Water dilutes the certitudes of architecture. Its liquid state erodes physical foundations and disintegrates the discipline’s conceptual base. Marx warned that under capitalism ‘all that is solid melts into air,’ and Marshall Berman picked up the baton a century later to expose the paradoxes of modernity, which Zygmunt Bauman said could only be liquid. In Spain, Antonio Muñoz Molina with Todo lo que era sólido in 2013 and Alberto Royo with La sociedad gaseosa in 2017 have metaphorically used the states of matter to express their disgust with a modernity which, lacking stable anchors, throws us into the turbulent current of events. In contrast with these nostalgias for solidity, a car ad popularized in 2007 a Bruce Lee line that joins love of movement with the Eastern wisdom of liquid adaptability: ‘Be water, my friend.’

Canonical architecture refuses to be liquid, let alone gaseous. It is aware of water’s importance in urban life as a support of trade routes, and of its aesthetic significance in the works for which it serves as an extensive liquid podium; but it has also learned to fear water’s proximity as a vehicle of hostile incursions or a setting of nature’s uncontrollable forces. For some time now we have been gaining back old port or industrial docks for culture and leisure: cities that, in the absence of a resort tradition, turned their backs on the sea now face it; nevertheless, the catastrophes wrought on coasts are periodical reminders of the permanent danger of water. And while all buildings aspire to permanence, their formal strategies for expressing their times can be solid, liquid, or gaseous, as the three works featured here perhaps show.

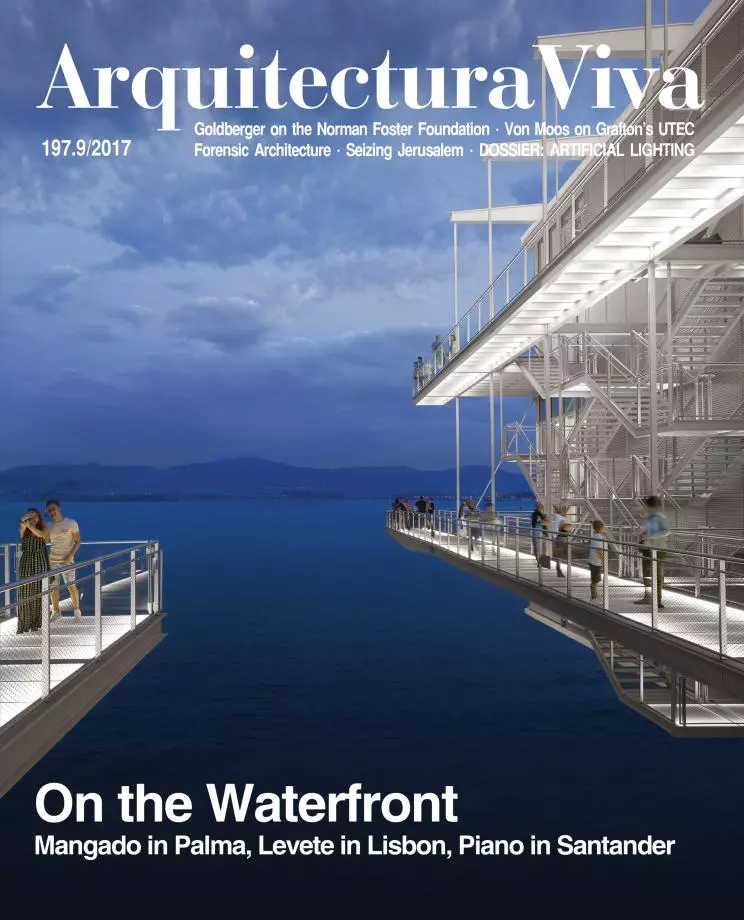

In Palma de Mallorca, Francisco Mangado’s Auditorium and Convention Center confronts the Mediterranean with a folded facade that extends the defensive profile of the city wall, stressing its solidity with rough panels of aluminum foam. In Lisbon, Amanda Levete’s MAAT faces the estuary where the Tagus meets the Atlantic with a topography of semihexagonal ceramic pieces that sparkle like water, shaping with its liquid forms a built landscape that offers itself to the city and strollers. And in Santander, Renzo Piano’s Botín Centre lifts itself off the ground and splits into two lobes clad with mother-of-pearl discs that float, light and gaseous, before the Cantabrian bay, hiding from the city behind foliage but allowing framed views of the sea. Above in Palma, below in Lisbon, before, behind, between in Santander: three seas, three declarations of love for water.