Renzo Piano, who tried to demystify art with the Pompidou Center, ended up building museums for the collections of De Menil in Houston and Beyeler in Basel.

By honoring Renzo Piano, the Pritzker jury has violated an unwritten rule. Only architects given to art or discourse could until now aspire to the award, to the tacit exclusion of those with engineering or technological inclinations. Up to this twentieth edition, Pritzker winners exhibited either an eminently artistic dimension, such as Frank Gehry or Álvaro Siza; a predominantly theoretical vocation, like Aldo Rossi or Robert Venturi; or both things at once, as in the case of our Rafael Moneo. None of these could ever be accused of an excessive connivance with the engineering world. The decision to give the prize to the Genoese architect breaks this absurd and obsolete taboo, generously broadening the horizons of the Pritzker and significantly reinforcing its legitimacy.

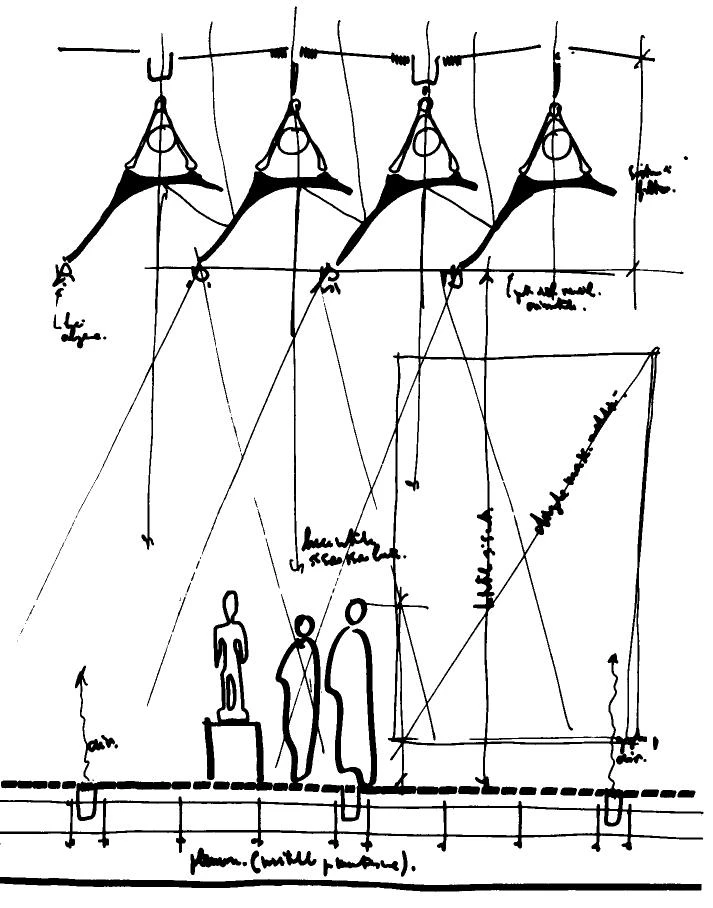

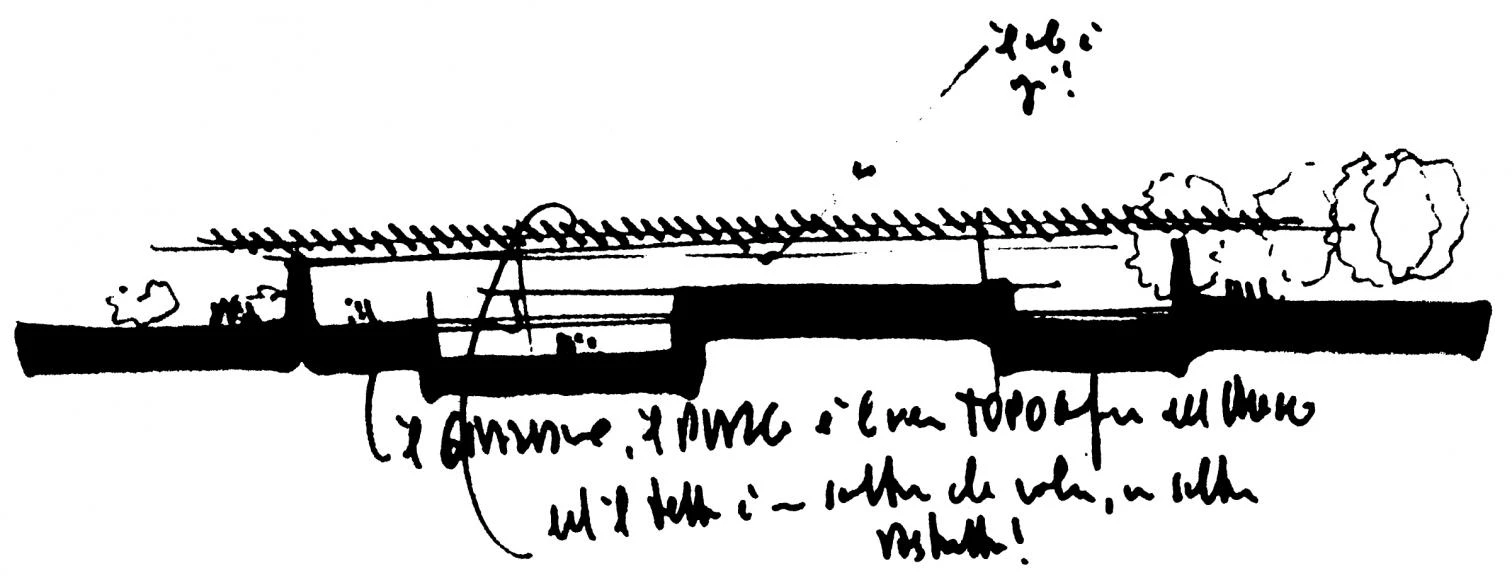

Renzo Piano is, indeed, a builder with an inventive disposition and a populistic sensibility, many of whose ideas have come from ship design and natural organisms, from shells to skeletons; his long-time collaboration with the late British engineer Peter Rice yielded some of the most radically original buildings of the past decades; and his apparent disdain for the visual arts has given rise to several of the most dazzling artistic forms to be found in contemporary architecture, from the lyrical concrete flower of Bari’s soccer stadium, in his native Italy, to the colossal metal wave of Kansai Airport, in the Japanese bay of Osaka.

Together with his then partner the British architect, Richard Rogers, Piano started his career by trying to demystify art through the huge urban refinery of the Pompidou Center in the Beaubourg quarter of Paris. Paradoxically, this same architect was to end up a favorite of the world’s most exigent art collectors, from the recently demised Dominique de Menil, for whom he built a luminous, mutely and refinedly monumental museum in Houston, to the gallery owner Ernst Beyeler, for whose exquisite collection he has recently finished in Basel a sober and silent building with glazed roofs and parallel walls of rough porphyry.

Without renouncing the counter-cultural and ecological convictions of his youth, this relaxed, bearded and casually dressed builder has placed his nautical and organic talents at the service of the art of his times. By endorsing him, the jury of the Pritzker distinguishes the technical imagination and constructional skill, but also the choral anonymity of an architecture that rejects narcissistic protagonism. With this year’s decision, the Pritzker Prize is all the more worthy of its deserved reputation as the ‘architectural Nobel’.