If barça is more than a football club, the Liceo is more than an opera house. It was destroyed by fire on January 31, 1994, but the burning soot ignited an institutional consensus that led to an immediate start of reconstruction works. Over the still hot ashes, Jordi Pujol assured Queen Sofía that the Liceo would reopen before Madrid’s Teatro Real (then immersed in an apparently interminable work), and a year later the green light was given to the project of architect-critic Ignasi de Solà-Morales, who had the autumn of 1997 as a deadline. But the Real managed this date alone, and the Liceo has had to wait out two more seasons to resume the contest between Spain’s two grand lyrical arenas. With a total cost resembling that of Madrid’s (around 15 billion pesetas) but sparking very different emotional echoes, the new Liceo is a plausible gauge of Catalonia’s cultural temperature, as well as a reliable indicator of some symbolic currents of our times.

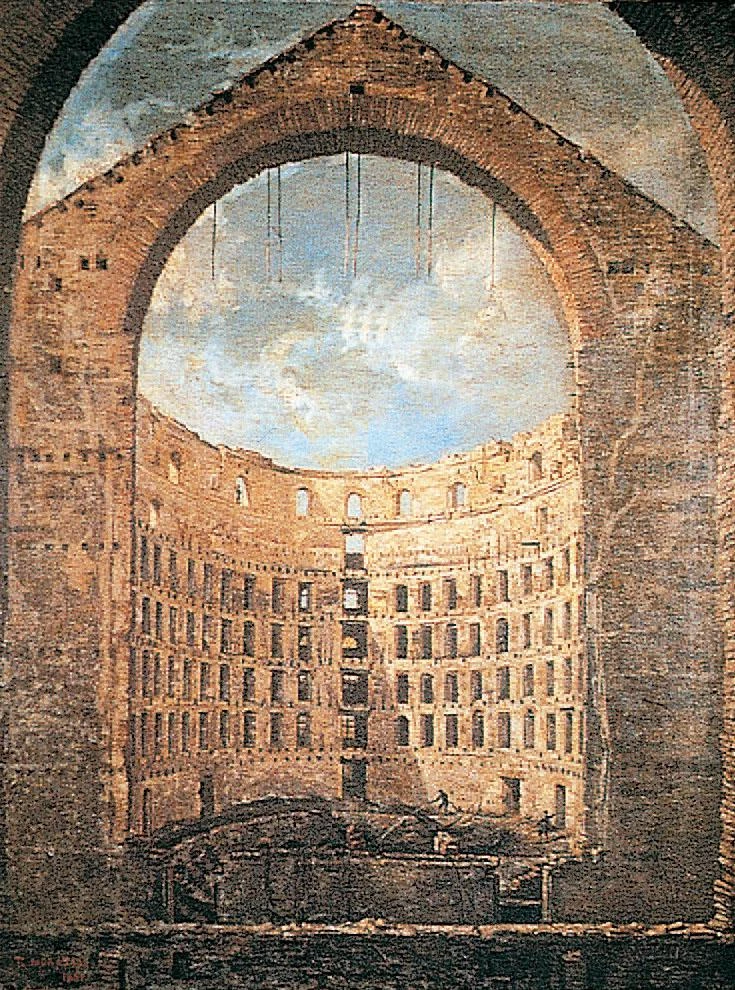

The 1994 fire destroyed the Liceo opera theater, leaving behind only the smoking void of its horseshoe, defined by the perforated wall of the former stage boxes.

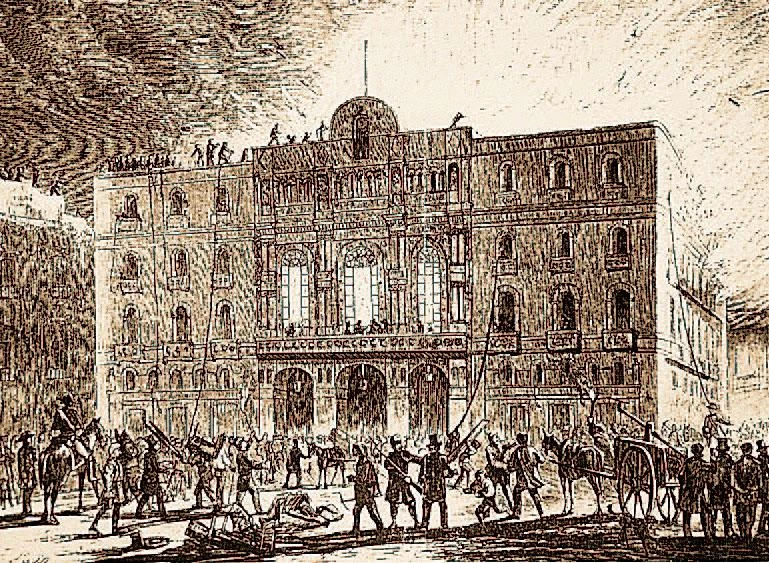

Built in 1847 on the Rambla, over the ruins of a convent and Baroque church that had burned down in 1835 and now fell prey to laws involving the cession of ecclesiastical property, the Liceo patterned after the competition-winning project of architect and academic Miquel Garriga i Roca in turn succumbed to flames in 1861, to be reconstructed with few variations in little more than a year by another architect, Josep Oriol Mestres. Undergoing innumerable alterations in the course of time but no significant modifications in its general structure, this is the building that came down in the 1994 blaze; and that which it was decided, after the emotion-ridden plebiscite of the days following the catastrophe, should be rebuilt in the form of a facsimile on the very same spot. But fire is never altogether in vain. If in 1835 it allowed the bourgeoisie to take the place of the church on the city’s game board, in 1994 it was an instrument through which institutions and large corporations could replace the old bourgeoisie in the colonization of symbolic urban premises.

The Liceo’s latest catastrophe faithfully reproduced the images of its first fire in 1861, reflected in the painting of Moragas, on the previous page, and the engraving depicting the building in flames, on the right.

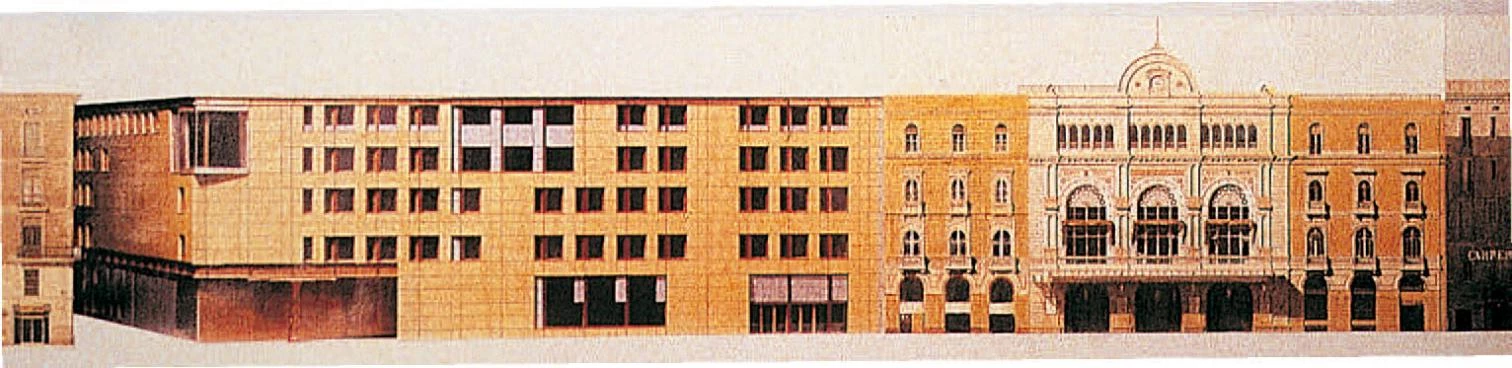

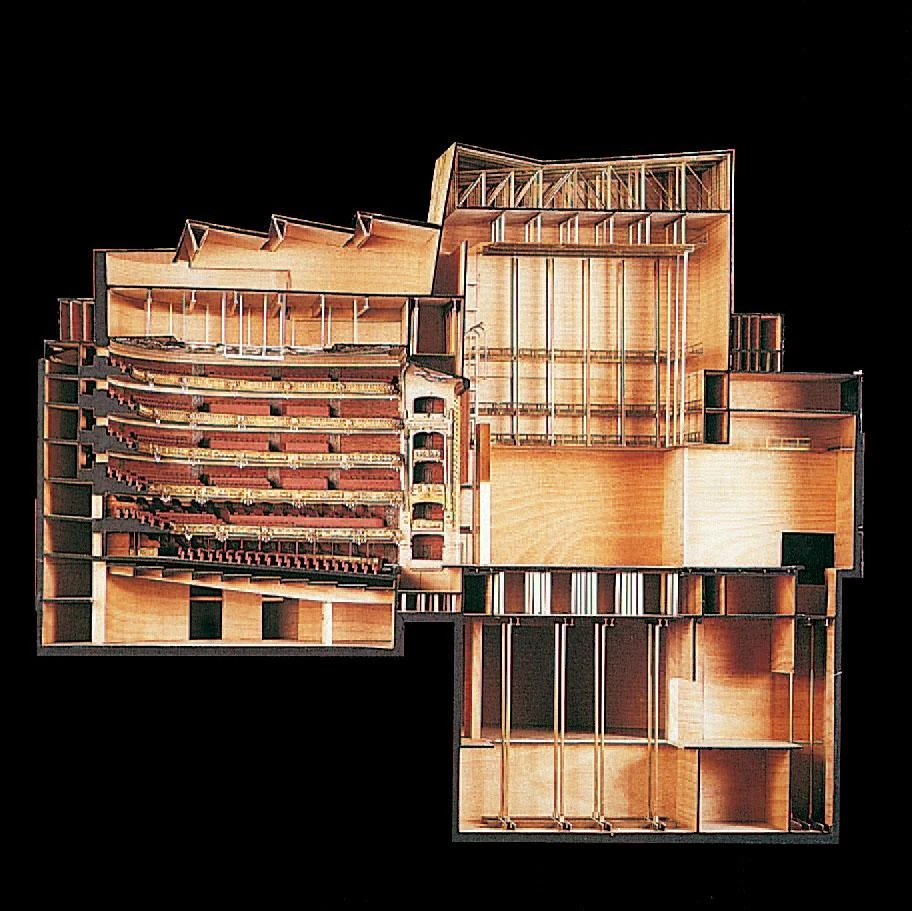

Despite the sentimental fervor in favor of a facsimile, the construction that now rises on the Rambla is markedly different in character and dimensions from the old Liceo. After expropriations costing 3 billion pesetas, the theater has taken up a good part of the adjacent parcels, and has grown upward as well, through a gigantic gridiron tower, and downward in the form of colossal pits. In sum, what was originally 12,000 square meters now measures 32,000. And this bulimic opera house, funded by the generosity of public budgets and the ritual handouts of banks and large firms, has also changed in character, the ostentatious showcase of traditional families in velvet-upholstered boxes giving way to a venue for the new political and economic elites, for whom the opera is a singularly efficient legitimizing mechanism. Like a carriage with an internal combustion engine, this solemn theatrical machine pretends to freeze time in a fixed photograph of splendor and glitter, when actually that cultural species in danger of extinction only survives through artificial respiration. The giant saurian has not been regenerated with the information of its documental DNA; in the Jurassic park of contemporary opera, most organisms are animatrons: mechanical replicas that are fascinating to all.

To all. Indeed, the clamor for facsimile is so unanimous as to inhibit any discrepancy, however motivated. In the case of the Liceo –which, like the barretina hat, the Pica de Estats, the sardana dance or the Virgin of Montserrat, forms part of Catalonian identity – divergence is outright heresy. The commotion caused by the flames had even the normally caustic columnists Maruja Torres or Vázquez Montalbán sequestered in a bout of nostalgia for childhood; while the writer Eduardo Mendoza, who dared to remember the reactionary nature of the Liceo bourgeoisie, to suggest the advisability of a new, less showy building, and to call for a renewal of the genre that would avoid the ‘caricature of papier-mâché props and the trills of a whale,’ eventually admitted, with intimidated timidity, to having taken part in the polemic ‘perhaps with more vehemence than reason.’ In this heated atmosphere, the playwright Albert Boadella was one of few to question the huge budgets of the opera, its exhibitionistic ostentation and its insatiable appetite for technical means, but his efforts to initiate a debate on the financing of the arts hardly bore upon the general mood of exaltation that followed the fire.

The new Liceo lifts its colossal tower of gridirons above the roofs of a very dense and fragmented area in Barcelona’s old quarter, displaying to the Ramblas a new facade of unexpected composition.

A longitudinal section of the project model shows the auditorium above the low, sunken foyer, as well as the stage, which rises out above the theater machinery pit and is crowned with the large volume of gridirons.

And if criticism then was impertinent, it must be even more so in this happy moment when, facing fashion designer Antonio Miró’s curtain and under the oculi of the conceptual artist Perejaume, bel canto lovers and Wagnerians, socialists and nationalists postpone their differences to celebrate, to the opening bars of Turandot, the operatic phoenix’s resurrection from its ominous ashes. Some architects will deplore the project’s having been commissioned without the blessing of a competition, in contrast to the parallel case of Venice’s La Fenice, which burned down two years later and for whose reconstruction Gae Aulenti had to contend with Rossi, Valle, Aymonino and Gardella. Others will comment on the poor volumetry of the gridirons, the unhappy composition of the new facades or the contrived section of the added foyer. A few, finally, will whisper the loudly known secret that the intellectual quality of a historian is no guarantee of esthetic achievement. But no one will express these judgments in public, for fear of being dismissed as envious, a killjoy or unpatriotic in the plebiscitary climate of consensus that the Liceo imposes on Catalonia. And what right has a Madrid-based Aragonese to say what his Catalan colleagues prefer not to? Felix fenix.

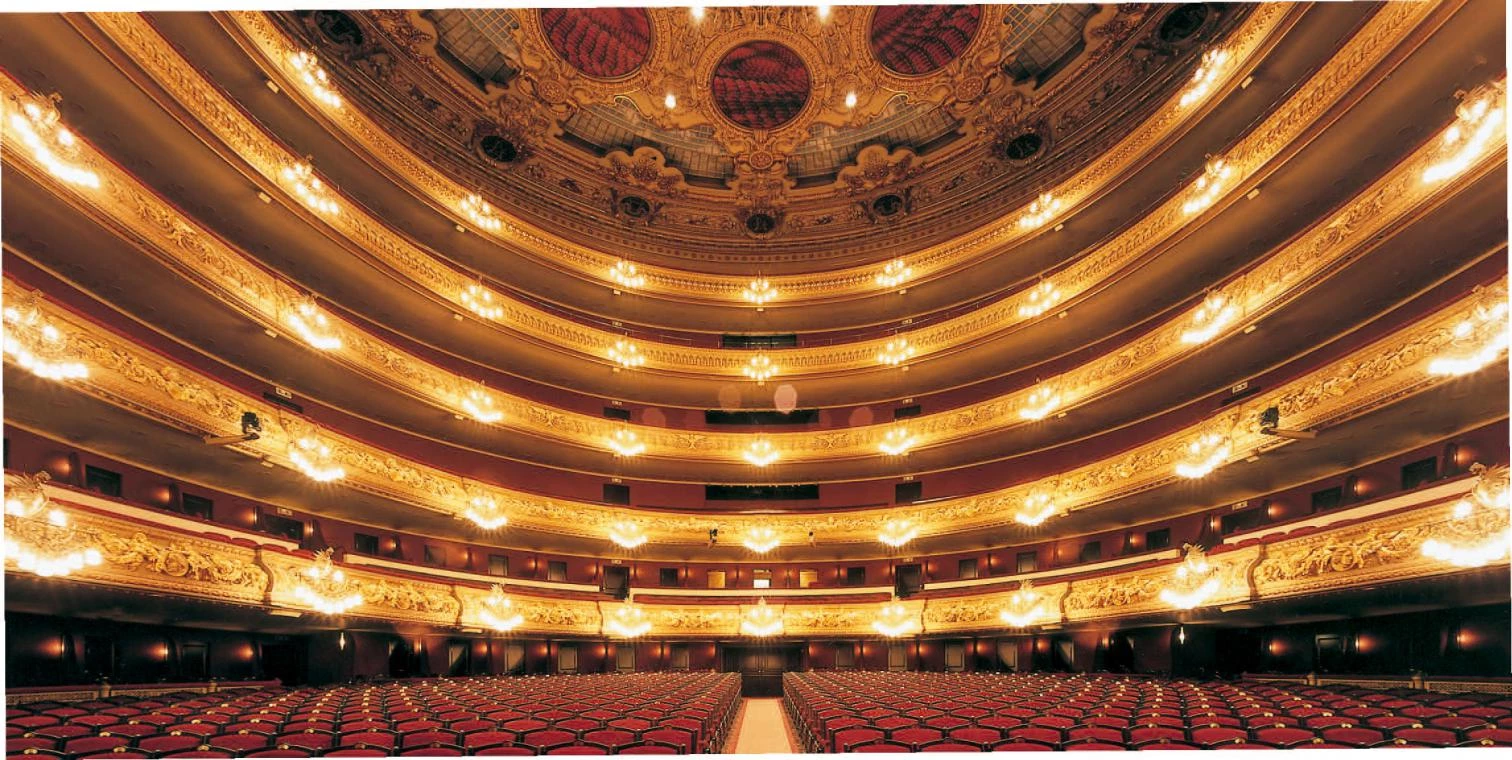

The splendid horseshoe of stage boxes in the rebuilt Liceo accurately duplicates the original decoration, with the addition of new oculi – by the conceptual artist Perejaume – that fake a calm swell of seating.