Oasis, fortress and camp, the Tuwaiq Palace in Riyadh, recreation club for the diplomatic area of the Saudi capital, illustrates at once the formal fascination with context and the drama of historic fractures.

Aspecter haunts the West: the specter of Islam. As with the communism of Marx’s manifesto a century and a half ago, nowadays the Muslim religion is the automatic scapegoat for any unexplained act of terrorism. The collapse of the communist enemy after the fall of the Berlin Wall left a void in the collective imagination of westerners, which was replaced by Islamic fundamentalism. In August the United States launched missiles on Afghanistan and Sudan in retaliation for assaults on its embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, and the placid acquiescence of its European allies can only be explained by a deep-rooted conviction in Islamic guilt: from the atrocious massacres of Algeria to the archaic theocracy of the Talibans, the Muslim world appears in the dark mirror of the western media as a cruel catastrophe whose convulsions are a sinister threat to all.

Such a calamitous coverage of Islam obscures and marginalizes the intellectual and artistic production of a group of nations accounting for a billion people. Though sequestered at times by jealous Arabists, misunderstood on other occasions by an impermeable cosmopolitanism, and on the whole ignored by the great forums of international debate, Islamic culture is a vast albeit occult continent, one not deprived of contemporary architecture – practically unknown of outside its geographical limits –and which includes Spain, whose language, architecture and mixed race identity owes so much to eight centuries of Muslim presence. Amid such lazy ignorance the Aga Kahn architectural awards, granted every three years to buildings carried out in the different Islamic countries or for use by Muslim communities elsewhere, constitute a rare and luminous showcase for a landscape immersed in shade, and the holding of the seventh edition ceremony in the Andalusian Alhambra of Granada invites reflection.

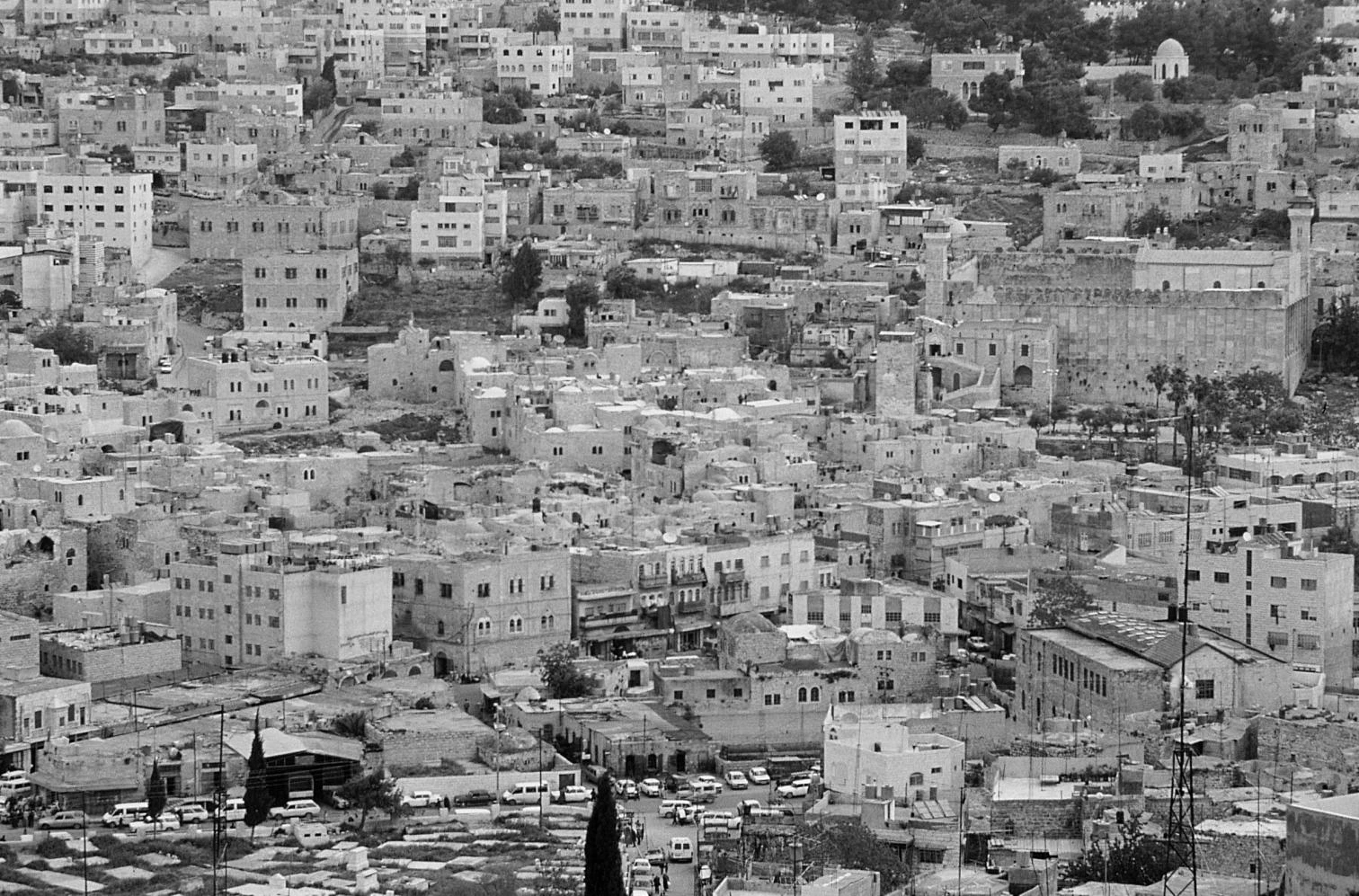

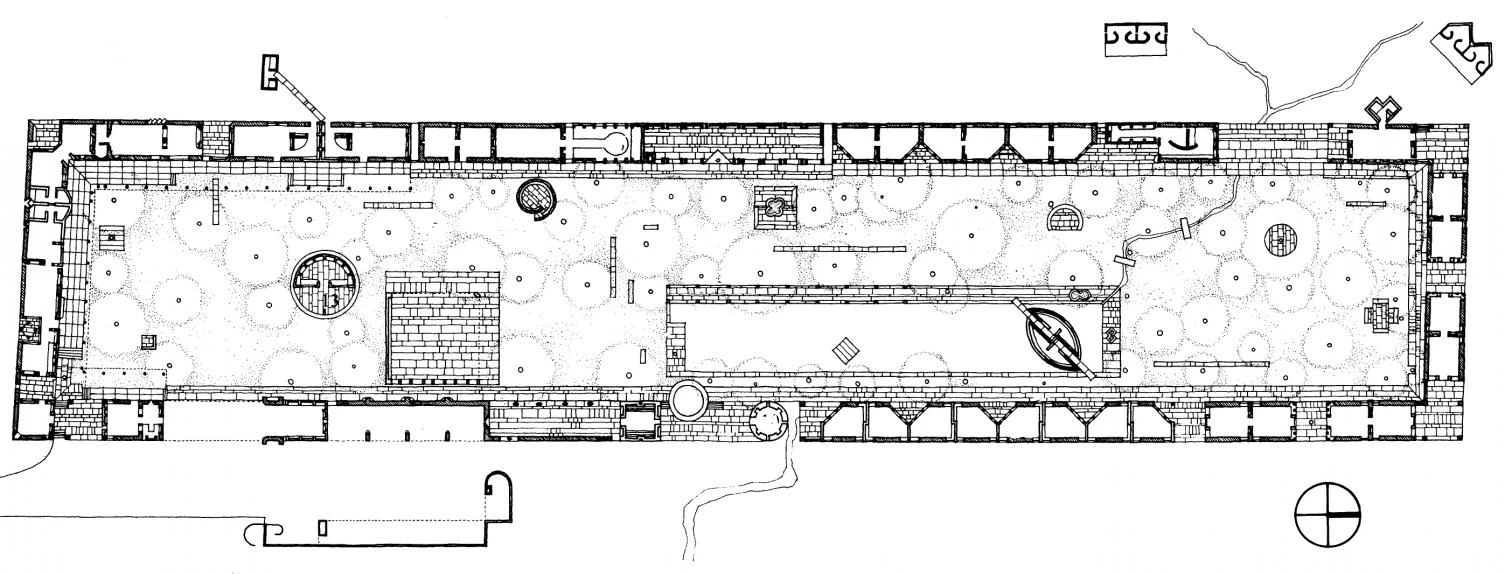

The Aga Khan prizes are interested in social and patrimonial aspects of architecture. Urbanization of poor neighborhoods in Indora; renovation of the old city of Hebron.

Worth US$500,000 and decided on by a jury that on this occasion included the London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid, the Japanese Arata Isozaki and the American philosopher Fredric Jameson, along with several other Islamic architects and historians, the 1998 prize has gone to seven projects whose variety and geographical dispersion reflect the diversity of Muslim societies as much as the direness of their needs and the extent of their conflicts. Ranging from representative buildings like the State Assembly of Madhya Pradesh, the Alhamra Art Complex in Lahore and the Tuwaiq Palace in Riyadh to small realizations like a house on an old rubber plantation in Malaysia and a hospital for lepers in India, and passing through urban planning operations like the refurbishment of the historic quarter of Hebron and the urbanization of the slums of Indore, the recipients offer a polyhedric and plausible portrait of the Islamic world.

The quality of the architectural works honored with the Aga Khan is not always proportional to the magnitude of the investment that has gone into them. Nevertheless, all represent significant aspects of the Muslim world. Nayyar Ali Dada’s rhetorical monumentality in the Art Complex of Lahore evokes the red ramparts of ancient Mongolian forts through trivial geometries that makes one long for Louis Kahn’s Dhaka, and Charles Correa’s flood of formal anecdotes in the Assembly of Madhya Pradesh is hardly controlled by its categorical cylinder-shaped perimeter, but both buildings reflect the cultural and political ambitions of two rival neighbors, Pakistan and India. In contrast, the leprosy center by the young Norwegian architects Jan Olav Jensen and Per Christian Brynildsen is an emotively elemental exercise on building with slate, sandstone and brick vaults, while the urbanization of Indore, designed by engineer Himanshu Parikh, is an admirable endeavor to improve sewer and drinkable water systems with limited resources, technical ingenuity and sociological imagination.

From top to bottom, two images of the sober dignity of the leper colony at Chopda Taluka; the monumental rhetoric of the Arts Complex in Lahore; and the formal anecdotes of the Assembly of Madhya Pradesh.

Opulence and Neglect

Two projects situated in Arabic countries illustrate a formal fascination with context and the drama of historic fracture. The Tuwaiq Palace is a recreational club serving the diplomatic quarter of Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, rising on a stony plateau on the edge of the desert. Designed jointly by the German Frei Otto, the British engineering firm of Buro Happold and the Saudi company Omrania, the club is an 800- meter winding ribbon that contains a garden within, with three large tents attached to its exterior to cover restaurants and swimming pools. At once an oasis, a fortress and a camp, this leisure precinct is a haven of privilege, built in the main by foreigners and reserved for their exclusive use as well. But it is also a testimony of vernacular wisdom and an intelligent tribute to indigenous archetypes, and its distant silhouette of canopies and ramparts evokes both the nomadic nature and the sedentary temptation of desert folk.

The Hebron operation, in turn, aims for the physical and social regeneration of a city held to be sacred by three religions, but which has suffered, in a particularly dramatic way, the consequences of the Arab-Israeli conflict, a conflict which brought about the abandonment and subsequent deterioration or ruin of most of the old quarter’s stone houses. These historic buildings, which contain dwellings on the upper floors and shops at ground level, have been undergoing repair since 1995. A project of the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee, with the participation of the Palestinian administration, the residents and several non-governmental organisations, the aim is to recuperate both the material fabric and the residential and commercial vitality of the old city. But although this choral effort is now starting to bear fruit, one cannot help wondering about the continuity of these achievements, so fragilely dependent as this is upon a peace process that comes to a standstill with every dissent between Arafat and Netanyahu, and upon an economic project that does not seem to offer the cities of Palestine a better future than the deplorable touristic model represented of late by Jericho’s controversial casino.

Between Saudi opulence and Palestine neglect, the varied world of Islam is marked by the coexistence of indulgence and ire, obstinacy and pride, tenacity and fear. In the face of fundamentalist specters – which it is in the interest of so many parties to agitate, overshadowing the true diversity of Muslim societies – the exploration of the material and cultural fundamentals of Islamic architecture that the Aga Khan awards promote is the best possible foundation over which to foster knowledge and dialogue, as well as the best potion with which to ward off the most dangerous of specters: the fanatical specter of mutual ignorance.