The intellectual influence of an engineer father and the Jesuits of Tudela forged the early personality of this native of Navarre who ran the bulls at the San Fermín festival while preparing for admission into the Madrid School of Architecture. There Alejandro de la Sota showed him the abstraction of Mies van der Rohe, but it was the organicism of Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto that he took to, and the young student trained for three years in the studio of Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza. After earning his degree, a year in the Danish studio of Jørn Utzon (then struggling with the construction of the Sydney Opera House) and two in the Spanish Academy in Rome gave his architectural training an unmistakable classical and Scandinavian patina that would soon come in tune with the theoretical influence of Aldo Rossi and Robert Venturi.

Geometry and Type

Here we choose to mark the start of his professional career with three works executed in the 1970s, for together they express Moneo’s inquisitive interest in type and geometry as tools for building the city. The apartment building by the river Urumea, beyond the organic forms of its facade, represented quite a modification of the usual residential type in that area of San Sebastián; the Madrid headquarters of Bankinter, respecting the mansion on the Paseo de la Castellana and raising over it an exquisite facade of smooth brick surfaces, subjected itself to the geometry and material of the preexisting in order to give a lesson of refined contextualism that would be extraordinarily influential in Spain’s architectural culture, to the point of marking a critical turning point in conventional modernity; and Logroño City Hall highlights the institution in the urban fabric with a sharp fracture that is architecturally interpreted through an efficient synthesis of models of the Italian Tendenza and the laconic features of Nordic democracy. The by now Professor Moneo – chair since 1970 at the Barcelona School – tackled each project in a different way, but always with a meditated disciplinary declaration.

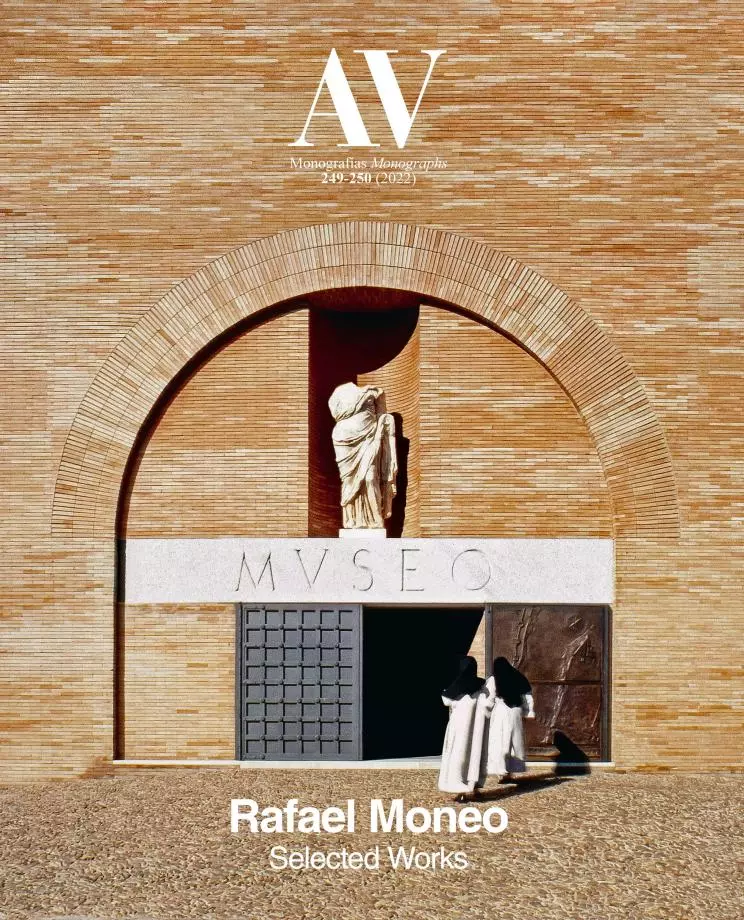

Historical Continuities

In 1980 he was commissioned for what would be his most acclaimed work, the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, but the first half of the 1980s saw him deliver two other projects that sparked a revision of the relationship between history, continuity, and character: the Previsión Española offices in Sevilla and Atocha Station in Madrid. Mérida is without a doubt a fortunate work, one where the difficult challenge of building on invaluable archaeological remains is met with unexpected ease, and where evocation of the imposing scale of Roman architecture is done with the rhythmic regularity and ascetic details of an industrial shed, at once refined and bold, cultivated and popular; the Sevillian Previsión, by the river Guadalquivir and the Golden Tower, is inserted in the city’s romantic veduta with picturesque sensitivity and exquisite materials, respecting the character of the place through a building that is more palatial than financial, more timeless than historicist; and Atocha enlarges the canopy of the old station with a colossal hypostyle hall, in addition creating a new square flanked by the station building, a campanile of Nordic echoes, and a cylindrical volume delimited by robust ceramic pillars. While all these works were under construction, Moneo, who had already taught in the United States in 1976-77 and 1982, received an offer he could not refuse: the Harvard post that had once been held by European architects of the caliber of Gropius or Sert, and from 1985 to 1990 – living in Cambridge with his family – he was Chairman of Architecture at the GSD.

Interpretation and Invention

During the Harvard years, while Spain prepared for the festivities of 1992, Moneo embarked on several projects that combined interpretation and invention in different doses, and were completed around Spain’s annus mirabilis: the Pilar and Joan Miró Foundation in Palma de Mallorca, where he followed the footsteps of the same Sert who had preceded him at the GSD, and which he enlarged with the star-shaped geometries of Mediterranean fortresses and the amber light of alabaster facades; L’Illa Diagonal building, a large-scale real estate project carried out with Manuel Solà-Morales on three blocks of Barcelona’s Eixample, whose mixed program of offices, apartments, a hotel, and a shopping center is undertaken with a single opening repeated on the interminable granite facade, exfoliated at the extremes to avoid monotony; and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, accommodated in a neoclassical palace on Madrid’s Paseo del Prado, which Moneo reinterpreted by inverting the entrance, forming a large foyer and giving the galleries in enfilade a series of lantern-skylights that he would subsequently use in other museums, from Stockholm to Houston. The architect – who had been present in Olympic Barcelona through two buildings under construction (L’Illa and L’Auditori) and in Expo Seville with San Pablo Airport, inspired by the Mosque of Córdoba, just like the enlargement of Atocha for the high-speed train to Seville – returned to Madrid on the eve of its turn as European Culture Capital, which would leave the purchase of the Thyssen Collection as the most enduring fruit of an unrepeatable year.

Geography of the Landscape

Rafael Moneo had in 1989 started work on the small and refined Davis Museum at Wellesley College, and would in 1992 begin the huge compact volume of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston – his first American works, two cubes topped with skylights at the service of art – but in 1990-91 he executed three buildings in Europe which masterfully expressed the tension between respect and rupture when constructing in geographical or urban landscapes: the Kursaal of San Sebastián is an auditorium and convention center that can be described through the metaphor provided by the architect, two rocks stuck on the beach with a crystalline geometry belonging more to the coast than to the grid of the city; the Moderna Museet and Arkitekturmuseet of Stockholm blend into the horizontal, picturesque landscape of their island with almost Scandinavian romanticism, however much the clustering of rooms and the crown of skylights may come from previous projects in Spain; and the extension of Murcia City Hall would face the baroque facade of the cathedral with a petrous altarpiece of defiant abstraction and exact random rhythm, conjuring up an image of memorable musicality.

Art and the Sacred

In 1996 the architect won the Pritzker Prize, and the award ceremony in Los Angeles happily coincided with his appointment to design the city’s Catholic cathedral, a commission of exceptional social and symbolic importance which Moneo executed by combining the visibility from the freeway with liturgical innovations inside, reconciling automobile culture with sacred spaces; no less far-reaching would be the enlargement of the Prado Museum, initiated at the same time, which would complete an extraordinary sequence of works along the Prado-Castellana axis – from Bankinter to Atocha and including the Thyssen Museum and the extension of the Bank of Spain, a project designed in 1978 but completed only in 2006 that shows admirable subordination to the original building – to show that the Moneo of international successes, from the Beirut Souks to the laboratories in Basel or in the universities of Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton, could also be a prophet in his own land; and special meaning can also be gleaned from the Iesu parish church in San Sebastián, a lyrical space built with light and financed by the supermarket housed under it, uniting the sacred with the profane, as in Los Angeles.

The Versatility of the Discipline

In the 21st century, Rafael Moneo has kept up his versatile approach to the discipline, raising cultural buildings – from the Beulas Foundation and the Museum of the Roman Theater of Cartagena to the Deusto University Library and the Museum University of Navarre – but also healthcare facilities like the Maternity and Pediatric Hospital in Madrid, civic works like the Toledo Convention Center, and commercial complexes like the Mercer Hotel and the Puig Tower. And particularly aligned with his sensitivity to the land and to history are the two buildings that close this itinerary, the topographic winery in El Bierzo and the contextual construction at Berlin’s Schinkelplatz, to which we add two projects very much loved by the architect, the Córdoba Congress Center and the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum Extension, where the master of an entire generation demonstrates the rare combination of rigor and freedom that characterizes a career of extraordinary professional and intellectual brilliance, without question the most outstanding trajectory that Spanish architecture has seen in the past half-century, and we are pleased to make it the theme of the monograph with which we round the cape of 250 issues.