Turn of the Millenium Vertigos

At the end of the millenium, the swift constructions of transport, sports or commerce exist alongside minimalist precincts of austerity and silence.

The end of a millenium rightly calls for panic. But this will be denied us, for lack of time. To decently enjoy the millenarian terror, it is important to inhabit the planet with a calm and vegetal rhythm that nurtures uncertainties, projects anxieties and imagines phantoms. Yet the reckless speed at which everything moves in these times can only induce vertigo. And nausea, as those who have experienced persistent travel sickness and the abyssmal sensation of helplessness it brings well know, is incompatible with streaks of panic.

Exhibiting a stepped facade to the Diagonal, in Barcelona’s Illa Moneo and Solà-Morales propose a city block with various functions that exploits the visibility offered by its placement and large scale.

The architectures of the year that is ending conspire to convoke vertigo: seaborne airports, quick facades of changing institutions, stations for underwater trains, geometrical aircraft carriers in the midst of highways, movements brought to a stop only to keep everything moving. These are accelerated and colossal architectures at the service of the massive flow of people, objects or images, architectures of transport and symbolic consumption, architectures of communication and change, architectures, finally, of dizzying and global permanent movement.

In Spain, the most notorious buildings have been the most visible: metropolitan and formidable, they owe their popularity to their site and scale, but equally so to the overwhelming formal gesture that cuts a figure in the windshield of the vehicle. Barcelona’s Illa is an enormous stone block for mixed uses built by Moneo and Solà-Morales on the edge of the Diagonal’s busy and swift traffic, a Cubist escarpment leaning on the avenue like a fugitive and fatigued skyscraper; Madrid’s peineta is the meteoric and singular tier of an Olympic stadium erected by the Sevillians Cruz & Ortiz among wastelands and highways, a colossal concrete curl, desolate and fleeting. Voices in the distance, they are signs of transit and of transition.

Its fleeting and distant perception from one of Madrid’s surrounding highways determined the way in which Cruz and Ortiz grouped the stands of the athletics stadium, planned as the focal point of a large area.

If Jacques Attali is right, the coming millenium will begin in the world with two centers of planetary power: the Asian economies of the Pacific Rim, and the North American media. Both can offer significant architectural examples this year. Asia’s entrepreneurial muscle is admirably expressed in the new airport of Kansai, built by the Italian Renzo Piano in the Bay of Osaka on an artificial isle, the world’s largest: an operation of futuristic engineering which has cost the almost unconceivable amount of 2 trillion pesetas. The terminal, which with its 1,700 meters is also the longest existing building, was designed with curved profiles obeying the flows of conditioned air, guided without need for conduits by gigantic concave louvres that give the interior a light, patinated, solemn look. The rising economies of the Pacific have, in this Japanese island airport, a crossroads of air traffic, but also a sign of architectural emulation.

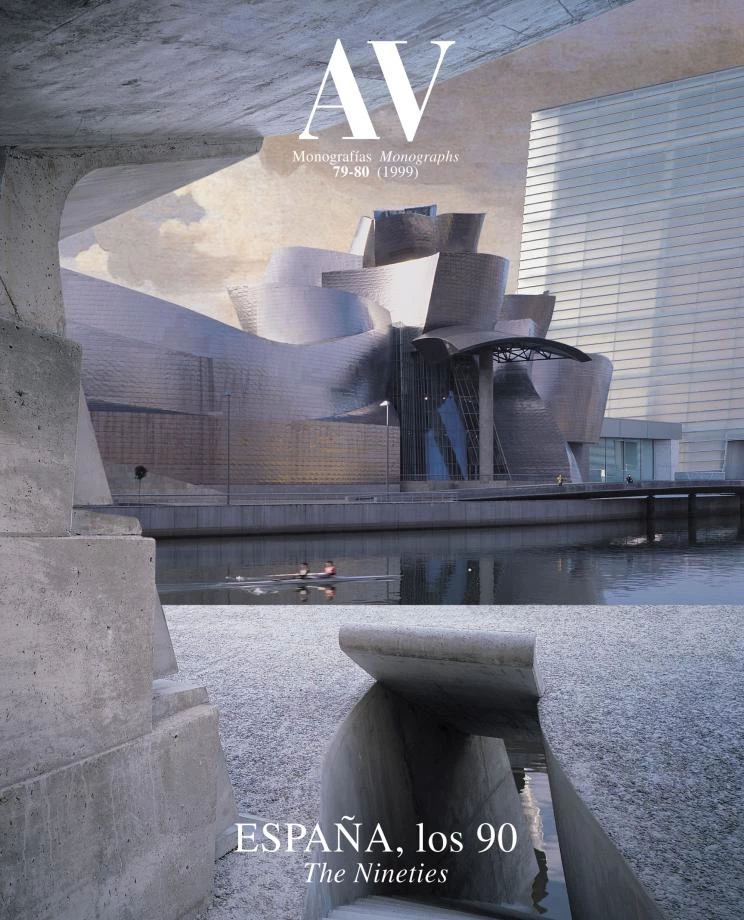

Meantime, the overwhelming influence of American communications is eloquently manifested in the mediatic popularity of the sculptural architecture of the Californian Frank Gehry, who has become a compulsory – and energetically exported – cultural cliché. In Europe, where he had previously built the Eurodisney pavilions, the fish of Barcelona and a showroom for the company Vitra, Gehry this year finished the American Center of Paris and the Basel offices of the same Vitra, besides starting construction work on the colossal Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao and drawing up the project for his first job on the east of the continent: an undulating office building in Prague. Such proliferation of commissions simultaneously bespeaks the tenacious survival of artistic architecture, and the power of the media to project images to a global audience.

The Channel Tunnel, which links the transport node of Lille (with the Congrexpo by Koolhaas, above) and London’s Waterloo Station (a work of Grimshaw, below) expresses the process of European unity.

In this intercommunicated and interdependent planet Europeans are trying to build a life raft of survival and perhaps segregation, made of a network of political and commercial ties but entangling in the failures of governments, incapable even of avoiding wars on home ground. The opening to traffic of the Channel tunnel is so far the best symbol of such will to integrate, though architecturally expressed differently on each end of the railway line.

In London, Waterloo International Station is a huge glass and steel shed designed by Nicholas Grimshaw on traditional lines of British high-tech. In Lille, where trains coming in from Great Britain fork out toward Brussels and Paris, the Dutchman Rem Koolhaas has covered the high-speed station with a surreal agglomeration of enormous and extravagant buildings, emblems of his passion for metropolitan congestion, including his own immense Congrexpo and the ski-boot-shaped tower of the Frenchman Christian de Portzamparc, unexpected winner of the year’s Pritzker Prize.

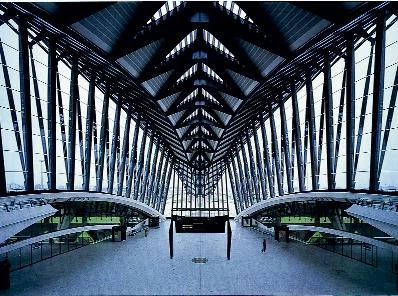

Still in France, Santiago Calatrava completed the Lyon-Satolas Station, connecting the TGV to the airport. It is a rare and Gothic work, at once archaic and futuristic, managing to endow the rapid movement of contemporary transport with an orderly and romantic agitation, very far from the arbitrary juxtapositions, risky fragmentations or the immaterial transparencies through which the evanescent spirit of the times has often liked to express itself, as in the most recent building by the Frenchman Jean Nouvel, the crystalline Cartier Foundation in Paris.

The Spaniard has been less lucky in Berlin, where in the end it was Norman Foster who obtained the commission to remodel the Reichstag, symbol – if ever there was one – of Europe’s tragic history, and emblematic piece of the ongoing reconstruction in the German capital. In this gigantic operation, which has brought the full cast of architectural stars together in the city of the Spree, the usual individual and unique expression of each one has had to engage in dialogue with a cultural climate that has tired of the artistic narcissism of the eighties and demands a ‘new simplicity.’ This return to order, occasionally manifested by buildings of a totalitarian severeness, suits the preferences of the youngest architects, trained as they are in the austere tradition of minimalism. The result is a panorama wherein the accelerated vertigo of contemporary society is countered by stern precincts of order and silence.

Santiago Calatrava houses the hectic transit of travellers between the TGV and airport in Lyon-Satolas Station beneath a glass and steel skeleton that with two curved canopies resembles a bird stopped in flight.

It is hard to tell if minimalist sensibilities can build something more than provisional shelters of resistance to the uncontrollable forces of our century, which untiringly generate vertiginous works. In any case, both autistic quietude and neurotic agitation have healthy and analgesic effects against the pangs of panic. And we probably must not expect any further curative virtues from these disconcerted, end-of-millenium architectures.