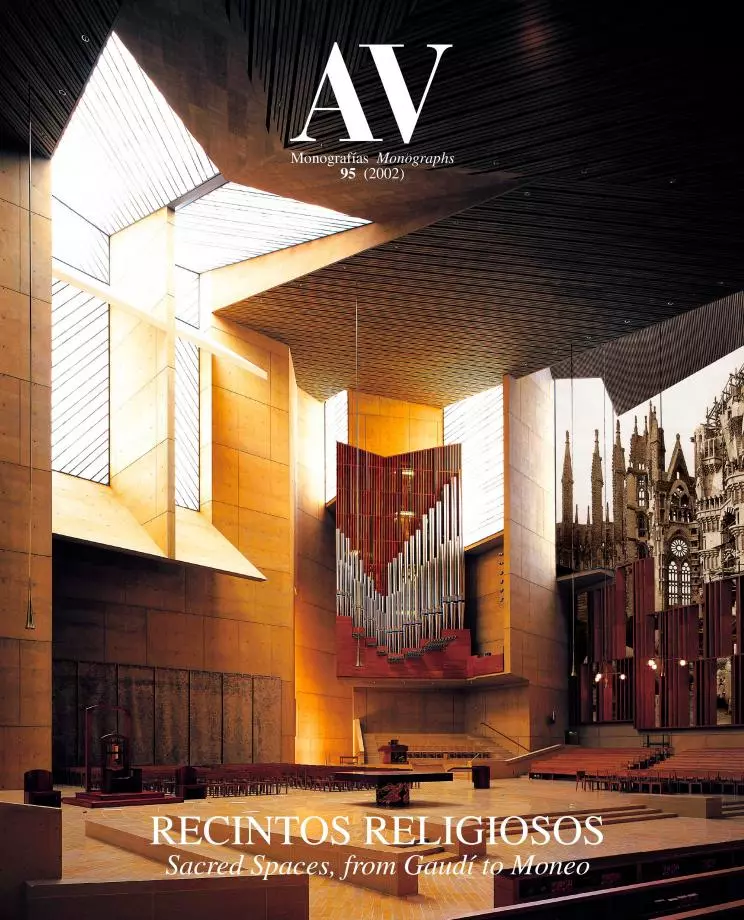

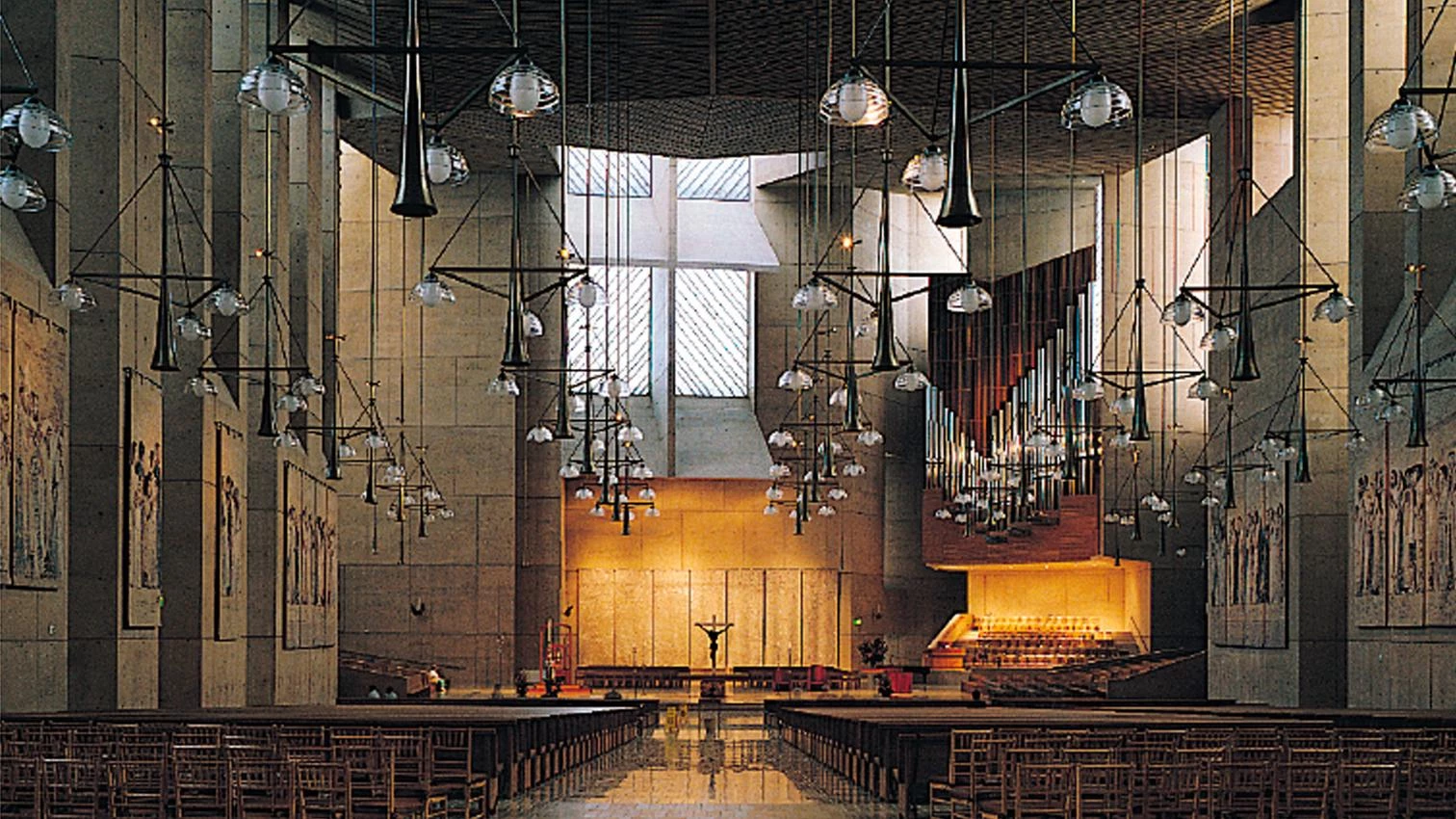

Between the withdrawn piety of the Gaudí secluded in his workshop at Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia and the cosmopolitan agnosticism of the Moneo who builds the concrete folds of the Los Angeles Cathedral there is a century of sacred spaces better described by the history of architecture than by the history of religions, and fed with spiritual energy more for their connection to an aesthetic doctrine than for their fitting a liturgical choreography. Christian mostly – since it is within this cultural sphere where secular modernity emerged – these temples and cemeteries compose a landscape of reluctant fragments that contradict the militant atheism of some avant-gardes, but also confirm the crisis of religious faith. From Nordic romanticism to southern classicism, and from the laconicism of ascetics to the loquacity of preachers, the forms of cult in the past century turned into a cult of forms, celebrating the rite without ritual of artistic truth.

In its last stretch, religious architecture explodes in heteroclite splinters that extend from the colossal churches provided for the spectacle of the masses to the anonymous multi-denominational chapels of airports, from signature construction to amateur theology, and from artistic installations to minimalist landscapes. Imago mundi of a secular world, divine body of a skeptical god, and mystical precinct of a trivial mystery, this sacred architecture believes only in the deliberate worship of space, in the meticulous discipline of matter and in the demanding religion of detail. Exquisite and perhaps dispensable, its episodic works present themselves as sanctuaries of their own perfection; but the violent quiver of faith already lives in other tabernacles, in the Koranic madrasas of unanimous mosques or in the political pedagogy of holocaust museums. Inhabitants of a lay continent, neighbors of Islamic theocracies and subject to transatlantic Christian fundamentalism, Europeans enter the 21st century without knowing if the spirituality claimed for it by Malraux will be finally luminous or homicidal.