Seasons of Transit

The death of the master Sota, Moneo’s Pritzker, the UIA Congress in Barcelona and the Prado competition sum up Spain’s architectural year.

The year of political change-over in Spain has also been one of transits in architecture: the passing away of Alejandro de la Sota, the international consecration of Rafael Moneo, the crystallization of spectacle at the International Union of Architects Congress in Barcelona and the fiasco of the competition for the extension of the Prado Museum in Madrid have in a bittersweet way marked the four seasons of the architectural year.

It is common to sum up a period through a list of buildings, but 1996 is best described by events; on hindsight, no project completed during the year seems as significant as some of the occurrences that befell us. Within the fractured framework of a world that is at once interdependent and egoistic, and in the ambiguous ambit of a country where economic prosperity and political upheaval coexist, Spain’s architectural year is reflected by two personal transits and two institutional ones.

1996 has witnessed the definitive consecration of Rafael Moneo who, along with the Pritzker Prize, also won the Gold Metal of French Architecture, the UIA Medal and the competition to build the Los Angeles Cathedral.

Winter of the Master

The death in February of Alejandro de la Sota, the most respected of Spanish masters, was the close of both a tenacious biography and a luminous chapter of contemporary architecture in the peninsula. A dogged defender of ideas against forms, De la Sota left us a number of essential works, including the Civil Government headquarters of Tarragona and the Maravillas Gymnasium in Madrid, as well as a distrust of style which he elevated to the category of ethics, and which his ‘Sotian’ disciples paradoxically interpreted with the technological minimalist language of his final projects.

But the winter of contemporary architecture also witnessed other transits. François Mitterrand’s demise in January and Felipe González’ electoral defeat in March symbolically marked the end of fifteen years of ‘Mediterranean socialism’ in France and Spain, two countries that during this period efficiently used signature architecture as cultural avant-garde and political propaganda. Between social democracy and social opulence, from the presidential projects in Paris to the Olympic works of Barcelona, architecture and power lived a blissful and fertile romance.

February saw the passing away of Alejandro de la Sota, a defender of ideas as opposed to forms, and architect of such paradigmatic works as the Maravillas Gymnasium in Madrid or the Tarragona Civil Government.

Spring in the Summits

Rafael Moneo won the Pritzker Prize in April, and accepted it in June on the Los Angeles hilltop that is the building site of the Getty Foundation’s new headquarters. But the Brentwood heights where architecture’s unofficial Nobel was awarded were not the only ones to be visited by the Navarrese, who this year also received the Gold Medals of French Architecture and the International Union of Architects, and elegantly wrapped up his streak of international triumphs by beating the Californians Frank Gehry and Thom Mayne in the competition for the Catholic cathedral of Los Angeles.

Significantly, the Pritzker rewarded Moneo for a traditionalist rigor that is diametrically opposed to the figurative avant-gardism of Rem Koolhaas, the Dutchman who is now his colleague at Harvard University and whose monumental manifesto S,M,L,XL has been the year’s most talked about book; an architect, incidentally, whose most important commission this season is also situated in Los Angeles, having been selected in May to design a colossal extension for Universal Studios, which has no qualms about competing with the Disney empire in the fascinating and equivocal field of leisure.

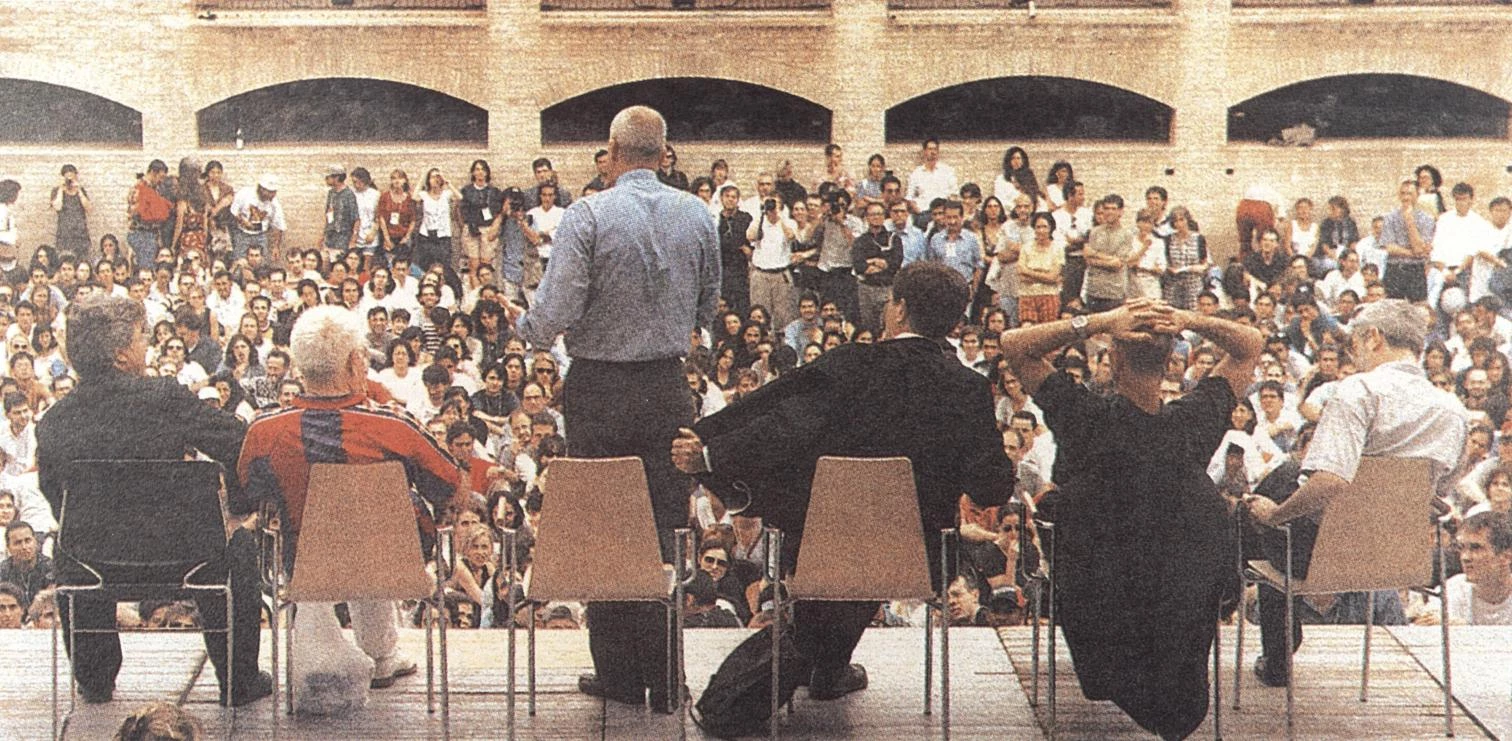

En Barcelona, la masiva asistencia de público transformó el congreso de la Unión Internacional de Arquitectos en un espectáculo mediático, mientras en Madrid el concurso del Museo del Prado quedaba desierto.

Summer and Smoke

The frivolous and friendly mood of summer in Barcelona served as a framework for an architects’ congress that was equidistant between a rock concert and a political rally. Overwhelmed by the multitudinary attendance, the initial session of the chaotic event took place outdoors, in front of Meier’s new museum, and subsequent assemblies were held in the city’s largest covered arena, the Palau Sant Jordi built by Isozaki for the Olympic Games. For three days in July, the spectacle of architecture became a spectacle of architects, feted and hounded like mediatic stars.

Among them, no one as popular as Peter Eisenman, who donning a Fútbol Club Barcelona sweat shirt preached the gospel of the ‘formless’ (perfectly exemplified by his Aronoff Center in Cincinnati, which was completed in August); or as Norman Foster, who had to flee from a swarm of paparazzi that was more interested in his marriage to the Spanish psychologist Elena Ochoa (finally celebrated in September) than in his colossal and painstaking architecture, so admired by Mayor Pasqual Maragall and spread out from the Berlin of ‘new simplicity’ to the Hong Kong of Asia’s vertiginously accelerated Pacific Rim.

Autumn without a Project

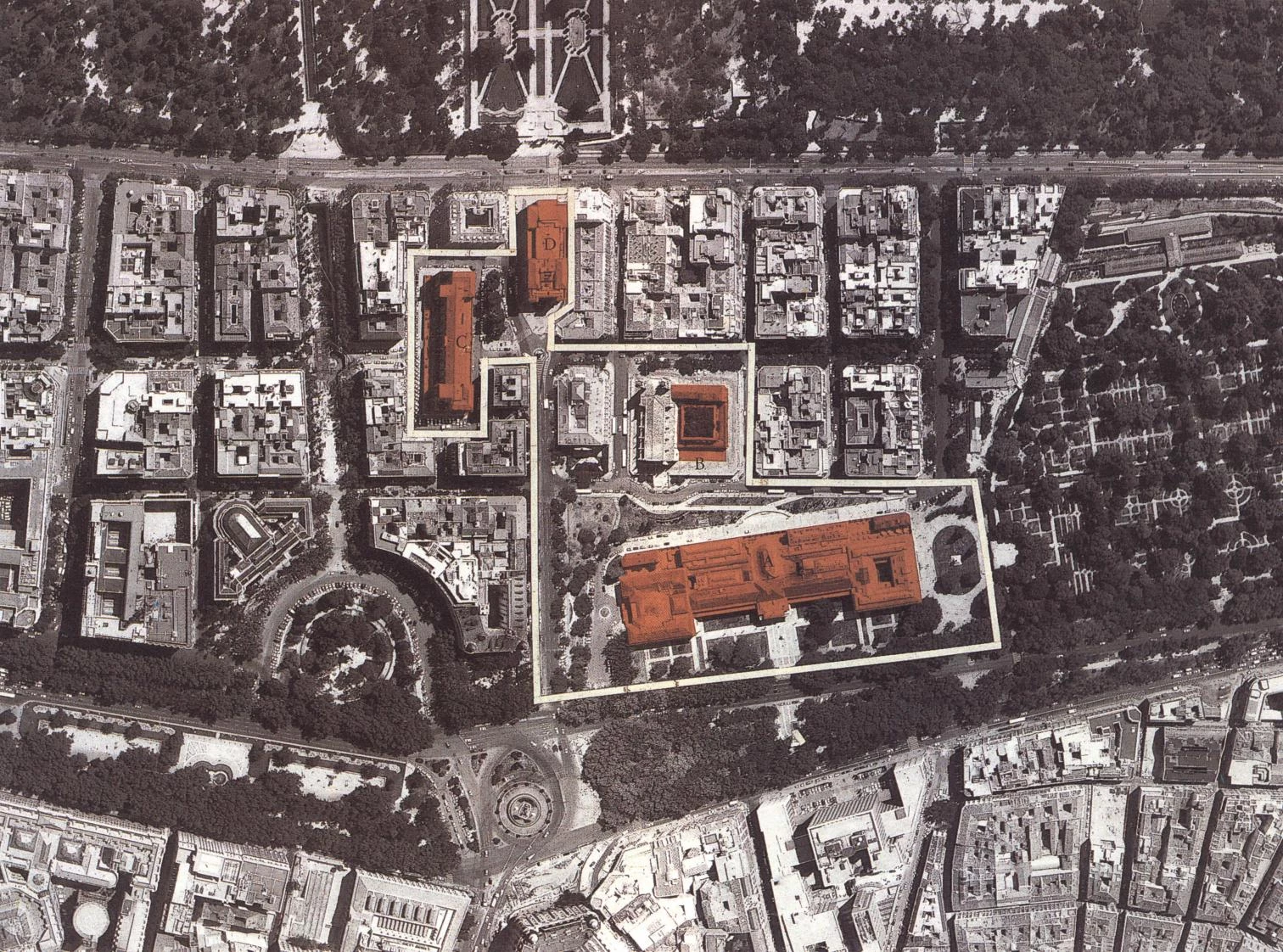

Autumn anticipated its melancholic mood with the decision that left the competition for the extension of the Prado Museum without a winner: yet one more episode in the troubled history of Spain’s leading cultural institution. The October exhibition of the 500 entries exposed the fact that the causes of the fiasco lay in the actual competition guidelines, whose confusion was but a reflection of the drifting course of a museum which the new conservative government hopes to turn into its flagship.

No less a flop was the Biennale di Venezia, which closed its jumbled seismic metaphors in November, after paying tribute to Johnson, Niemeyer and Gardella. Proving more energetic than Venice was Rome, which by Christmas had launched a huge urban regeneration program, with the main pieces to be undertaken by Renzo Piano and its vision already focused – like millennium London – on the fast approaching year 2000.