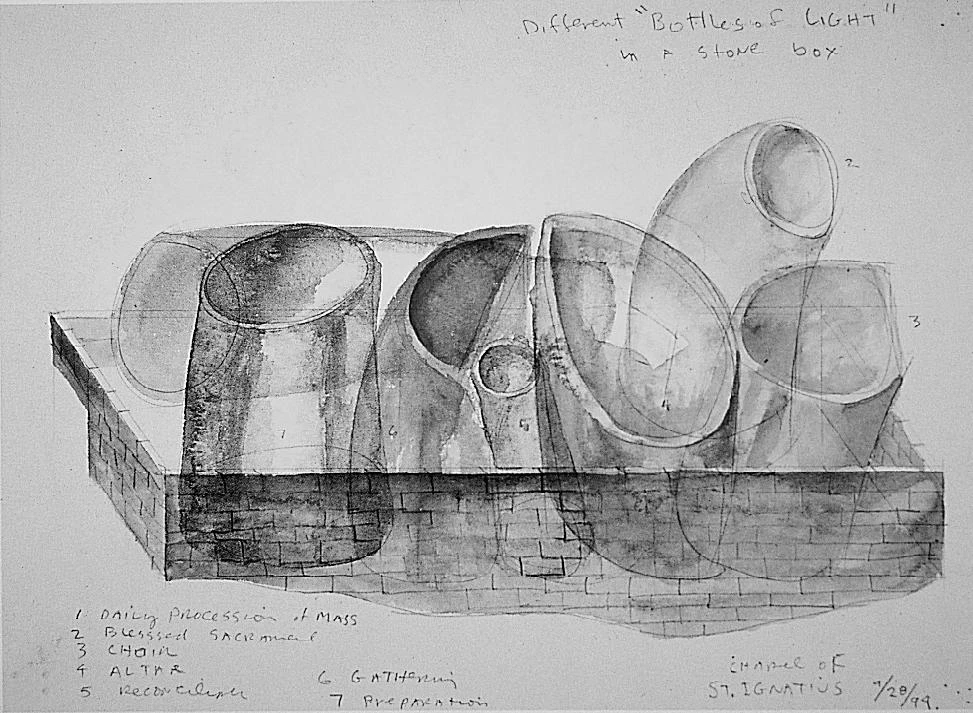

The bottle-skylights devised by Steven Holl reinforce their presence in the chapel of Saint Ignatius, on the Campus of the University of Seattle, with chromatic effects which make it a small liturgical theater.

Religion belongs to our times. The old distinction between divine eternity and secular temporality vanishes when religion transforms into politics and cult into spectacle. In the contemporary world, private faith has become public, and Church is confused with State in an amalgam that is censured as much by the defenders of the sacred mystery as by the champions of civilian reason. But today’s global gusto for spectacle makes the divine and the human pulsate together in the scenographic precincts of modern piety. A small Jesuit chapel in the Pacific and a large Franciscan church in the Adriatic illustrate the theatrical nature of the latest generation of sacred spaces.

Seattle is the city of Bill Gates, but also of Frank Black: the genial owner of Microsoft and the tormented star of the Millennium series make up the at once luminous and somber face of a turn of century marked by the coexistence of high technology and high superstition, the amiable magic of micro-electronics and the ominous fascination of mystery. Technology seems to outmatch mystery at the Je-suit-run University of Seattle, and its rector perhaps meant to compensate for this by putting up a chapel on campus. After inviting several architects to lecture, Father Sullivan gave the commission to the one who had attracted the largest audience: Steven Holl, a young Seattle-born talent based in New York for whom this church is the first major work within the United States.

The result is as entertaining, as theatrical and as rich in effects as one would expect from its author. A concrete box perforated by slits is crowned by six ‘bottles’ capped by glass sheets of different colors. These bathe the interior space with spectral, indirect lights and shine in the night like fairground lanterns: yellows, fuchsias, oranges, blues and greens. The light plaster walls inside the chapel, cut and hung like background sceneries of an avant-garde ballet, and the colored light that slides over the capricious vaults and through the fissures of the perimeter walls make the interior resemble a school play, with the charming daring of an amateur stage-hand and the excessive zeal of a young technician manipulating the colored spotlights. Combining the neoplastic geometries of his Japanese dwellings with the chromatic luminescences of his New York office renovation, Holl’s building in Seattle is a small liturgical theater that is closer to the lively studio of a local television than to the enigmatic spaces of David Lynch, Millennium or Seven.

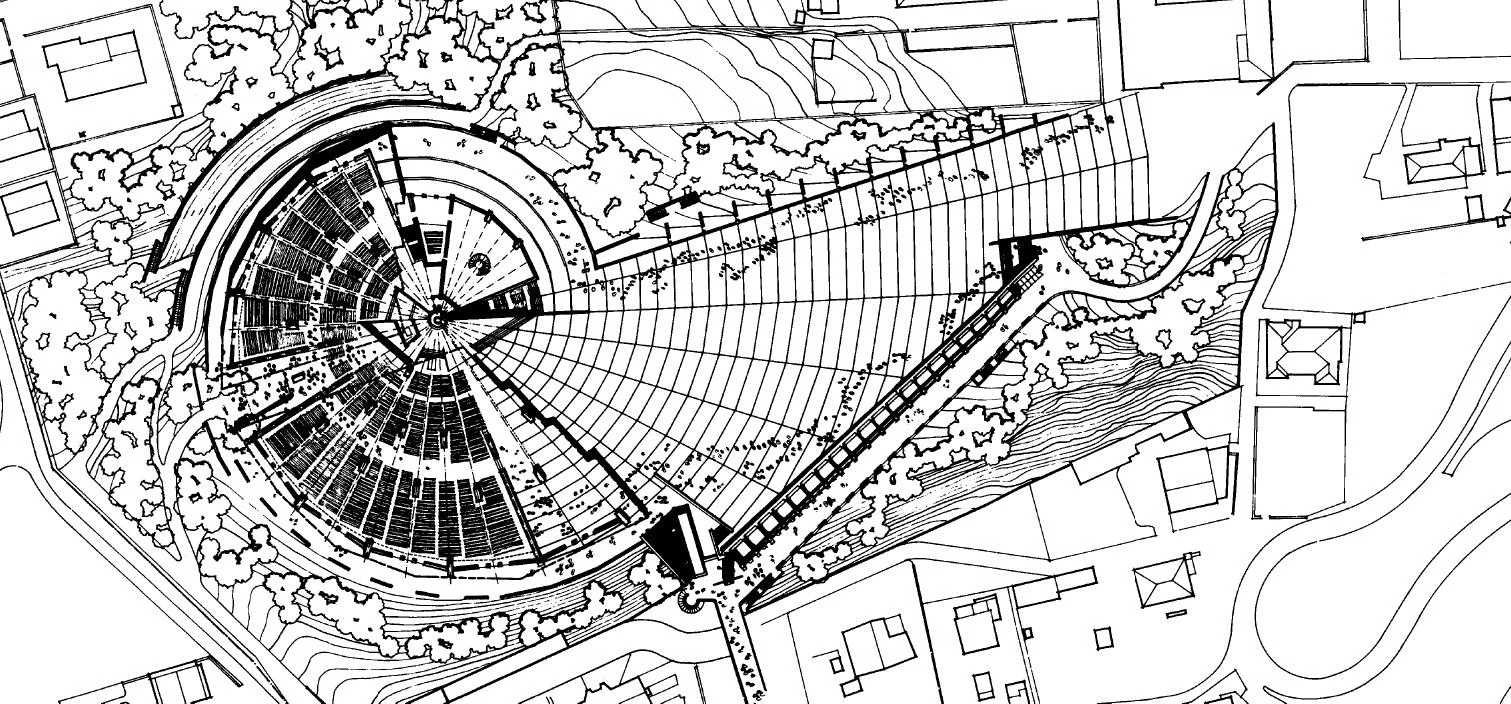

Closer to a concert arena than a temple, the church designed by Renzo Piano is able to hold up to 30,000 of the devotees of Padre Pío that make the pilgrimmage to the Capuchin monastery of San Giovanni in Rotondo.

On the other side of the world, and for a church widely different in scale and nature, the Genoese Renzo Piano has likewise resorted to architectures of spectacle. In this case, however, the need to accommodate large crowds led the architect toward large fair pavilions and rock concert arenas. Thousands flock each year to San Giovanni Rotondo in southeast Italy, lured by the legendary figure of Padre Pío, a Capuchin monk whose stigmas, prophesies and miracles made his convent a pilgrimage shrine even before his death in 1968. John XXIII led those who thought the pious friar short of “a few rosary beads,” but John Paul II was a great supporter of Padre Pío, who predicted his election as pope back in 1947, and to whose prayers he attributes the deliverance from cancer of his friend and adviser, the Polish doctoress Wanda Poltawska.

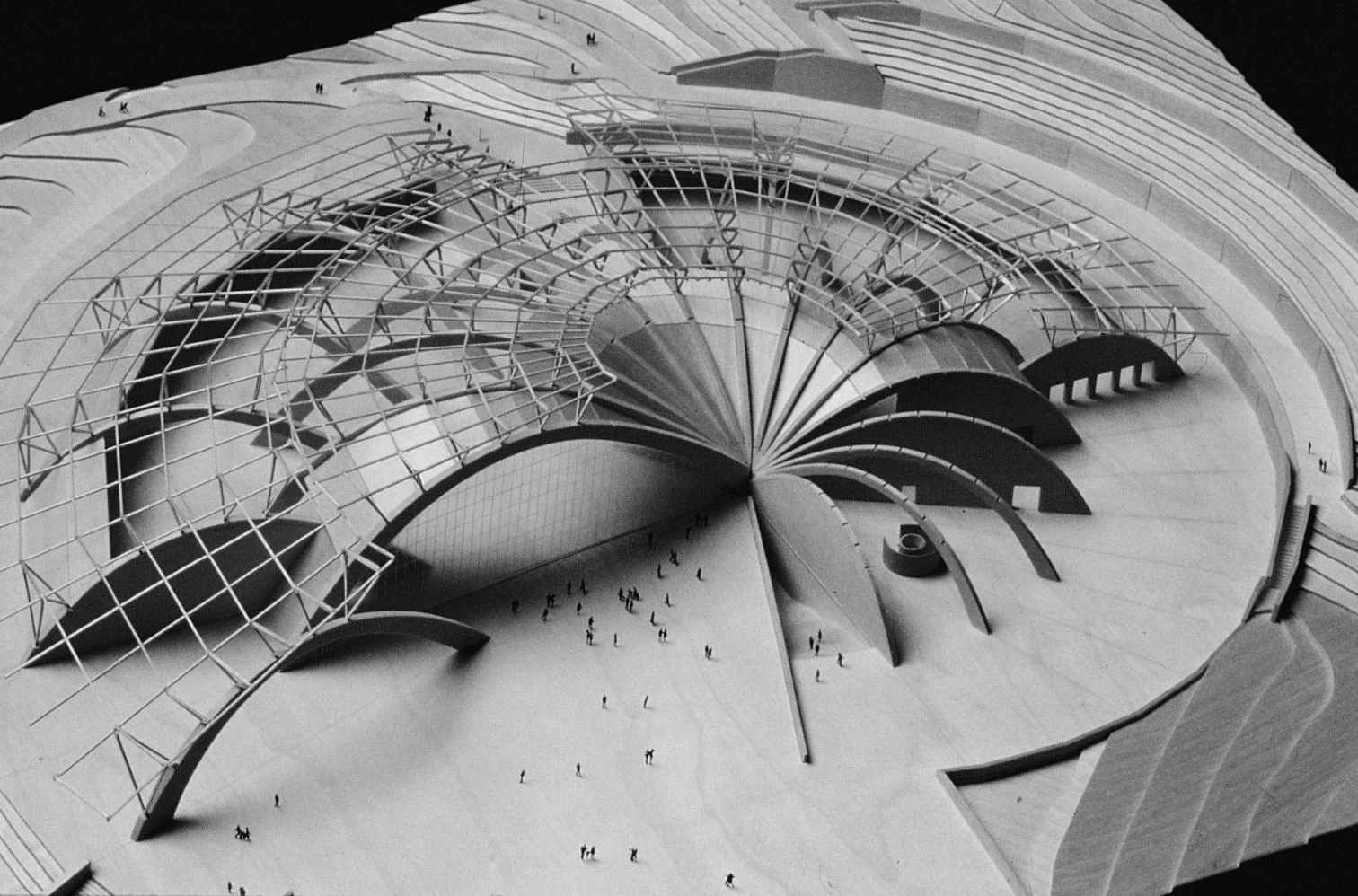

The expected beatification of Padre Pío served as a pretext for the construction of a colossal church with a capacity for 30,000 pilgrims, which Piano designed as a huge space with a spiral directrix, its floor plan opening up like a snail’s shell as the number of devotees grows. Such representation of increasing crowds is achieved through radial arches built with laser-cut, steel-secured ashlar stones and spanning as far as 50 meters: a technical feat that endeavors to be “evocative of the spirit of Brunelleschi,” the Renaissance architect responsible for the dome of the Florence cathedral. Designed by the late British engineer Peter Rice, these extravagant arches – similar to those he contrived with Oriol Bohigas for Seville Expo’s Pavilion of the Future – turn this nautilus-shaped rockodrome into a panoptic fan whose segments guide the eye toward a scenographic hinge, the altar. Still under construction, the church is to be finished by the time the stigmatized Capuchin gets admitted into the company of heaven, joining the busy crowd of holy figures consecrated by the canonizing fervor of the incumbent pontiff, whose total of 270 saints far exceeds the previous record, Pius XII’s 33.

Religion as spectacle incites a fervour for facsimiles. Reproductions of Saint Peter’s of Rome on the Ivory Coast, and of a Uruguayan church by Eladio Dieste in the province of Madrid.

Such figures, which stretch the range of both subjects and objects of worship, as well as the dimensions of its spaces, undoubtedly nurture the spectacularity of contemporary faith. The small chapel of Seattle’s campus, however, shows that liturgy can be scenographic without being colossal – as is well known, Borromini’s San Carlino would fit into one of the pillars of St. Peter’s. But the civil aspect of the new generation of temples is manifested not so much in their scale as in their structure: both the Franciscan church and the Jesuit chapel, and for that matter the majority of today’s religious buildings, are characterized by an arbitrary fragmentation of forms more in line with the ambiguous plurality of secular society than with the theological certitudes of dogma. If the processional linearity of the basilica or the circular communion of the centralized temple once represented the clear-cut geometries of faith, nowadays the organic or sculptural collage of intuitive forms portrays the changing landscapes of free will in our secular religion.

Churches and Mosques, Sacred Facsimiles

In the religion of today’s society of spectacle, signature churches go hand in hand with a devotion for facsimiles. If statues in city parks are being replaced by replicas and monuments are duplicated in theme parks, perhaps we should not be scandalized when a visionary decides to give the forest of the Ivory Coast a reproduction of St. Peter’s in Rome, nor need we evince more than a smile when Madrid’s bishops proceed to build three facsimiles of Uruguayan churches. In the final analysis, forms engender forms, and mimesis is the key to reproduction. Mass production requires a set type, which is why the 3,000 churches built in Poland in the past decade have so many common features. Although fewer, to be sure, than the 1,500 mosques being erected in laic Turkey year after year, and which are docilely molded to the traditional pattern, no matter how earnestly Atatürk’s successors – still snubbed by the exclusive Christian club of the European Union – continue their modernizing crusade against veils and beards. But it is this same archaic tenacity of faith, particularly vigorous along an arch of crisis that stretches from the Afghanistan of Talibans to fundamentalist Algeria, that moves an opportunistic Saddam Hussein to build in Bagdad the world’s largest mosque – its capacity for 45,000 devotees outdoing the Moroccan one inaugurated two years ago by Hassan II – or Fidel Castro to take part in the pope’s Cuban tour as enthusiastically as Bob Dylan in his concert in front of John Paul II. On the lighted stage of the media, the immobile time of faith transubstantiates into the ephemeral time of the century.